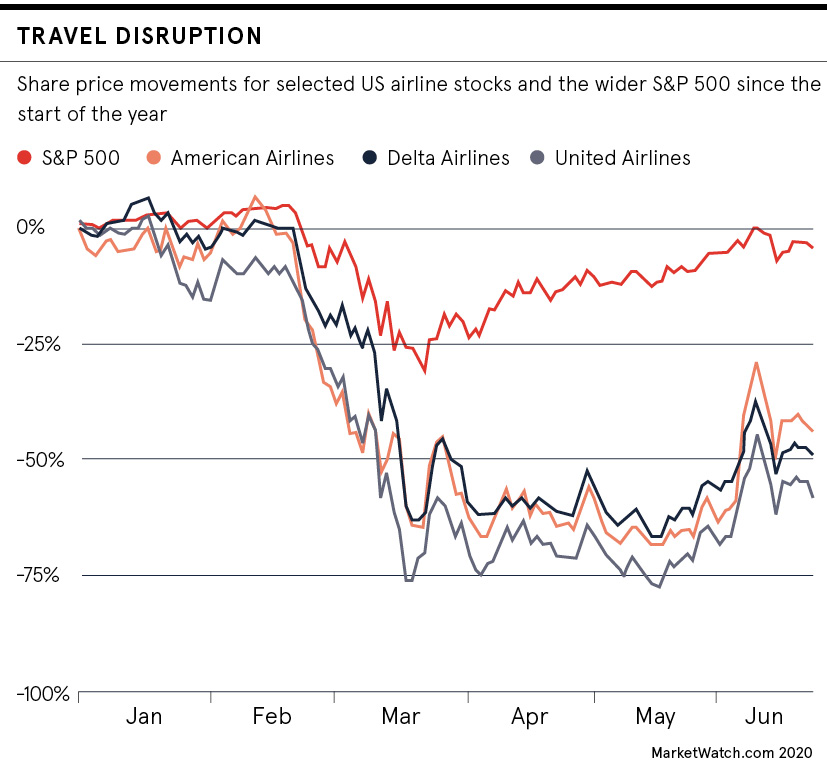

In early-May legendary investor Warren Buffett dumped his entire holding of US airline stocks, booking significant losses and claiming “the world has changed”. Air passenger numbers had been growing by 5 per cent a year before the coronavirus pandemic, but here was the Sage of Omaha backing out of “business as usual”. Was this a taste of the new normal for COVID-19 and the stock market?

Not every analyst agreed with Buffett. Governments wouldn’t let airlines fail, they said. Airline stocks had enjoyed an extended bounce after previous financial crises. The hope that history would repeat itself tempted some investors to leap on the shares Buffett unloaded. After all, the worst thing any investor can do is panic, whatever the extremes of short-term price fluctuations.

Who will be proved right? The problem for the average stock trader is that everything from March onwards is guesswork. Nobody has experienced a problem like COVID-19. Jeremy Cheah, associate professor of cryptofinance and digital investment at Nottingham Business School, thinks Buffett probably called it right.

“Until and unless there is massive restructuring in the airlines industry, it might make a lot of sense to give airline stocks a miss,” he says. “However, the decline is just the tip of the iceberg and symptomatic of what is happening in the wider economy.”

Coronavirus and the stock market: an uncertain recovery

Indeed, who would want a portfolio packed with airline, hospitality or travel stocks now? Rupert Thompson, chief investment officer at Kingswood Group, believes that the bricks-and-mortar retail sector is more vulnerable still. “The travel and hospitality sectors have been devastated by COVID-19, but unlike retail they were not in structural decline before and their long-term prognosis depends on whether a vaccine is found.”

Which is the fundamental question regarding COVID-19 and the stock market. When might medicine bring normality back? And how can stock trading happen with any degree of confidence when the long-term health of the global economy rests on something which could happen in six, twelve or twenty-four months’ time, or not at all? Without people being willing to work, travel and consume without fear, the economic recovery from COVID-19 could be “L” or “U” shaped, rather than the hoped for “V” graph.

Cheah says: “With low aggregate demand and both monetary and fiscal policies maxed out, there is very little hope, I’m afraid, for a return in consumer confidence. So, most stocks have been reset to reflect their intrinsic value in the new normal.”

Coronavirus crisis changes everything

And however the recovery pans out, many experts believe the stock trading landscape has changed for good. Investment strategies must take into account not just the obvious winners and losers from the pandemic, but also the changed reality of global business. Regardless of the shape of the recovery, there may be no going back.

“At least some of the changes in consumer needs and behaviour seen during the pandemic will carry over,” says Lutfey Siddiqi, visiting professor in practice at London School of Economics’ foreign policy think tank LSE IDEAS. “Social distancing has accelerated the need for digital transformation and de-globalisation has challenged the value of hyper-efficient, super-optimised supply chains.”

This is a significant point. Beyond obvious conclusions regarding COVID-19 and the stock market, one outcome could see markets favouring sectors and businesses that prioritise being resilient over being lean. As professor Siddiqi says: “Cost-cutting is no longer an unequivocal indicator of returns; it may actually signal increased risk and reduced resilience.”

Thompson agrees that anything but a vaccine-powered V-shaped recovery may have a profound impact on the stock market. And if a vaccine isn’t found soon? “Aside from the impact on sectors such as leisure and travel, it should lead to a more general focus on balance-sheet strength and supply-chain resilience rather than maximum operational efficiency,” he says.

Looking to the long term

That sentiment may provide the foundation for post-lockdown trading strategies. If the old certainties are over, it’s time for investors to build new narratives. Siddiqi says they might be around sectors like health technology or trends in behaviour, such as remote working or food technology. They should really include evidence of agility in the culture of a company.

“I would invest in an organisation that has a track record of responding and adapting to changes,” he says.

Richard Flax, chief investment officer at Moneyfarm, says debt levels are also important. “With relatively high levels of corporate leverage, fairly small shifts in consumption patterns could have a significant impact on the corporate landscape,” he points out.

The unchartered waters of COVID-19 and the stock market don’t end there. Bear markets are traditionally seen as the best time for canny traders, who make profit from others’ panic. But the pandemic has made the task more complex, if not impossible.

Thompson says that while the bear market should have been a dream for a market-timer or stock trader, sheer uncertainty means this bear has been as much an opportunity to “get whip-sawed” as to make money.

In that, as in so much else, COVID-19 has turned traditional stock trading wisdom upside down. Nuggets in the dirt are nowhere to be found, while the certainties that surrounded the longest bull market in history have been overturned in weeks. New trading strategies will be needed for the new normal. In the meantime, some fundamentals do still apply, says Marc Beattie, co-founder and chief operating officer at Arlo Wealth.

“Rule one for any investment strategy has always been, and always will be, don’t panic. Investors should plot their course through the market, ensure they are well diversified across asset classes, industries and locations, and maintain a long-term view. COVID-19 does not fundamentally change this,” he concludes.