One by one, the UK’s 600 defined benefit (DB) pension schemes have closed to new members, as employers struggle to contain their escalating costs.

The average life expectancy has risen by a decade since most of these private DB schemes were set up in the 1970s. Their collective liabilities, which exceed £2.1 trillion, stretch out decades into the future and have produced deficits that are a significant drag on corporate performance, curbing cash for expansion and acting as a barrier to takeover activity.

According to Mercer, the 350 largest listed companies were weighed down by combined deficits of £137 billion at the end of 2016, despite stock markets ending the year on a high.

To reduce the burden, companies are making eye-watering cash contributions into their schemes; last year £13.5 billion was paid in by FTSE 100 companies, brokers Jardine Lloyd Thompson has calculated.

Some pension scheme sponsors have been able to limit their risk by effecting buy-outs where the employer pays a fixed amount to an insurance company to absolve itself of any liabilities relating to some or all of its members, usually pensioners rather than deferred members, and the insurer delivers the cash flows required to pay the members’ benefits.

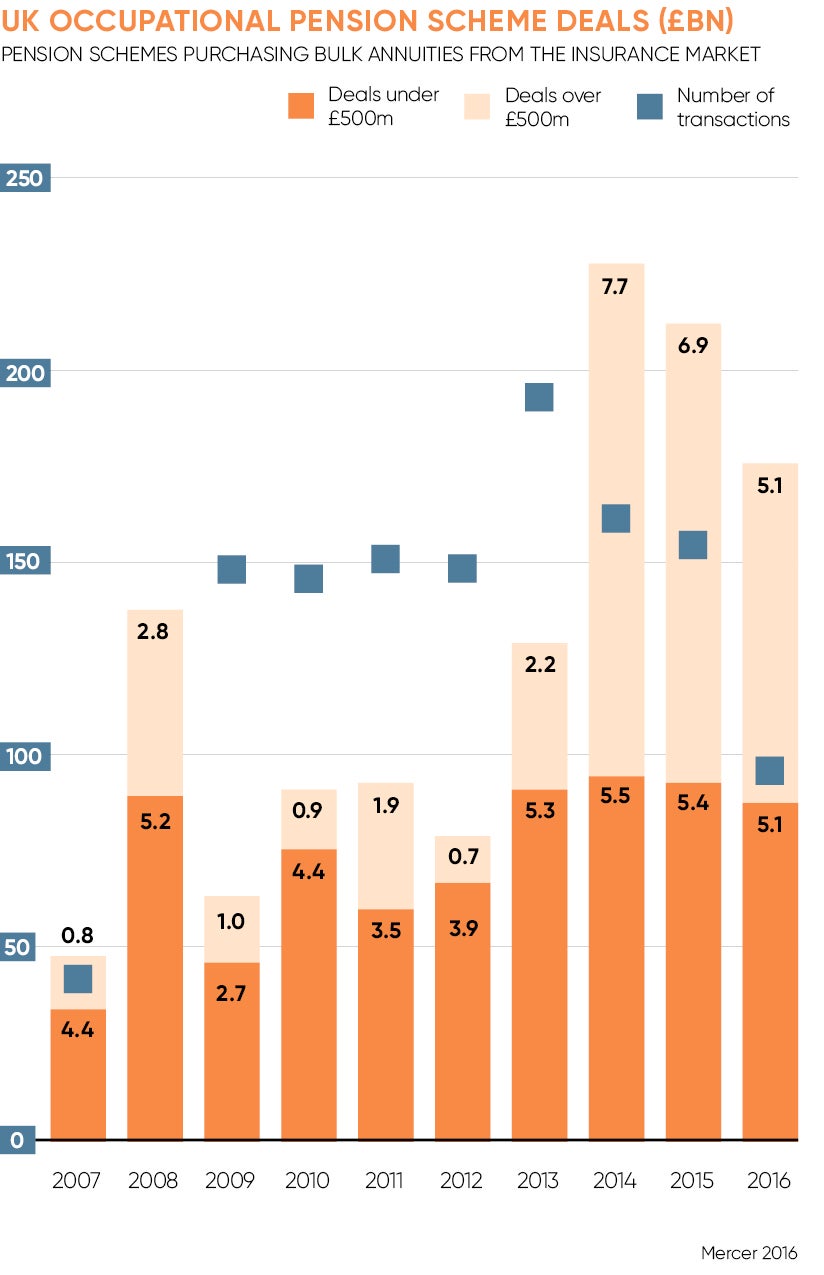

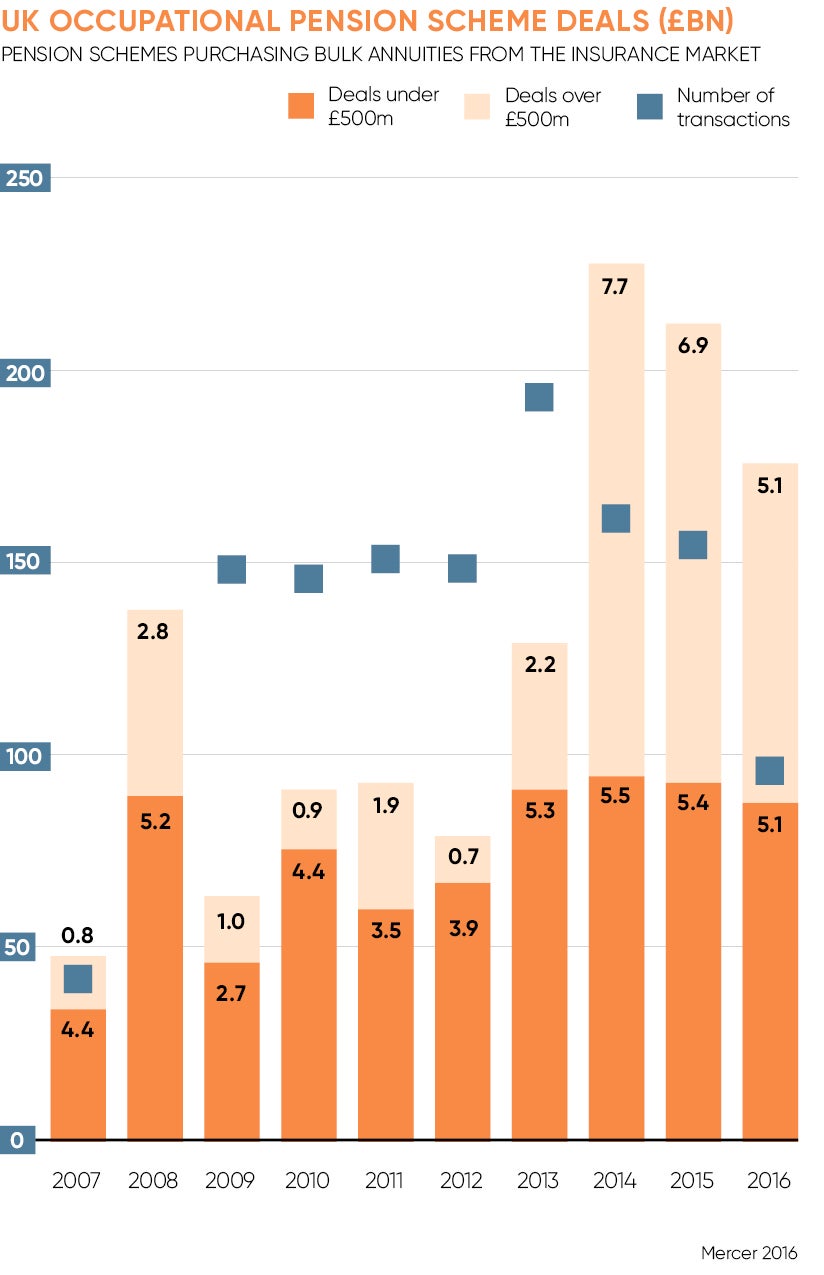

Last year more than £10 billion of these contracts were written in the UK. Consultants predict the total volume this year will hit a record level at around £15 billion. Such transactions are invariably greeted favourably by the markets.

Buy-ins and buy-outs

Buy-out activity includes full buy-outs, and also buy-ins and longevity swaps. A buy-in differs from a buy-out in that the pension scheme takes possession of the contract, so any money it can make on it benefits all members, not just those covered by the contract.

Some schemes are also putting in place longevity swaps, to reduce the risk of members living longer than expected. In this arrangement, the scheme makes regular payments based on agreed mortality assumptions to an insurer, which in turn pays out amounts based on the scheme’s actual mortality experience.

Very often the pension scheme will exchange a holding in gilts for a buy-in contract. Gilt yields are currently very low by historical standards so it makes sense for the insurer to hold longer-duration illiquid assets against the contract, making its profit on the illiquidity premium.

“Brexit has helped because long-dated debt-like illiquid assets such as infrastructure, commercial mortgages, equity release, ground rents and some commercial property are currently cheap, and so give a better return than holding gilts,” says Charlie Finch, a partner at Lane Clark & Peacock. “Risk adversity in the current economic climate has allowed insurers to pick up these assets more cheaply.”

Buy-ins often presage a full buy-out and increasingly pension trustees are setting up a number of buy-ins under an umbrella scheme, which allows contracts covering different member cohorts to be completed quickly when the timing is right.

Some pension scheme sponsors have been able to limit their risk by effecting buy-outs where the employer pays a fixed amount to an insurance company to absolve itself of any liabilities

Deals depend not only on the longevity of a specific tranche of members, but on the assets available to match the cohort’s liability profile, with insurers often asked to quote on several different subsets before the client selects the most cost-effective deal. For example, the ICI pension fund set up an umbrella contract in March 2014 and has since written 11 buy-ins covering £8.2 billion. It was this structure that allowed the scheme to transact a £750-million buy-in the week following Brexit at terms so favourable that it made a saving of £10 million.

Buy-outs and buy-ins have become possible in recent years because most schemes are closed to new entrants, so the life expectancy of scheme members is reducing, and this makes it surprisingly easier to estimate the remaining liabilities and how best to match them with investments.

Trustees have also reacted to funding volatility over the last ten to fifteen years by de-risking their assets, switching from risk-on assets such as equities to risk-off assets such as bonds and gilts, which are directly linked to the inflation and interest rates on which liabilities are calculated. With the value of scheme assets and liabilities reacting to these factors in the same way, funding level volatility can be reduced.

“The whole thing comes and goes in line with financial conditions,” explains David Ellis, UK leader for bulk pension insurance advisory at Mercer. “It depends on how much corporate cash is out there and the scale of the deficits. There has been swelling demand from UK corporates, some of it due to financial conditions and some because schemes have got themselves into a position where they are well hedged, have good cash flows and are looking at the future.”