When chief executives make any major corporate decision they must consider a wide-ranging group of stakeholders. From employees and customers to shareholders and the local community, there are many interested parties that are vital to the long-term success and survival of a company. Concerns exist, however, that shareholder returns are increasingly being put above other business priorities.

Taekjin Shin, assistant professor at San Diego State University’s Fowler College of Business Administration, believes the balance of power between shareholders and executives has changed significantly over the past 30 years and, in the process, distorted how business leaders make decisions.

“Shareholders have become increasingly powerful and influential over the management. This made top managers more accountable to shareholders and generally contributed an increase in economic efficiencies, but it also prompted top managers to make decisions primarily based on the interest of shareholders rather than other stakeholders, such as employees, customers and communities,” he says.

CEOs who state shareholder value as a top priority in investor letters receive an average pay boost of $116,000 a year

One of the key reasons for the focus on shareholder returns by CEOs is the financial incentive on offer. Professor Shin published a study last year in the Journal of Management Studies showing that CEOs who state shareholder value as a top priority in investor letters receive an average pay boost of $116,000 a year.

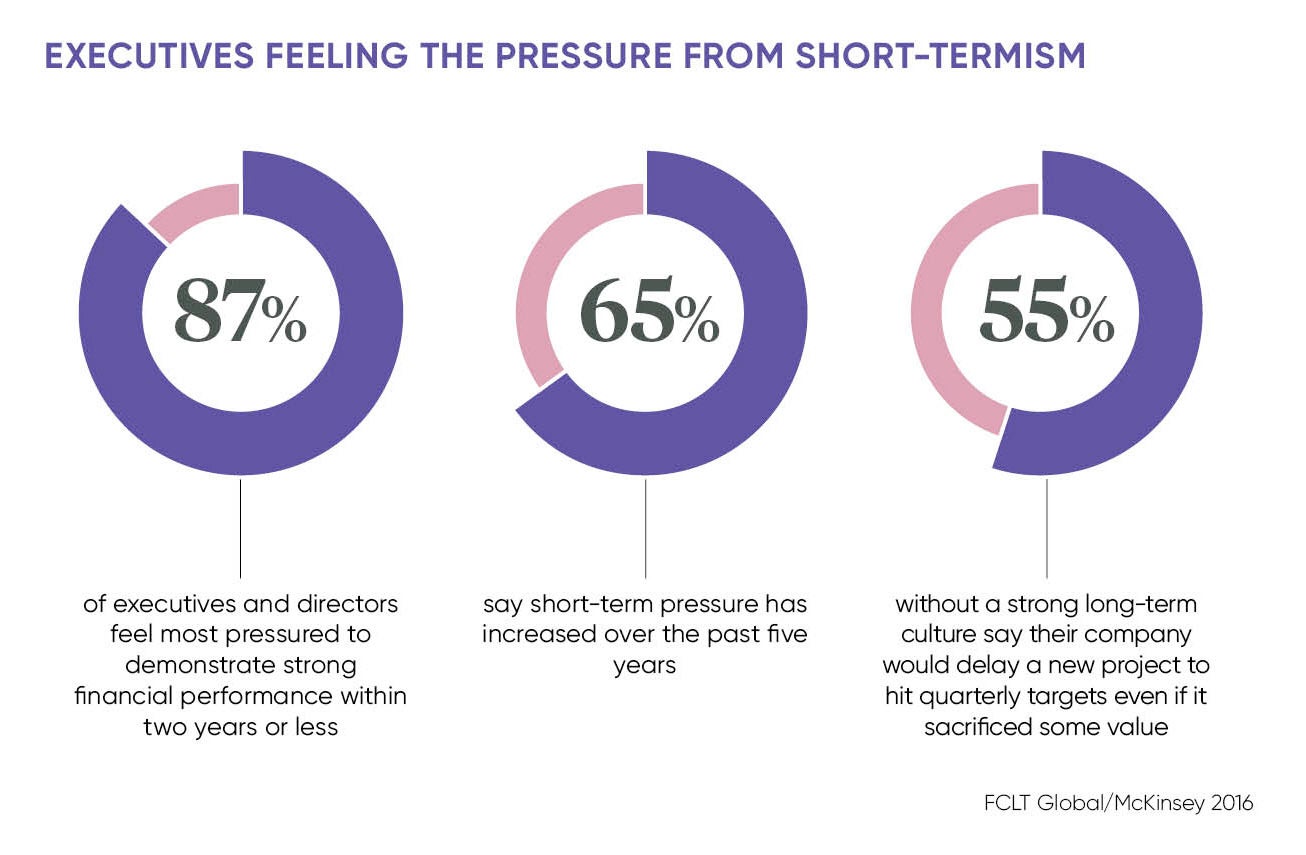

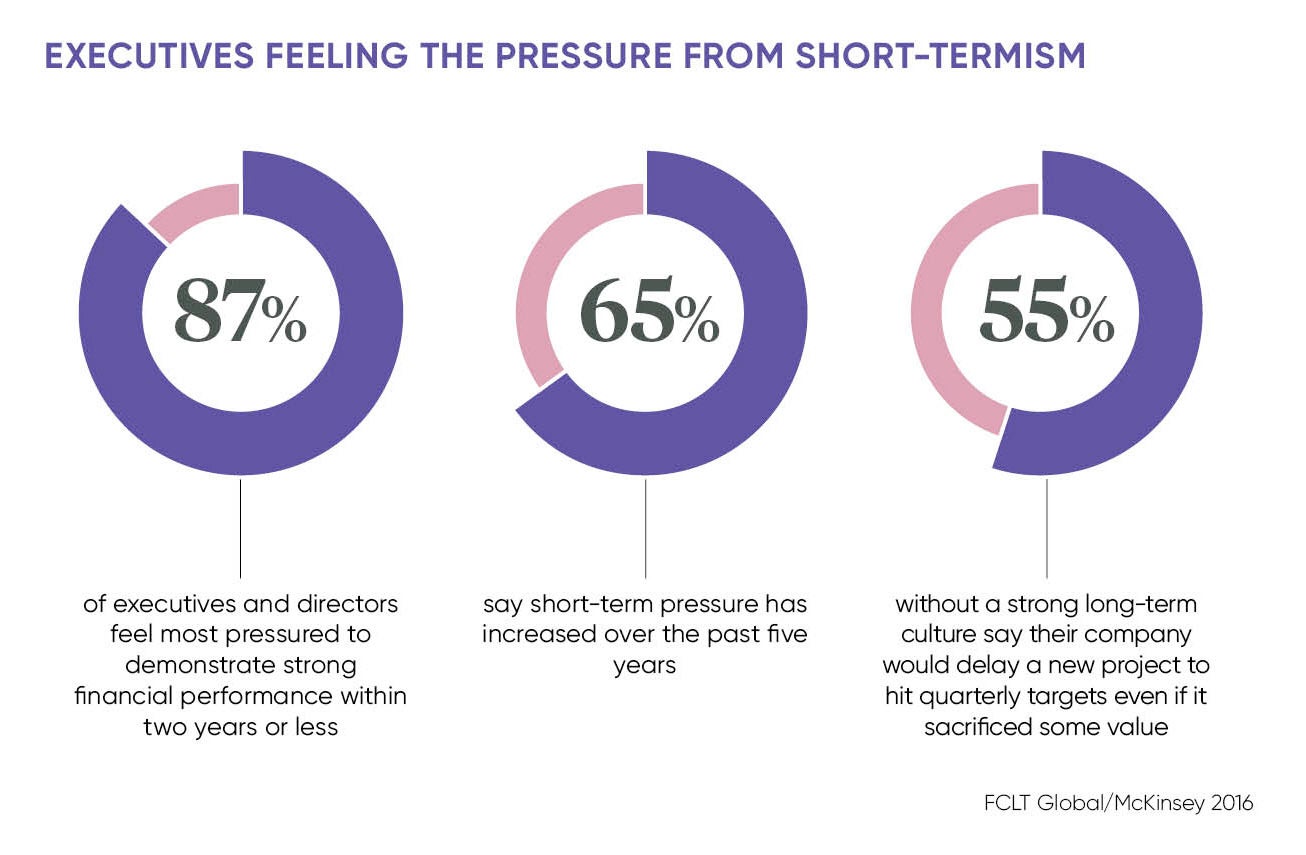

When the encouragement for CEOs to tout their commitment to maximising shareholder value is paired with lower shareholding periods, which have fallen from more than seven years in the 1960s to only seven months in 2007 in the FTSE, it’s not difficult to see why both leading executives and businesses are beholden to short-term pressures from shareholders.

Bank of England chief economist Andy Haldane argued in 2015 that strong shareholder power is not just causing slower growth in the wider economy, but also worsening corporate short-termism that focuses on current gains over longer-term success.

Allyson Stewart-Allen, who has advised multinationals including Grosvenor Estates, Coach and Burberry, and founded business consultancy International Marketing Partners, agrees that extreme shareholder centricity can have negative consequences.

“Only focusing on shareholders and not the wider world is not just short-term, but also leads to financial underperformance over time. Dr Peter Drucker, my MBA professor, is famous for saying ‘the purpose of a business is to create a customer’ – it isn’t to keep a shareholder,” says Ms Stewart-Allen.

There has been much debate around how damaging the search for immediate profits is for companies, with empirical evidence on this topic being scarce until very recently. Earlier this year, the McKinsey Global Institute released the Corporate Horizon Index, measuring the economic impact of short-termism, finding companies with a long-term view have significantly outperformed industry competitors that do not.

The index shows that publicly listed companies with a long-term mindset grew on average 47 per cent more than other firms, and spent close to 50 per cent more on research and development than their peers over the past 15 years. As the index demonstrates, overly powerful shareholders can hold back companies from being more agile and transformative.

“Shareholders in general do not necessarily prefer the companies that they invest in to become more agile or transformative; as investors, shareholders’ primary goal is to maximise returns to their investment,” says Professor Shin.

He explains that in the sectors where adaptability is valued, such as the high-tech and biotech industries, shareholders would be expected to reward firms that are more agile as this is needed for high performance. “In more traditional sectors, where stability and predictability are still important, shareholders would focus on the rate of returns, not necessarily on agility or flexibility,” he adds.

But as wildly successful startups such as Uber and Airbnb prove that practically any industry can be disrupted almost overnight, few companies will be able to thrive if they lack the ability to adjust quickly to markedly different market conditions. Of course, not all shareholders are transient, depending on their investment aims.

“Some institutional shareholders cannot easily shift investment portfolios, making it possible to adopt a more long-term prospect, while other shareholders focus on more short-term results. Depending on the actual composition of the shareholders, CEOs and businesses may have different time horizons,” says Professor Shin.

Ms Stewart-Allen concurs: “Increasingly, the pension funds that invest in plcs are asking for longer-term horizons to maximise their own returns.”

Shareholder-dominated firms may be the norm in the UK, but this is not the case in other European countries. German companies regularly include employees and other stakeholders in high-level business decisions and some French firms, such as media conglomerate Vivendi, offer long-term investors double voting rights, encouraging stakeholders to take a long view.

The shareholder-centric model many UK companies hold has been successful in the past, although there is an argument to be made that corporate governance laws have been slow to catch up to a new business environment, where close to £70 in every £100 of corporate profit is funnelled back to shareholders through dividends, compared with just £10 in every £100 in 1970.

This shareholder dependency is not expected to change any time soon, with the trading mentality of many shareholders causing concern. “Shareholders are generally not too concerned about the alignment of the business with its customers and it’s only with this alignment that the business will be viable,” concludes Ms Stewart-Allen.