Employing more than 60,000 people, the fintech sector in the UK now generates almost £7 billion a year, according to chancellor Philip Hammond.

In fact, Mr Hammond says the UK tech sector already contributes a bigger proportion of our GDP than any other country in the G20.

The government is stimulating growth with up to £1 billion increased leverage from the British Business Bank. But this increased spending was announced only after the European Investment Fund, which had pumped £2 billion into UK firms, slowed its activity in the UK.

However, a Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) investment awards scheme proposes a series of initiatives, worth around £750 million, which Mr Hammond hopes will boost competition in the UK business banking market and stimulate further investment in fintech.

I think there is certainly a potential risk that institutions hold back on making big investments into technology until they know what the rules will be

Banks typically operate across multiple markets and, consequently, service providers also need to work across borders. According to MEP Kay Swinburne, allowing cross-border mergers and acquisitions between fintech firms is necessary to support them. “Sometimes, organic growth is not enough,” she says.

A nuanced understanding of the fintech business is needed to assess the prospects for the industry. There are two major dynamics which determine the success of technology startups in any sector.

The first is access to the funding necessary to bring a big idea to market and support it until it can start generating revenue. The second is the legal and political environment in which they operate, limiting competitive forces and preventing regulatory barriers to engagement in the emergent industry.

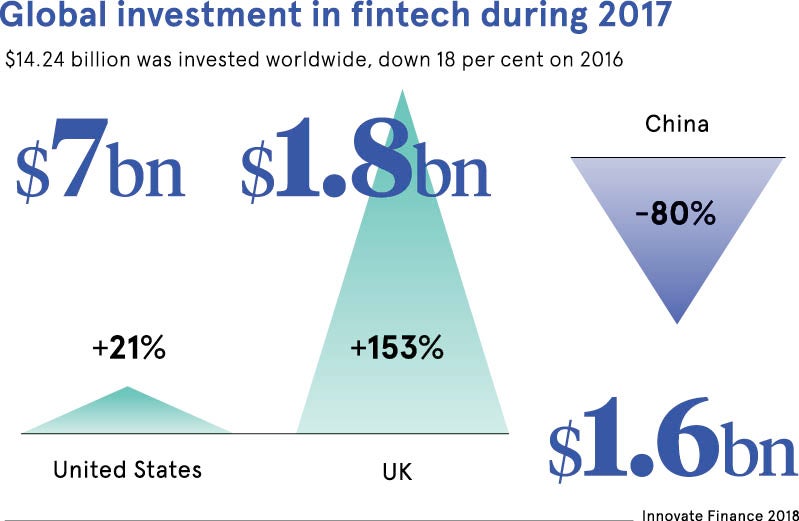

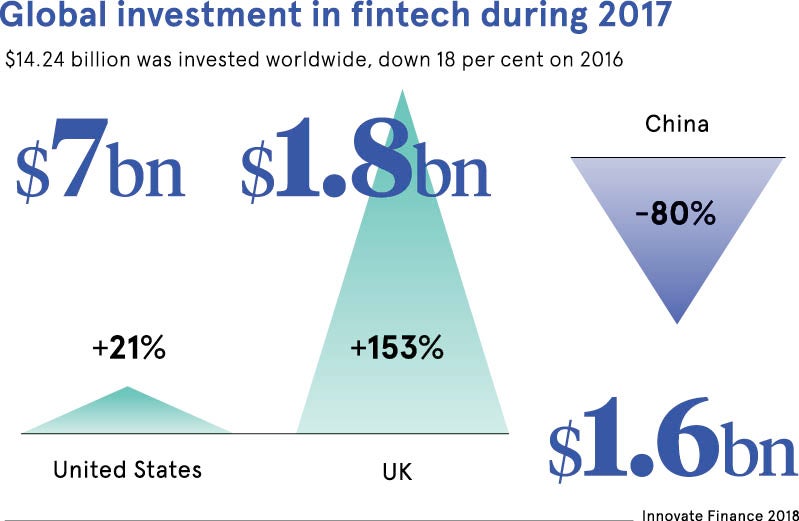

For fintech startups, there has been a boost in UK funding growth, according to research firm Expand, up around 137 per cent in the UK from 2014, compared with 110 per cent globally over the same period. “This is partly driven by the emergence of open banking and driven by the second payment services directive (PSD2), leading to the emergence of many digital banks that take many of the top spots in UK fintech league tables,” Expand says.

PSD2, which came into effect in January, has forced banks to offer a standardised connection to third-party technology and allow third parties access to customer account and transaction data if the customer has given permission. As a result, the firms can operate services on top of the banks offerings. It is a good example of the effect that regulation can have upon the operating environment.

So far, firms in this sector have appeared to benefit. One digital bank, Mayfair-based OakNorth, which specialises in lending to small and medium-sized enterprises, reported a profit of £10.6 million in 2017 and received the second-highest level of investment, totalling £143 million, among UK-based fintech firms, according to a report by private equity analyst firm Pitchbook and Innovate Finance.

Foreign exchange firms received the second largest proportions of investment (21 per cent) with Transferwise, receiving the greatest single investment of £197 million that year. Both Transferwise and OakNorth were in the top ten of largest deals globally in 2017.

Undoubtedly, there is opportunity here. Less than six months in, it’s too early to tell the effectiveness of PSD2 at increasing competition. However, this pan-European regulation opens finance up for fintechs to support banks beyond the local level.

Across the Atlantic, US firms have historically had this as a key advantage, being able to scale across a large home market where European firms have been constrained at expansion due to changing regulations across borders.

Philippe Morel, senior partner and managing director for London at Boston Consulting Group, says: “Regulatory harmonisation is very important because it affects the way that a fintech is allowed to collaborate with banks, the way they can use a bank’s data, the way they can use infrastructure such as cloud technology.”

The European Commission has made its first steps towards harmonising the rules across Europe through the Fintech Action Plan it announced on March 26. While it is still in the exploratory phases of developing a firmer regulatory framework, the plan has set the groundwork for national competent authorities to assess barriers to entry, impediments to growth and issues that will need to be resolved to support banking and the capital markets union in the European Union. The question mark that hangs over the UK is how it will operate post-Brexit.

“London will continue to be an attractive place to do business,” says Matt Hodgson, chief executive of fintech Mosaic Smart Data. “That said, the sooner the market knows what the regulatory environment will be, the earlier it can prepare. I think there is certainly a potential risk that institutions hold back on making big investments into technology and other significant changes until they know what the rules will be. That isn’t good for institutions or fintech companies looking to help them improve their operations.”