This year is set to be big for the lucrative defined benefit pension derisking market. The size of pension buy-in and buy-out deals, which insure schemes against future risks, has grown from £1 billion insured assets a year in 2006 to around £12 billion today, according to consultants Lane Clark & Peacock (LCP). Meanwhile, insurers report a deal pipeline worth £30 billion.

Demand for these arrangements is increasing as more employers look to remove the risk of future pension liabilities from their balance sheets. The biggest risk is stock market volatility, as large swings in the value of pension scheme investments can play havoc with companies’ finances, sometimes even causing or contributing to their collapse. Another is longevity as people living longer than expected can cost companies millions more in meeting their pension promises.

LCP says buy-out affordability has risen to its highest level since the 2008 financial crisis, due to three factors. Increasing competition among insurers has brought prices down and promoted innovation. A deceleration in longevity rates has meant insurers can charge companies less to take on the risk of people living longer. Thirdly, improving stock markets have boosted scheme funding positions – how much money they have compared to their liabilities – thus reducing the risk to insurers of taking them on.

In a buy-out, a pension scheme pays an insurer to take responsibility for paying the pensions of the scheme’s insured members. A buy-in is similar except the insurer makes payments to the scheme, which then pays the members. It is usually a step towards full buy-out and winding down of the scheme. Another derisking tool is a longevity swap, which transfers the risk of pensioners living longer than expected to an investment bank or insurer.

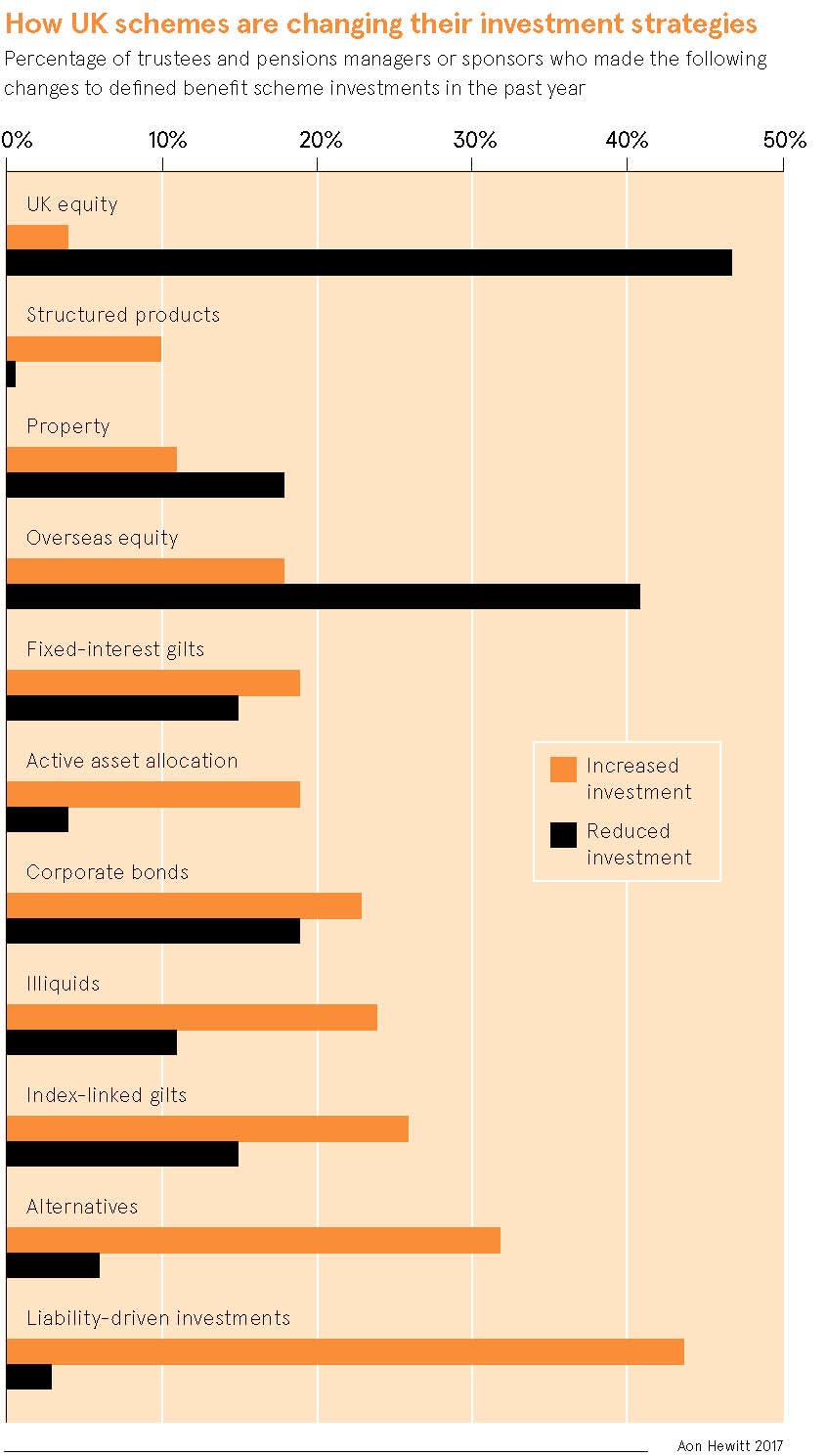

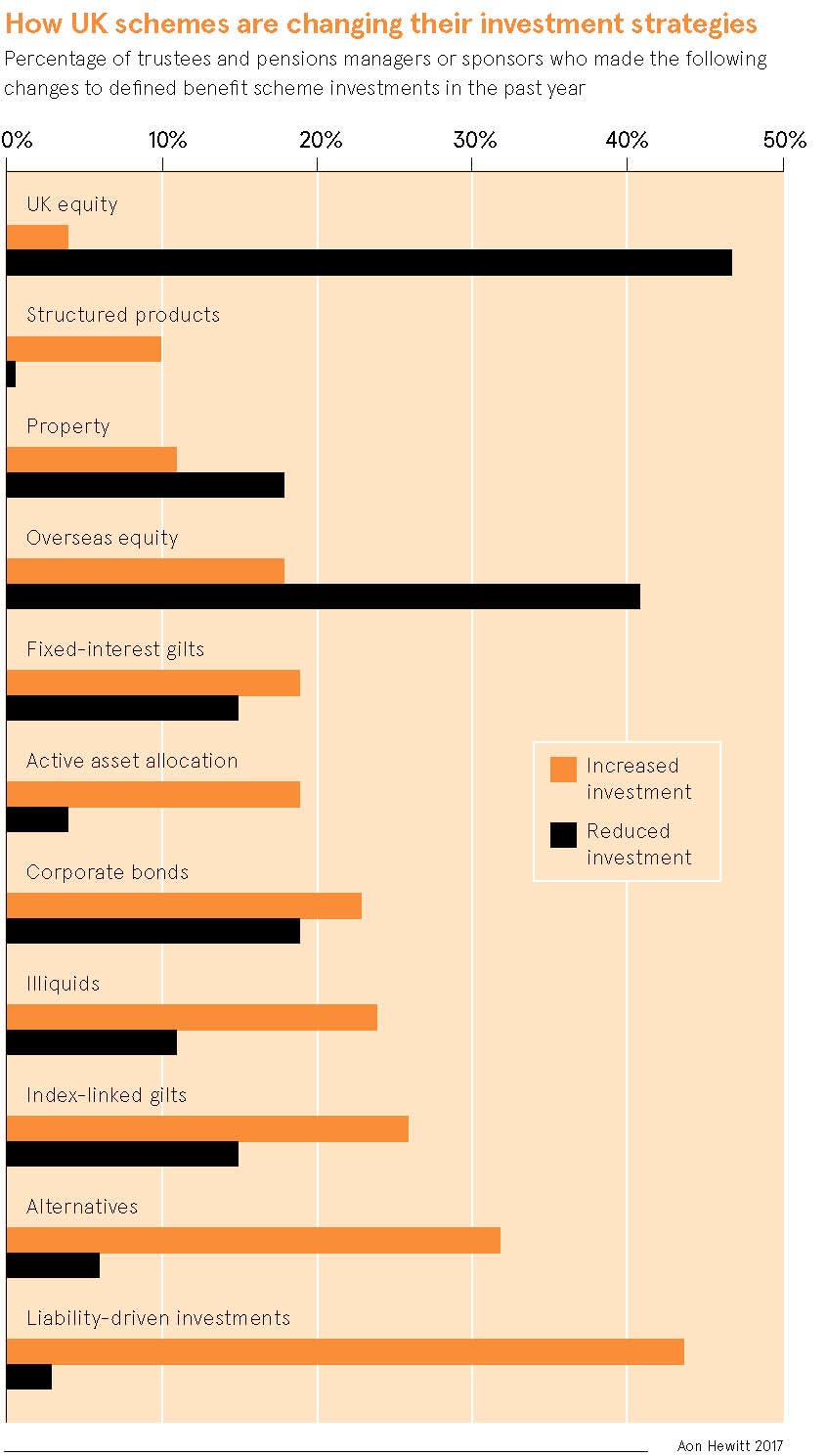

Schemes also do much to derisk themselves through, for example, careful matching of their investments to liabilities and adjusting benefit levels where possible. Doing this will also make them more attractive to an insurer should they choose to a buy-out later.

Schemes also do much to derisk themselves through, for example, careful matching of their investments to liabilities and adjusting benefit levels where possible. Doing this will also make them more attractive to an insurer should they choose to a buy-out later.

Buying is expensive, but can potentially save companies millions topping up funding levels in the long run. It usually also has advantages for scheme members. All deals come with the safeguards of the UK insurance sector regime, including the strong capital reserves required by regulators, and the back-up of the Financial Services Compensation Scheme if the insurer still fails. These typically compare favourably with the safeguards members get from staying in an employer scheme.

Insurance contracts will also typically include protections for members, for example, if the insurer is not able to pay the pensions on time or if unforeseen data issues arise. Some large deals also feature collateral structures to ensure schemes can recover their assets in the event of an insurer default.

Buy-ins are the biggest growth area as going straight to full buy-out is more expensive and beyond the means of most schemes

Charlie Finch, a partner at LCP, says buy-ins are the biggest growth area as going straight to full buy-out is more expensive and beyond the means of most schemes. “Also buying out in chunks can get you better pricing by targeting a set of liabilities,” he says. “For example, some insurers might prefer younger members, older members or those with larger pensions, so you could sell them to different insurers.”

Jeremy May, head of pensions at PwC, says more innovative buy-in solutions are also becoming popular, for example those that unbundle and customise the benefits without all the traditional costs.

“There is a whole suite of innovation,” he says. “You can mix some of the parts of a buy-in, such as longevity protection, inflation and interest rate protection, and specialist asset management, to suit your scheme’s needs. Also, there are cheaper buy-in solutions with more limited levels of cover and specialist firms that take over running the scheme to prepare it for buy-out.”

The biggest obstacle is cost, so schemes should beware any hard sell by insurers and advisers. They should also take care with any partial deals where the insurer gets the cheaper liabilities, such as pensioners with defined benefits, leaving the scheme with the more expensive ones such as deferred pensioners. The latter cost more to derisk because the benefits are less well known due to the timescales involved and unknown future variables.

Stephen Dicker, pensions strategy leader at PwC, says: “A partial buy-in or buy-out may still be the best option as a step towards full buy-out. But be sure that, if you are left with the more expensive liabilities, it won’t make a final buy-out deal look less attractive in future.

Stephen Dicker, pensions strategy leader at PwC, says: “A partial buy-in or buy-out may still be the best option as a step towards full buy-out. But be sure that, if you are left with the more expensive liabilities, it won’t make a final buy-out deal look less attractive in future.

“You might be better off retaining control of those assets and investing them to generate a slightly higher return. This could enable you to settle more of the liabilities with a buy-out sooner. The challenge is deciding where in that risk spectrum you want to be.”

Mr May adds: “Also a buy-in leaves more risk with the employer as the asset is still on its balance sheet. So it’s questionable whether the company’s investors will give you much credit for doing that.”

Most UK schemes are a long way from being able to make a full buy-out; the current £12 billion of insurance transactions a year is a tiny fraction of the £2 trillion of liabilities in defined benefit schemes. Most schemes need to get near to a state of full funding before they can afford a buy-out. But if they achieve this, they can invest in low-risk assets that match their liabilities and there is arguably then less need to insure. The cheaper option might be to keep the assets until the scheme is close to winding up, as administration gets proportionately more expensive at that point.

“Deals done earlier than that are often driven by additional factors, such as large corporate transactions where tidying the pension scheme makes sense,” says Mr May. “For example, Cable & Wireless derisked its pension scheme in 2008 prior to a demerger. ICI has done a series of derisking deals following takeover by Dutch firm Akzo Nobel. Also Philips completed a buy-out after splitting the business into two.”

Independent trustee George Taylor has worked at the coal face of derisking activities at several schemes. “In all cases, it started by moving steadily towards a lower-risk investment policy,” he says. “The downside of that is lower returns. But the regulator requires insurers to hold lower-risk assets, so you have to do that to make it insurable.”

Mr Taylor says two significant obstacles to a buy-out are often issues related to administration or data. “Pension schemes are complex and often have unresolved issues in their data,” he says. “The insurer won’t take them on with those issues because trustees can interpret them and exercise discretion, but insurers cannot. They have a more automated payment system. So it requires much work to tidy your data, administration and other issues, such as equality of benefits between members.”

The £3-billion Merchant Navy Officers Pension Fund (MNOPF) has been a derisking pioneer. The scheme has made several buy-ins since 2009, plus one buy-out and an innovative hedge of £1.5 billion of longevity risk in 2015.

Andy Waring, chief executive at MNOPF, says: “A significant improvement in funding enabled these moves, aided by the appointment of consultant Willis Towers Watson as delegated chief investment officer. This led to a plan to improve funding, which grew from 69 per cent in 2012 to 88 per cent in 2017 and is on target to achieve over 100 per cent by 2025.

“The success of this strategy, at a time when many other schemes’ funding levels deteriorated, enabled the fund to further secure its members’ benefits and saved over £300 million in deficit contributions for its employers.”