With the proliferation of payment services since the financial crisis and a hitherto stranglehold on competition by the major banks, it’s no surprise the regulators have stepped in.

At present, gathering information to share with another party usually requires “screen scraping” of unstructured data and reformatting into structured data compatible with Excel or a database so it can be read.

But from January 13, 2018, the European Commission’s Revised Payment Services Directive (PSD2) will mandate all European Union member states, including the UK, and the European Economic Area to use open application programming interfaces (APIs), allowing financial transaction information to be shared with explicit permission from the account holder.

Its intentions are improved competition, cost-effectiveness and a more level playing field across the payments industry, while increasing customer protection. PSD2 serves to expand the reach of the first directive in 2009.

According to David Song, European developments manager at UK Finance, two main areas to be affected are payment initiation services, which reflect the market growth of e-commerce and mobile payments, and account information services, showing the growing trend towards consumers using multiple providers that increasingly need to talk to one another.

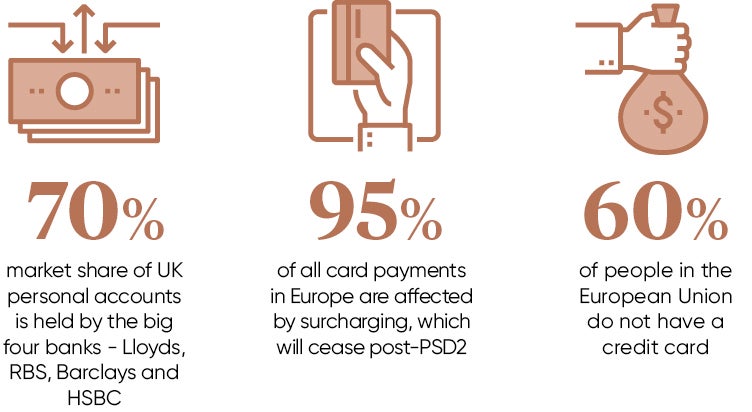

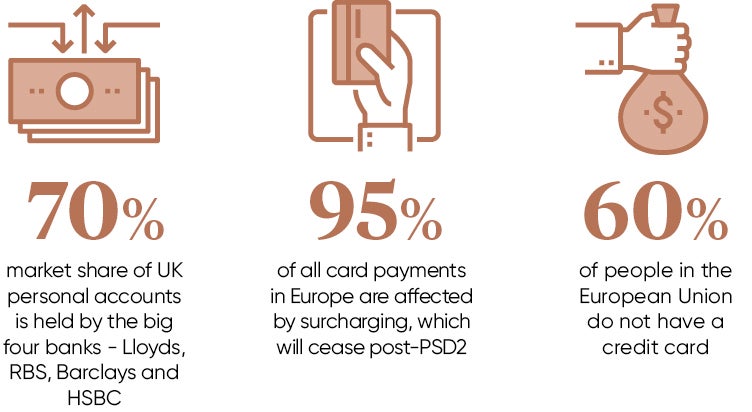

While in the UK card payments are fairly commonplace, the Continent is more inclined towards bank transfers. Around 60 per cent of the EU population does not have a credit card, according to the European Commission, and as such restrictions exist; many cards simply won’t work in other countries.

According to Experian, services such as iDEAL in the Netherlands, MobilePay in Denmark, Sofort in the wider EU and Pingit in the UK continue to drive down costs, especially for lower-value payments due to the lower overheads for merchants of being able to accept credit card payments. Gone are the days of Visa and Mastercard being the dominant twin schemes.

PSD2 also waves goodbye to card payment surcharging, affecting roughly 95 per cent of card payments in Europe, saving consumers approximately €730 million a year.

The big four banks, Lloyds, RBS, Barclays and HSBC, collectively accounting for more than 70 per cent of UK personal current accounts, and the stickiness of their assets, together losing less than 5 per cent of market share since 2005, gave the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) sufficient cause for concern.

Publishing its final report on the retail banking market last August, the CMA concluded: “Older and larger banks do not have to compete hard enough for customers’ business, and smaller and newer banks find it difficult to grow. This means that many people are paying more than they should and are not benefiting from new services.”

The report set “open banking” remedies such as standardised open API specifications, advance alerts and grace periods if account holders inadvertently went overdrawn, as well as monthly maximum charges and more transparent comparisons to encourage account switching.

So with little time to go before the January deadline, is the industry ready?

“It is a considerable endeavour and the timeframes are rightly ambitious,” says Esme Harwood, vice president of public policy at Barclays. “We feel confident we will be ready.”

API specifications were confirmed in July, putting the industry in a “good place” to hit the deadline, says Ms Harwood, but she warns that a lack of clarification of other PSD2 technical specifications may be cause for concern.

Ge Drossaert, chief commercial officer at challenger bank and fintech provider Fidor, says while tier-1 banks have the firepower to evolve into open banks, he expects to see more tier-2 banks partnering.

“We are seeing this in France and the Netherlands, in order to futureproof their businesses,” he says. “I see PSD2 as a trigger for co-operating with fintechs rather than seeing them as a threat.”

Across Europe there are “pockets of activity”, says Ms Harwood, such as the Berlin Group and various French organisations starting to point towards common standards.

It is a considerable endeavour and the timeframes are rightly ambitious

Yet she firmly believes the UK is blazing the global trail. “The US and Canada are looking to the UK as they develop their own approaches,” says Ms Harwood. “While the US banks have been using APIs for some time, the standardisation being developed across the UK is unparalleled.”

Mr Drossaert adds: “We have seen the National Payment Platform launching in Australia and recently the banking sector in Japan is being called on to pin their colours to a mast – are they open banks or not?”

As the use of third-party APIs is now standard in much of day-to-day life, from eBay in the retail space to Uber, which integrates with Google Maps’ API for location and PayPal’s API for payment, the use of open APIs for payments seems a no-brainer, yet not without risks.

According to the Open Data Institute, fraud currently costs the UK economy more than £570 million a year and it suggests that by pulling in data from multiple sources, third-party fraud detectors could aggregate data “to spot patterns that a single product provider wouldn’t see”.

Concerns also exist around excessive choice. Where consumers are used to dealing with a handful of payment providers, the sweeping changes bring other threats to light.

Guillaume Pousaz, chief executive and founder at payment provider Checkout.com, says: “Transparency over the number of legal entities that have access to sensitive financial data will cause the consumer a great deal of confusion.

“Keeping track of who has access to your financial data is going to be difficult as companies inevitably weave in terms and conditions without the consumers’ full understanding.”

This, in a world where absentmindedly clicking “I Agree” to unread Ts&Cs is the norm, swiftly becomes an area on which to keep a watchful eye.