Back in the pre-COVID-19 days of intercontinental travel, traversing payment modes in the USA could feel like an eerily analogue experience for the European visitor.

Say you arrived in New York and chose to travel by taxi into Manhattan. You slip into the back of a yellow cab and arrive at your destination. You see the contactless sign on the card terminal in the back seat and get out your smartphone to pay using Touch ID. “Sorry,” the driver says. “It doesn’t work. You need to swipe.”

It’s a disgrace that America has been allowed to have such a slow payments system for so long

You wanted to ride the subway and had heard the city was installing contactless pads at the barriers, so you get your bank card out to tap. But the station you’ve arrived at hasn’t upgraded yet. You find yourself looking at an ancient metal machine that asks you to “dip” your credit card (good luck using a debit) and enter your zip code, which you don’t have. Welcome to New York and the US payments system.

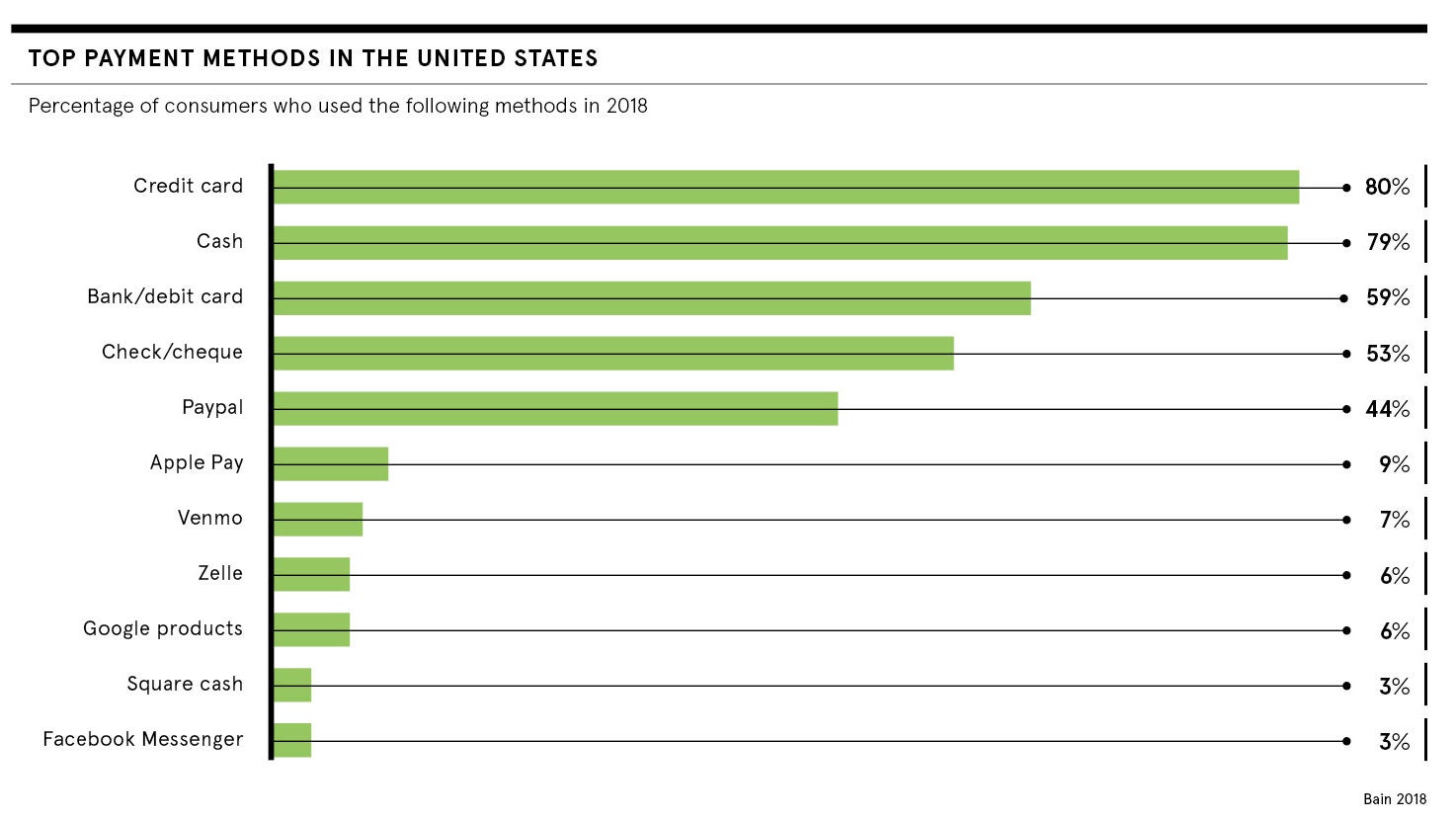

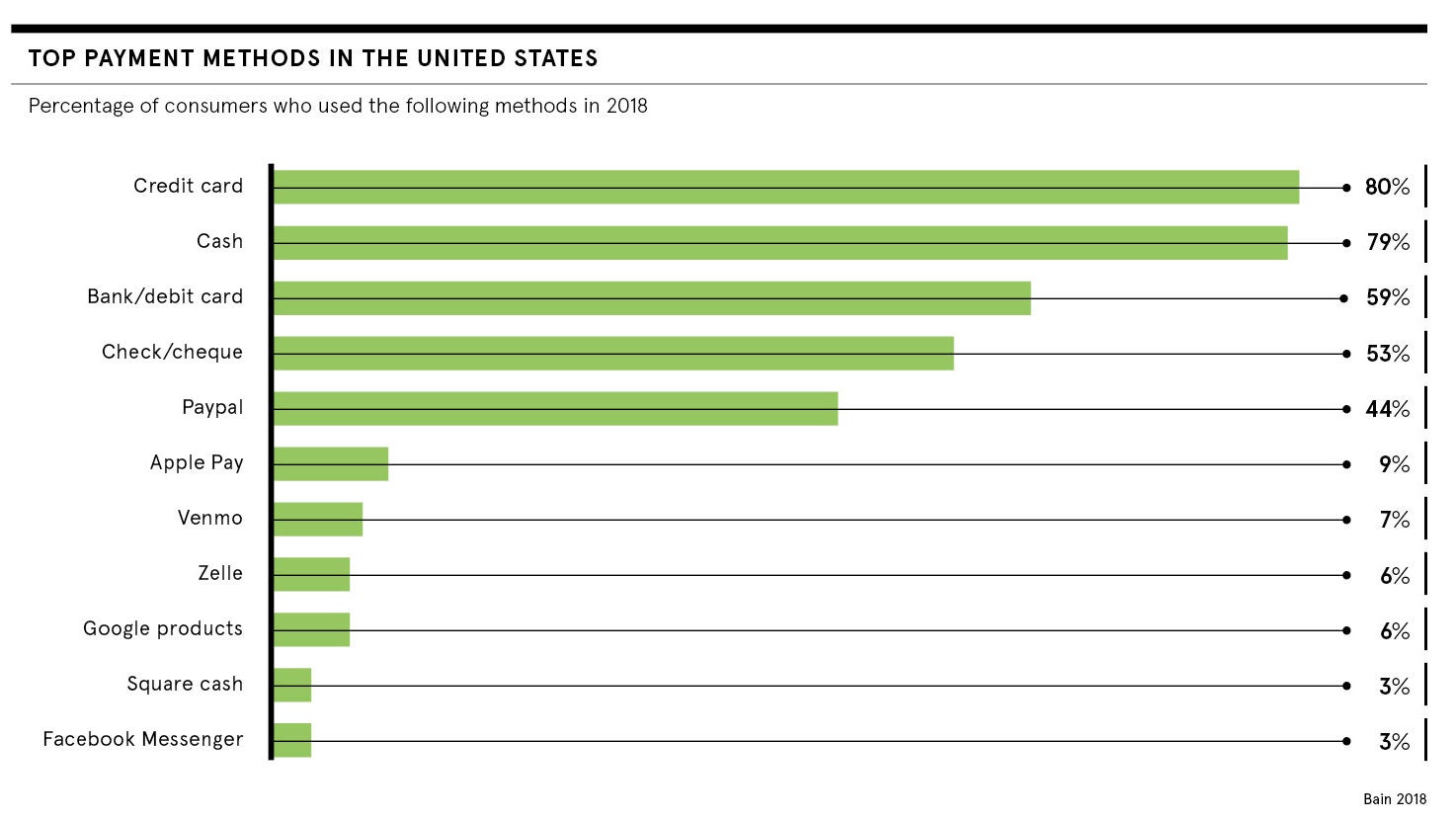

In a time when it’s possible to pay for something in China through facial recognition, payment modes in the USA feel clunky, even down to the process of signing for the bill in a restaurant and writing the tip on a slip of paper. Only 56 per cent of adult Americans made a mobile payment in 2018, compared with the 70 per cent who used a credit card and 78 per cent who used cash, according to the Pew Research Center. Why the hold-up?

Point of sale friction

Much of it comes down to consumer demand and the population’s consensus of what is “friction” when it comes to payment modes in the USA. The credit and debit card system has worked well in America for decades, unlike in societies such as India where the ease of mobile payments has quickly usurped centuries of trouble dealing in cash.

Pew’s research found a number of American consumers still have doubts over the security of payments on mobile. And for many, the system of whipping out your iPhone and getting it to recognise your fingerprint is burdensome in comparison to taking out your credit card and swiping.

Even writing a cheque, an act that feels somewhat antiquated in Europe, is not a pain point in a country where tips play a vital role in feeding the economy and social etiquette.

“Tips are relatively incompatible with most [European-style hospitality] set-ups because handheld terminals are so rare,” notes Tom Goodwin, head of futures and insight at Publicis Groupe. “I can’t see that changing in the future. For many companies, it would be a massive capital expenditure for what is deemed ‘fancy but not needed’ investment.”

Payment systems’ real slowdown

Beneath the visitors’ inconvenience lies a darker, more complex, underbelly of payment modes in the USA.

The actual speed at which funds are physically transferred between accounts runs at a much slower pace than the rest of the world, where real-time payments (RTP) are becoming ubiquitous across all continents.

“What the US has is an automated clearing house settlement process, which is designed for cheques,” explains John Heltman, reporter-at-large with American Banker. “These systems run on what’s called a batch process, where they literally take the cheques and run them like a load of laundry a couple of times a day.

“The advantage is it’s cheap for the bank. But it’s also slow: it takes a cheque three or four days to clear.”

For Americans with money, this is an annoying, but not insurmountable, part of life. But for those living paycheque to paycheque, it can cause major issues. The system is designed to clear the money coming out of an account before the money that’s coming into it, which means swathes of low-income Americans are plunged into overdrafts and charged fees, even though their net balance shouldn’t have put them in the red.

An updated RTP system would solve this problem. The technology is widely available and can be implemented at a federal level relatively easily.

It probably hasn’t, says Heltman, because it would give the larger banks with better resources too much power over the smaller ones. But for Brookings Institution economist Aaron Klein, the apathy towards moving to RTP comes from American banks’ financial reliance on overdrafts.

“If America had implemented RTP 12 years ago, when the Bank of England did, it would have put more than $100 billion into the pockets of the Americans living paycheque to paycheque, who end up going to payday lenders,” he says.

“It’s an engine of inequality and it’s a disgrace that America has been allowed to have such a slow payments system for so long.”

Point of sale friction

Payment systems’ real slowdown