The theory of disruptive innovation isn’t quite as controversial as the theory of intelligent design, but it’s getting pretty close. On the face of it, simple enough – unexpected innovations reach new customers and lower prices. The kick comes in the tail. Clayton Christensen, who pitched the theory back in 1995 in The Innovator’s Dilemma, argues that disruption is usually fatal and old-school incumbent companies either shrink or die. If it’s true, that’s bad news for banks.

“Finance is ripe for disruption,” according to Rachel Botsman, author of What’s Mine Is Yours: Collaborative Consumption Is Changing The Way We Live. “It fulfils all four of the key criteria: there are fees that can be cut out of the process and people will benefit; it’s unnecessarily complex; trust has broken down; and people who have been excluded from the system are getting new access. It’s where the media industry was five years ago or the music industry just as Napster hit.”

She has a point. Banking hasn’t really changed since the days people would send livestock to market and get a piece of paper in exchange, according to KPMG’s UK head of payments Mark Hale.

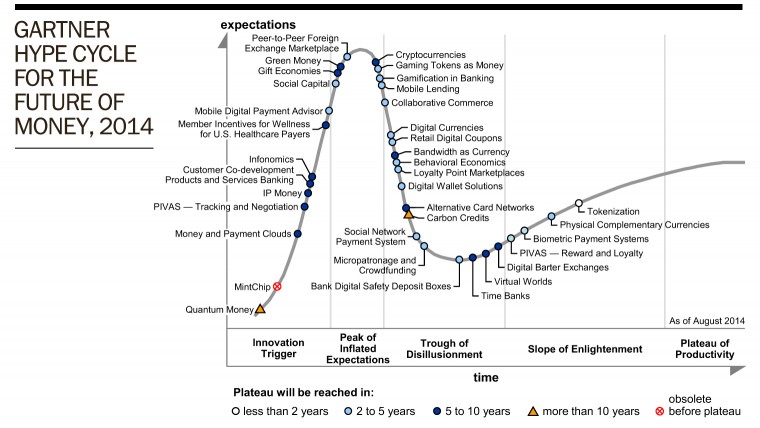

But 2014 was pretty much the year of disruptive innovation, from new online banks, such as Fidor, and the rise of the robo-investment adviser, including Wealthfront, Motif Investing and Betterment, using software to build portfolios in minutes at a fraction of the cost of a professional.

Then there was the spread of crowdfunding into the venture capital arena and a new form of child-focused pre-pay debit card, Osper, aimed at teaching kids sound budgeting, but inevitably eating away at banks options in recruiting future clients.

Ms Botsman’s four reasons – fees, complexity, trust and new access – hold good across the board.

UNDERCUTTING BANKS

“You’ve had that experience when you get your money at the airport and think, ‘I’m sure I haven’t got the best deal here’,” says Michael Laven, chief executive and co-founder of The Currency Cloud, a rapidly growing London-based startup undercutting banks on the currency exchanges. Founded by experienced foreign exchange traders and payments experts, its XBP Connect API platform shaves as much as two thirds off transaction fees for business clients, buying on the capital markets and disclosing its price to clients then charging a fixed fee.

Currency Cloud is business-to-business, but disruptive consumer currency startups, such as Azimo and Transferwise, are clients and pass savings on, according to Transferwise co-founder Taavet Hinrikus, who helped launch Skype.

“No telecom companies took Skype seriously at launch,” Mr Hinrikus points out. “But ten years later it handles 30 per cent of international calls.”

Complexity, meanwhile, has traditionally been the financial world’s defence against uneducated intruders, argues Philipp Moehring, head of all things Europe at Syndicates, launched last year by AngelList, a venture capital introduction site.

Complexity has traditionally been the financial world’s defence against uneducated intruders

Syndicates resembles the original investment clubs gathered in London coffee houses in the late-1600s. The site lets accredited investors co-invest with sophisticated angel investors who know how to pick a good deal. The venture capital community hasn’t welcomed him with open arms, Mr Moehring admits. “The VCs want to have their own proprietary info because they don’t want anyone else to see where they are investing. Our philosophy is that there is no proprietary information anymore, there is no black box. That’s how it works these days. Welcome to the new age of investment,” he says.

As for trust? “You might expect consumers to trust long-standing brands such as banks when it comes to new technology like m-commerce,” says Aunkur Arya, general manager mobile at mobile payments processor Braintree, which handles payments for Rovio, Airbnb and Uber. “But really it has been startup merchants introducing the consumer and building trust.”

There’s a reason for this, argues Trustev chief executive Pat Phelan. “There is essentially no exact determination that you are who you say you are on mobile, because your handset doesn’t have an IP address,” he explains. Cork-based Trustev looks at 280 different data points in every mobile transaction, including biometrics, typing speed and location, to build up a “digital fingerprint”. His target? Verified by Visa.

Founder of Osper, former maths teacher and ex-Spotify executive Alick Varma, is less aggressive. He secured £6 million in funding in June and is currently rolling out his shiny pre-paid orange debit card, aimed at eight to eighteen year olds, across the UK. But his stated aim is encouraging young people to save money. “Kids aren’t saving, they don’t understand how to budget and one in five eight to eleven year olds use their parents’ credit cards without permission,” he says.

SNAPPING UP CUSTOMERS

Osper’s app is downloaded to parents’ and kids’ phones, allowing everyone to keep an eye on spending. By undercutting bank debit cards on age – banks issue to 11 year olds – he’s snapping up consumers earlier than his rivals.

Under conventional disruptive innovation theory, incumbents struggle in the face of nimble newbies, like woolly mammoths lumbering to their doom in a shower of tiny arrows launched by marauding hunter gatherers. But there’s some evidence to suggest this isn’t necessarily what will happen in finance. Some startups, such as London-based PayLiquid, have been launched specifically to help finance companies adapt. Chief executive and founder Sanjay Sondhi has built a mobile-first order-to-cash cloud-based sales solution that back Barclaycard Anywhere, which allows startups, trades people and small businesses to take card payments on their smartphone.

And there are signs that banks are catching on. Research by New City Agenda, a think-tank, claims Britain’s largest banks will take a generation to change their cultures. But Barclays’ recently launched fintech accelerator programme has already seen its first startups emerge and Lloyds is backing a “startupbootcamp” scheme, suggesting innovation culture is spreading within some banks.

“Anthony Jenkins [Barclays chief executive] has been pushing the bank to embrace the technological revolution,” says Darren Foulds, Barclays managing director, mobile banking and Pingit. “Three years ago we had no native apps. Typically change programmes take two-and-a-half years to push through, but we produced Pingit in seven months.”

Launched in 2012, by 2014 it handled £609 million in payments and one homebuyer used it to pay a £23,000 deposit. The bank now updates its mobile app every six weeks. “Our customers check their mobile app 26 times a month compared with six times a month for phone banking and going into branches twice a month,” says Mr Foulds.

Is it enough to keep Clayton Christensen happy? Maybe it doesn’t matter. Disruptive innovation is currently facing serious academic challenges in the United States, led by Harvard’s Professor Jill Lepore, who questions whether the theory has been oversold. Looks like someone’s disrupting the disruptors.