The tax affairs of large international firms and wealthy individuals have become headline news in recent years. The ways they reduce their tax bills and how much tax they pay have moved from being largely private affairs into the public domain.

The tax affairs of large international firms and wealthy individuals have become headline news in recent years. The ways they reduce their tax bills and how much tax they pay have moved from being largely private affairs into the public domain.

Google, Starbucks, Amazon, high-profile pop stars, sports personalities and more have had their tax structuring plans, and the amount of tax they pay, splashed on the front pages. Their tax avoidance schemes have sparked much comment and questioning of the moral standing of such actions.

Perhaps the most controversial story was the so-called Panama Papers. More than 11 million confidential documents from Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca were leaked, putting the role of Panama in aiding wealthy individuals avoid tax in the spotlight.

The government’s role

However, there was less focus on the role the UK, its Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories played. More than half of the 300,000 companies that were clients of the law firm were registered in British-administrated jurisdictions.

The data revealed that of the 14,000 intermediaries Mossack Fonseca worked on behalf of, the UK was the second highest jurisdiction. The law firm worked on behalf of 1,924 UK banks, law firms, company incorporators and others to set up companies, trust and foundations for clients. The only jurisdiction above the UK was Hong Kong, which was under British control until 1997, and the data stretches back to 1977. Mossack Fonseca acted for 2,212 intermediaries there.

As well as having the most intermediaries, Hong Kong was also the most active jurisdiction with 37,675 incorporations on its behalf. The UK was third with 32,682. Switzerland took second place with 34,301. Also in the top ten was one Crown Dependency. The Isle of Man was responsible for 5,058 incorporations and took eighth place, despite not featuring in the top ten for the number of intermediaries using Mossack Fonseca.

When it comes to the most popular offshore jurisdictions as destinations to set up structures, those with links to the UK feature prominently again. British Virgin Islands, an overseas territory, was by far the most popular with 113,648 structures. This is more than double the 48,360 in second place Panama. Also in the top ten is British Anguilla, another overseas territory, with 3,253 in seventh place. Hong Kong was home to 452 structures and the UK 148.

It is therefore, perhaps, understandable there is a national debate on tax evasion and tax avoidance, especially in an era of high, and growing, levels of inequality.

There is the view that wealthy individuals are able to structure their financial affairs in such a way as to avoid large amounts of tax, while the less well-off do not have such options open to them.

Changing attitude to tax

Private client professions say that in recent years this environment has changed wealthy clients’ attitude towards tax. Not long ago, many were seeking advice on how to reduce their tax bill by as much as possible. Any legal means, no matter how aggressive, would have been considered and tax planning was a key driver of how they structured their affairs.

More recently, however, clients are seeking professional advice to ensure they are compliant. They want to adhere not just to the letter of the law, but to its spirit. Succession planning or asset protection now take the front seat and any tax benefit is of secondary concern.

Some of this is undoubtedly driven by the fear of being the next individual to appear on the front pages, but advisers say the appetite for the more aggressive forms of tax planning have waned.

There is also more of a consensus in political rhetoric around this issue. Parties from across the political spectrum have attacked tax avoidance. Successive UK chancellors have pledged a crackdown with a range of policies and legislation to this end.

However, there are questions as to how effective these moves have been. Perhaps given the widespread public perception on the issues, it also important how effective these moves are perceived to be.

It is understandable there is a national debate on tax evasion and tax avoidance, especially in an era of high, and growing, levels of inequality

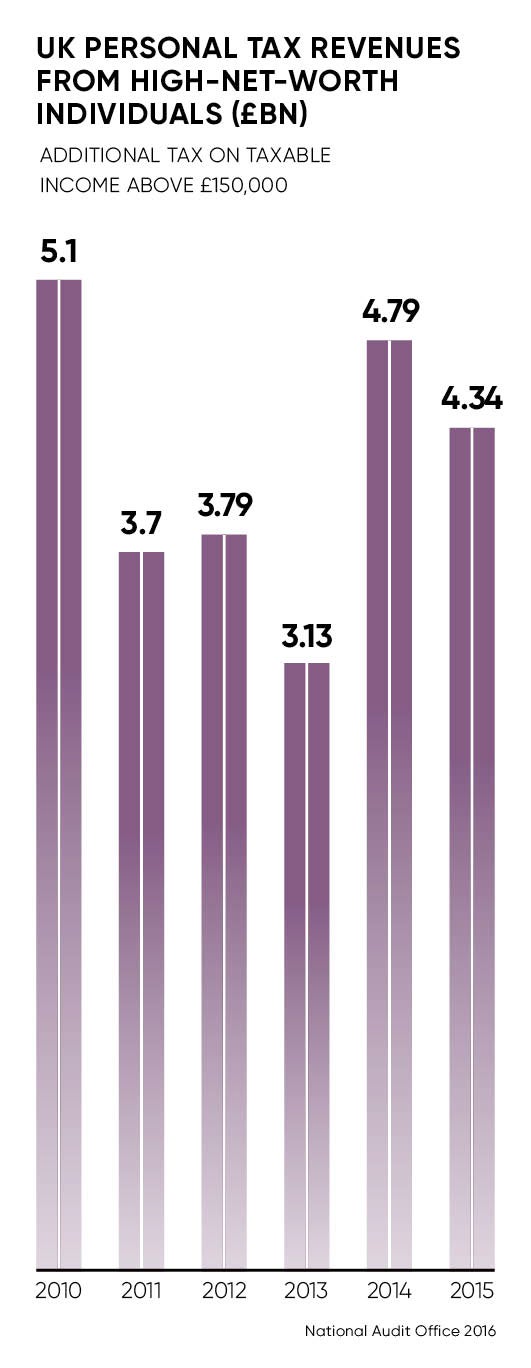

In January, a report from MPs on the Public Accounts Committee criticised work by HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC) to collect tax from wealthy individuals and raised concerns over the specialist high-net-worth unit that was set up in 2009. The MPs said the amount of tax paid by these individuals has fallen by £1 billion since the unit was established. “At the same time, income tax paid by everyone else has risen by £23 billion,” according to Meg Hillier, chairwoman of the committee.

HMRC was quick to defend itself against the report saying it had secured an additional £2.5 billion from the very wealthiest since 2010. “The vast majority of people in the UK pay all the tax they owe and today the top 1 per cent of earners pay more than quarter of all income tax,” HMRC said in a statement.

Whatever, HMRC has done there is one perception that politicians and the media have all helped to reinforce with their comments. In the current public debate the terms “tax avoidance” and “tax evasion” have become largely interchangeable and the distinction blurred.

There is, of course, one very simple difference between the two concepts. Tax avoidance is legal and tax evasion is illegal. Tax evasion is illegally hiding money from the taxman, while tax avoidance is using structures and managing your affairs to minimise the tax you are liable for.

If the government and other politicians really want to crack down on tax avoidance, they have the means in their hands. Through constant change and amendments, the UK has one of the most complicated tax systems in the world. Grey areas have been created and it is in these grey areas that much of the less accepted tax avoidance takes place.