The global financial crisis sounded a wake-up call for financial services companies the world over. The crisis not only raised questions over the solvency and stability of financial behemoths, it also fired the starting gun on a tidal wave of regulation, designed to clean up bad practices and increase transparency of global systemic threats.

While regulators sought to shape the future behaviour of capital market participants, they also took swift action to punish the reckless and inconsiderate behaviour that led to the crisis, dolling out hundreds of billions in fines to those companies considered responsible. A 2017 Bloomberg report, citing data from Boston Consulting Group, calculated the total amount in global fines paid since 2008 at a staggering $321 billion.

It would be easy to assume such a vast cost would trigger quick reforms at the major corporations, and that these companies would be keen to change their systems, practices, suppliers and technologies away from those which led to such opacity. But the reaction was quite the opposite.

Capital markets should not be held back by fear

In fact, the speed of change in capital markets has been relatively slow, particularly when compared to other areas of financial services, such as retail banking, consumer lending and payments.

“Disruptors looking to enter capital markets face an enormously complex environment,” says Fiona Hamilton, vice president Europe and Asia for Volante Technologies. “Unlike, for instance, effecting wholesale payments, disruptors face a multi-asset, multi-dimensional and multi-faceted backdrop. Arguably it is a much harder process to find a disruptor that ‘suits’ all.”

Senior City figures agree that major players in capital markets have shown themselves to be exceptionally risk averse when it comes to trying new methods and the reason may surprise.

Many believe that much of this risk-averse behaviour has arisen from the heavy regulation of markets, the complexity of regulatory requirements and resulting fear of being fined.

Alistair Haynes, chief executive of London-based trading venue Aquis Exchange, also acknowledges the widespread fear, but goes even further, blaming naivety, misconceptions about costs and, most notably, business concerns about losing a competitive advantage if they split from the established way of doing things.

“It is all about fear. Fear of being caught doing something you shouldn’t, the fear of being fired, the fear of making a mistake. Of course, the world is changing so fast that this is completely the wrong attitude. There should be a fear of doing nothing.”

How regtech is making its way into capital markets

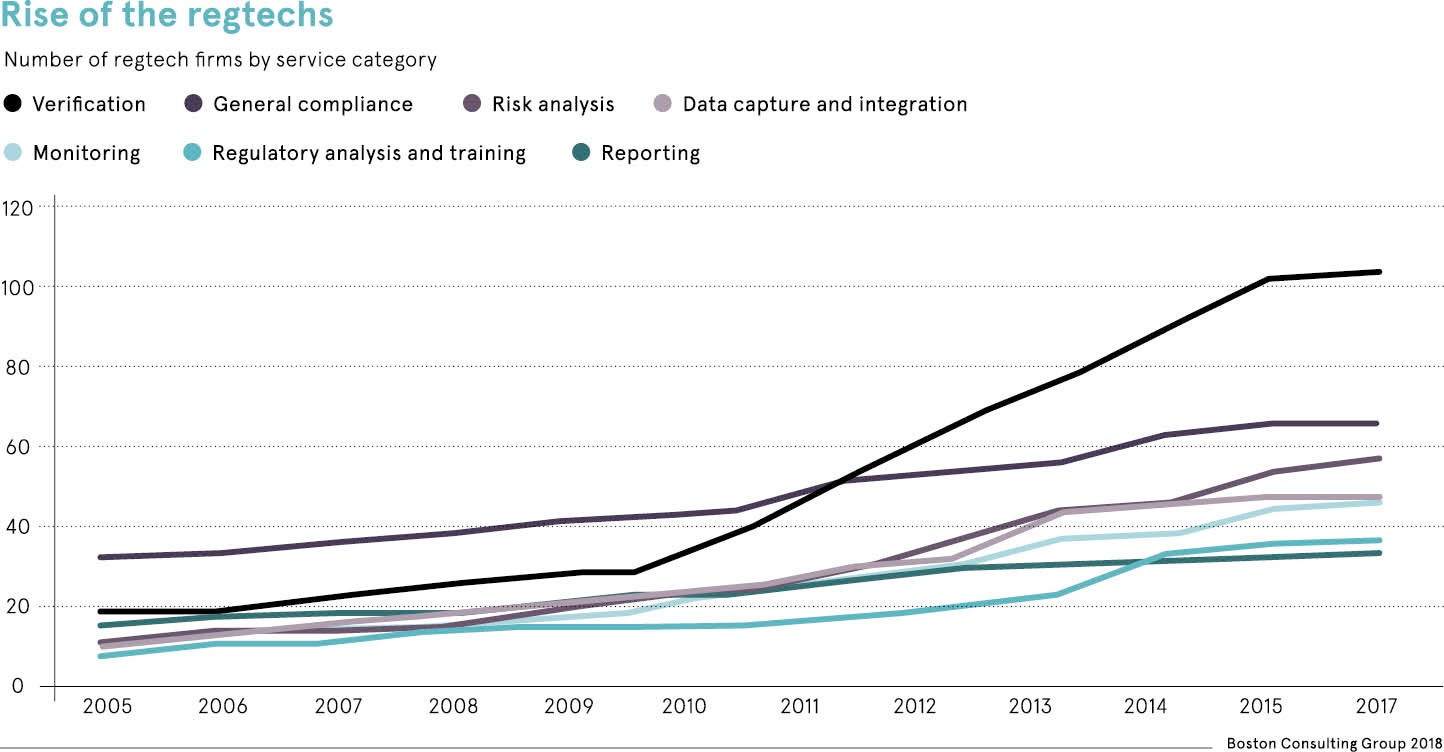

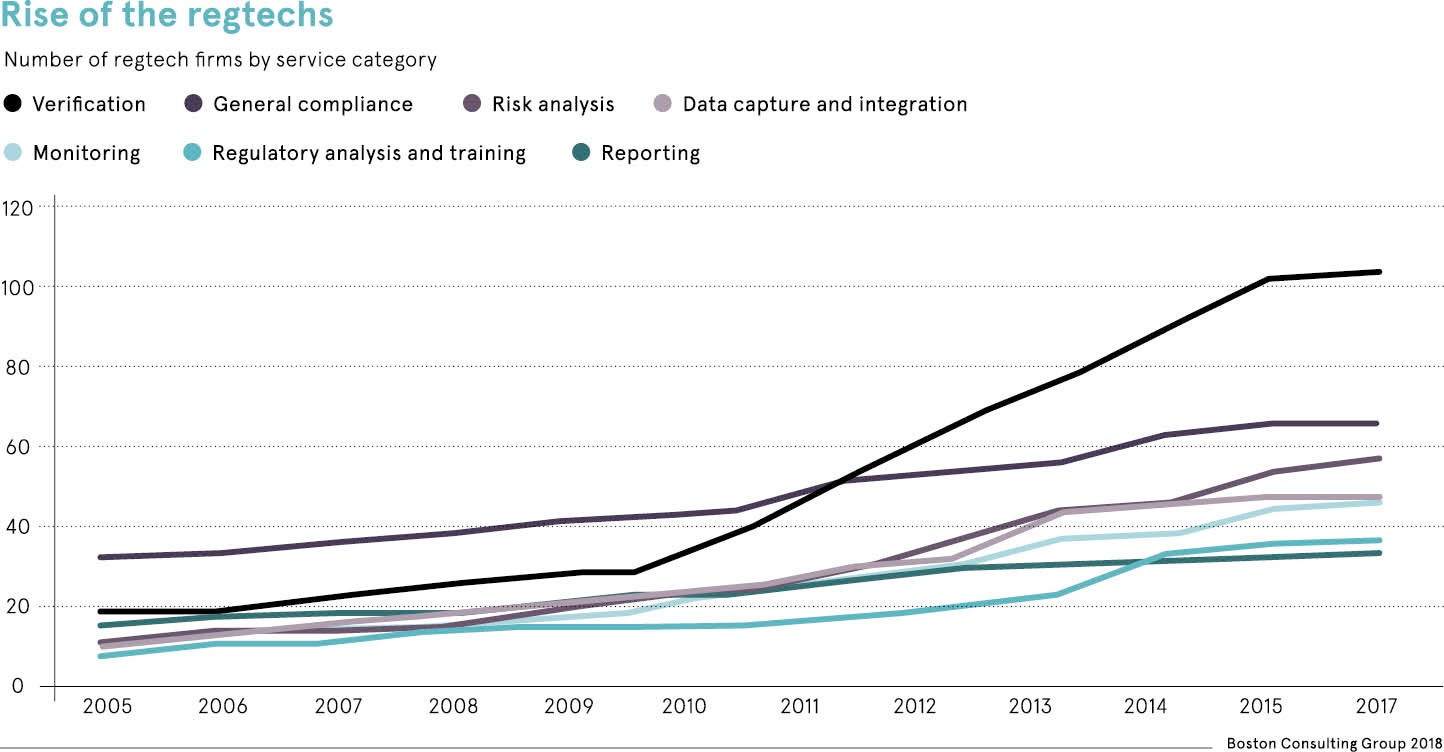

Despite this culture of fear, the past decade has seen a wave of new companies, emerging in response to the seemingly never-ending stacks of new regulation, that are specialists at assisting financial services firms with the regulatory burden through technology.

These so-called regtech businesses use advances in technology to improve corporate understanding of the risks to which they are exposed, improve compliance oversight and offer solutions to mitigate risks, and at a cost which they claim is lower than traditional methods.

RSRCHXchange is one of the myriad businesses to spring up since the crisis. It offers asset management firms a way to read, purchase, evaluate and monitor research services from banks, brokers and boutique providers, through its platform.

Regtech firms are nimble, run by experts in the field and can move quickly; effectively they enable financial institutions to outsource the innovation process

Like most other regtech businesses, RSRCHXchange has had to elbow its way into the capital markets community. Co-founder Vicky Sanders says capital markets is one of the toughest sectors to crack.

She explains: “It’s heavily regulated, has mission-critical functions, operates twenty to twenty-four hours a day six days a week, has networks of co-dependencies and is highly competitive. That makes it tough for any vendor.

“Scale is often a prerequisite for success, building a wide and deep moat. Disruptors need more than a proof of concept. To win new business, they require a live product and usually an existing pool of customers. That raises the cost to getting started compared with the other industries and presents the challenge how to win the first customer.”

Uptake for regtech has been slow, but it is taking off

The issue doesn’t stop there. Ms Sanders says regtech firms looking to get even a toehold in the sector know that driving growth while maintaining stability is a tricky business, so firms should expect sales cycles to be long.

Given that it can take a long time to secure that all-important account, new challengers also need to have the wherewithal to stay around long enough for the market to come their way.

But once a regtech company does achieve widespread recognition, it can have radical repercussions for corporate cost efficiency, transparency and speed of operation. It is no accident, then, that companies are beginning to spend big on regtech.

A Financial Times report in 2017 estimated that spending on regtech would reach $76 billion by 2022, up from $10.6 billion in 2017. A separate report from Juniper Research found that investors are also backing the regtech revolution, with $1.37 billion invested in regtech companies in the first half of 2018, more than in the whole of 2017.

Capital markets landscape becoming more amenable to new tech

Terence Chabe, a capital markets specialist at Colt, says regtech companies have several advantages over incumbents.

He explains: “Due to regulation and market conditions, a lot of banks are retrenching from non-core activities. They don’t have the internal expertise to develop these innovative solutions and internal processes mean any new technology projects are tightly controlled.

“Regtech firms, by contrast, are nimble, run by experts in the field – often ex-employees of the institutions themselves – and can move quickly; effectively they enable financial institutions to outsource the innovation process.”

While the challenges are very real for those actively making inroads into the market, there is a genuine belief that the capital markets landscape is finally starting to change, to become more accommodating to the new businesses offering alternative solutions to legacy approaches.

RSRCHXchange’s Ms Sanders believes things are changing for the better. She concludes: “Big regulatory changes come about once a decade in capital markets. Those changes create opportunities for regtech firms to implement technology to solve problems, old and new. They can innovate faster than incumbents and pivot when something isn’t working.”