The failure of the retailer BHS last year caused much anger among the public and considerable soul searching by the corporate world. Not only had a well-known name disappeared from the high street, but 11,000 people lost their jobs. According to a committee of MPs “a large proportion of those who have got rich or richer off the back of BHS are to blame” for the retailer’s failure.

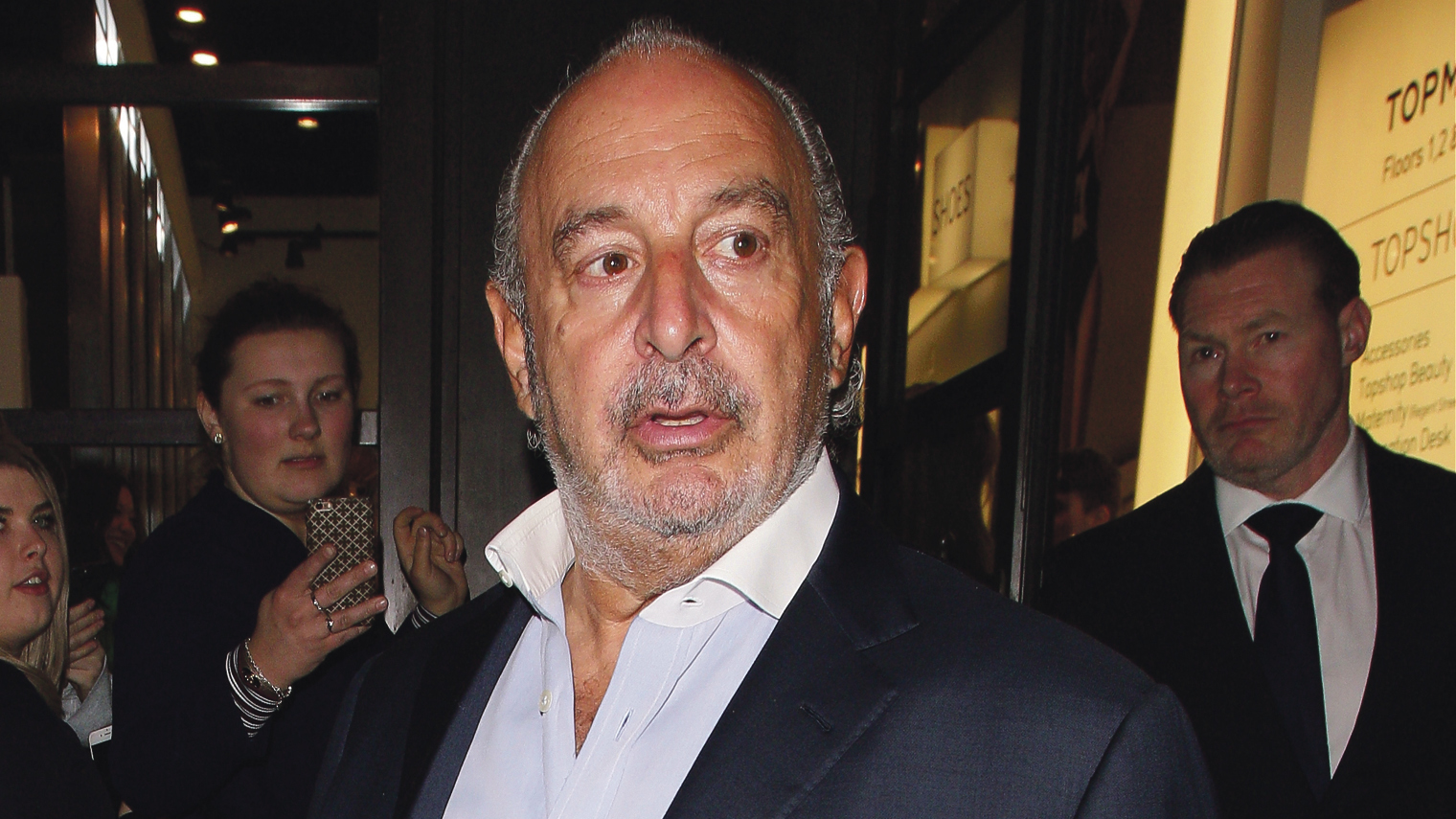

There was also controversy about the fate of the company’s pension scheme and its 19,000 members. MP Frank Field, the work and pensions committee chairman, was among those who demanded that Sir Philip Green, the former owner of the BHS group, donate around £600 million to the pension fund. In February Sir Philip handed over £363 million.

Increasing risk

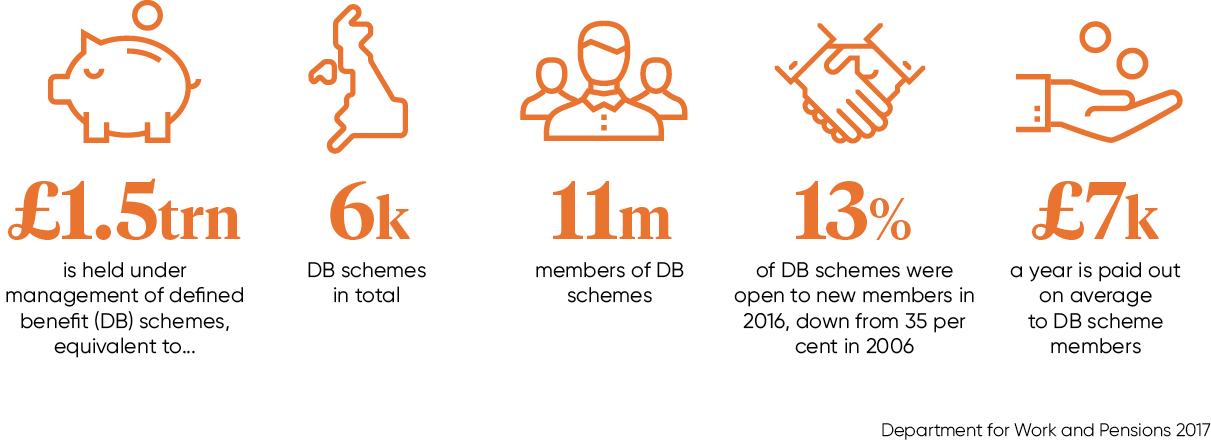

As more companies face a growing range of economic risks from disruptors, Brexit and an anti-business sentiment among other issues, protecting corporate defined benefit (DB) pension schemes is increasingly becoming a focus of attention.

“The real shock was that the business was sold as if the pension debt was not material,” says Baroness Dr Ros Altmann, former pensions minister and BHS campaigner. “With Philip Green standing behind it, the scheme didn’t look like an accident waiting to happen until he decided to sell the company.”

Nothing has yet been done to ensure this won’t happen again

Catherine McAllister, head of pensions at Addleshaw Goddard, London, says: “Although the numbers are eye watering because of the size of the scheme, personally I didn’t think it was a shock. Scheme funding has really suffered over the last nine years and many schemes have large deficits, which seem to keep getting bigger as market conditions have remained very difficult.”

It’s worth noting, of course, that there’s nothing that pensions legislation can do to stop a company from going bust and in fact a pension deficit can sometimes itself lead to insolvency. Ultimately, the Pension Protection Fund will ensure the majority of the pension that an individual has built up will be paid. But campaigners are still concerned and want to see greater protection for pension fund members in these situations.

“Nothing has yet been done to ensure this won’t happen again,” warns Lady Altmann. “The government needs to ensure that the regulator can demand more information. Trustees should also be able to resist employer refusal to discuss the employer covenant and the impact on security of member benefits resulting from a takeover or business sale.”

Sir Philip Green, former owner of BHS, handed over £363 million to the pension fund of the retailer

Learnings

However, Jon Hatchett, head of DB consulting at actuaries, pensions and investment consultants Hymans Robertson, believes the scandal has already changed the way in which company DB policies are viewed.

“The [BHS] case caught the public’s attention and so galvanised politicians,” he says. “In the difficult balance between investing in businesses and securing legacy pensions it has moved the dial several notches back towards security. This is at odds with where we were a few years ago when the ‘sustainable growth’ objective arrived for the Pensions Regulator.”

Chris Curry, director of the Pensions Policy Institute, believes the BHS case, along with the introduction of more freedom and consumer choice among pensions, has helped to make defined contribution (DC) pensions more attractive. “They’re ‘owned’ by the members rather than relying on the employer, even though they are usually less generous and place more risks on individuals,” he says.

In the long term, Mr Curry believes, the move from DB to DC pensions will reduce the reliance on scheme sponsors. “But in the short to medium term, the fact that many DB schemes are closed can mean there’s no new money coming in to the schemes other than from the employer and the contributions being made by the employer may be for past, rather than current, employees,” he says.

“This could weaken the employer’s attachment to the scheme, particularly if the contributions made to the closed DB scheme reduce the contribution that could be paid to current employees in a DC scheme.

Ms McAllister believes that the Pensions Regulator could offer more support to those trustees and companies looking to secure their DB pensions. “The Pensions Regulator has many powers, but its approach has very much been to provide information. They do lots of that, just have a look at their website and you’ll find large numbers of very long codes of practice and guidance notes. They need to be ‘a referee and not a player’. However, in the absence of regulator intervention, funding must be agreed between an employer and the trustees,” she says.

Mr Hatchett advises companies to ensure they can afford the risk they are running within their schemes and that they are taking no more risk than they need to pay the benefits. He says: “There are now a wide range of actions companies can take to ensure schemes are not only affordable today, but that they remain affordable in future.”