In 2015, FTSE executives were paid 330 per cent more than in 1998. US CEO compensation rose 937 per cent between 1978 and 2016. American CEOs now earn 335 times more than the average worker; in the UK it’s 140 times more.

Anger at CEO remuneration in the belief it is a racket is now widely expressed among business figures as well as political campaigners. Former CEO Steve Clifford, author of The CEO Pay Machine: How It Trashes America And How To Stop It, says: “This system’s insane and it’s hurting a lot of people.”

There’s an absolute consensus now that executive pay is out of control

In the UK, David Pitt-Watson, a former CEO of Hermes Focus Asset Management, says: “There’s an absolute consensus now that executive pay is out of control.” He believes the UK’s “social contract” is at risk.

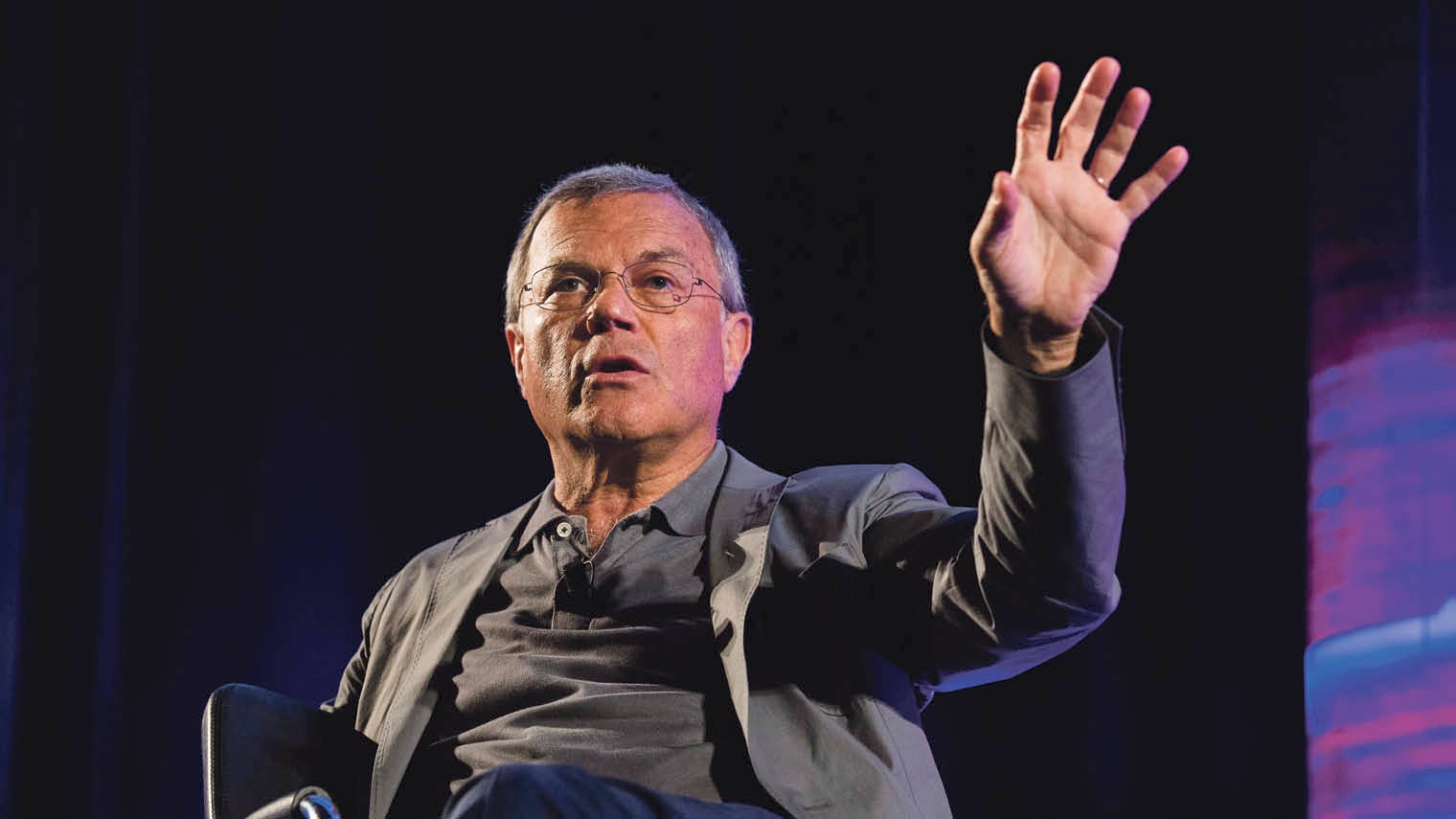

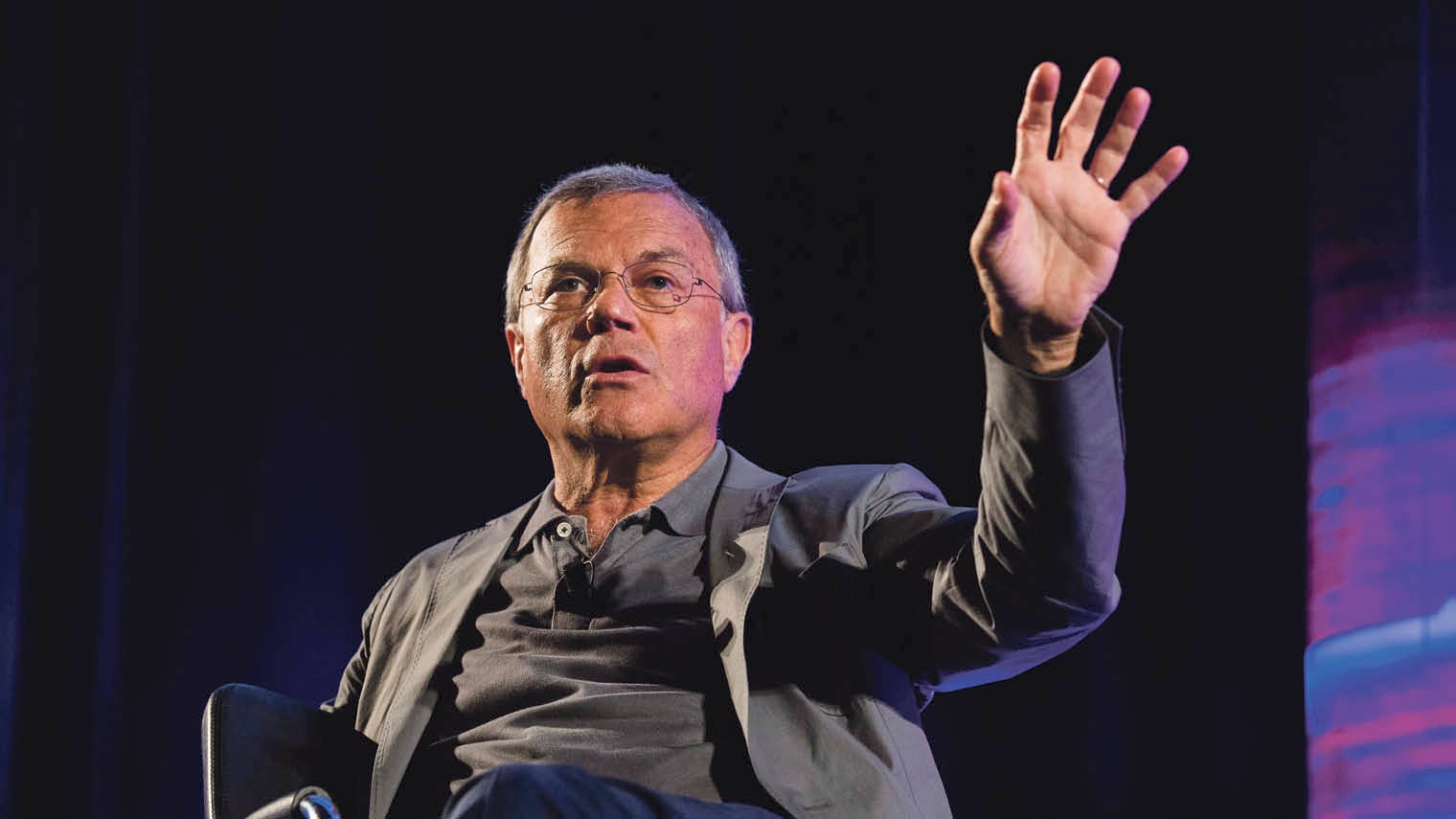

Sir Martin Sorrell, the FTSE’s highest paid boss at WPP, faces annual shareholder revolts. In particular, long-term incentive programmes, now the largest component of UK CEO pay, are slammed for encouraging short-term thinking.

Martin Sorrell, who received £48 million last year as CEO of WPP, regularly faces shareholder revolts over his pay

Academic studies suggest both competitive labour market conditions and “rent extraction” by CEOs contribute to rising CEO pay, but neither explain it fully. In a recent survey for the Harvard Business Review, 113 US non-executive directors strongly agreed CEOs have “specific skills extremely hard to replicate”. They thought fewer than four candidates were capable of doing the job of their own CEO and only six the job of a leading rival.

The authors suggest various implications, including an inefficient labour market, where executives face less pressure, and pay driven higher so boards don’t lose their top candidate. But they add directors must double-check their assumptions about talent scarcity.

A 2015 London School of Economics study of headhunters assessed there is luck “in being a candidate, in being chosen and in the choice turning out better than mediocre”.

Ashley Hamilton Claxton, head of corporate governance at Royal London, would like companies to conduct more imaginative searches and to develop internal talent, while acknowledging the pressure towards conservatism in high-stakes hires.

All this indicates the heat of the pay debate should go beyond fury at fat cats, to interrogating the market dynamics around remuneration.

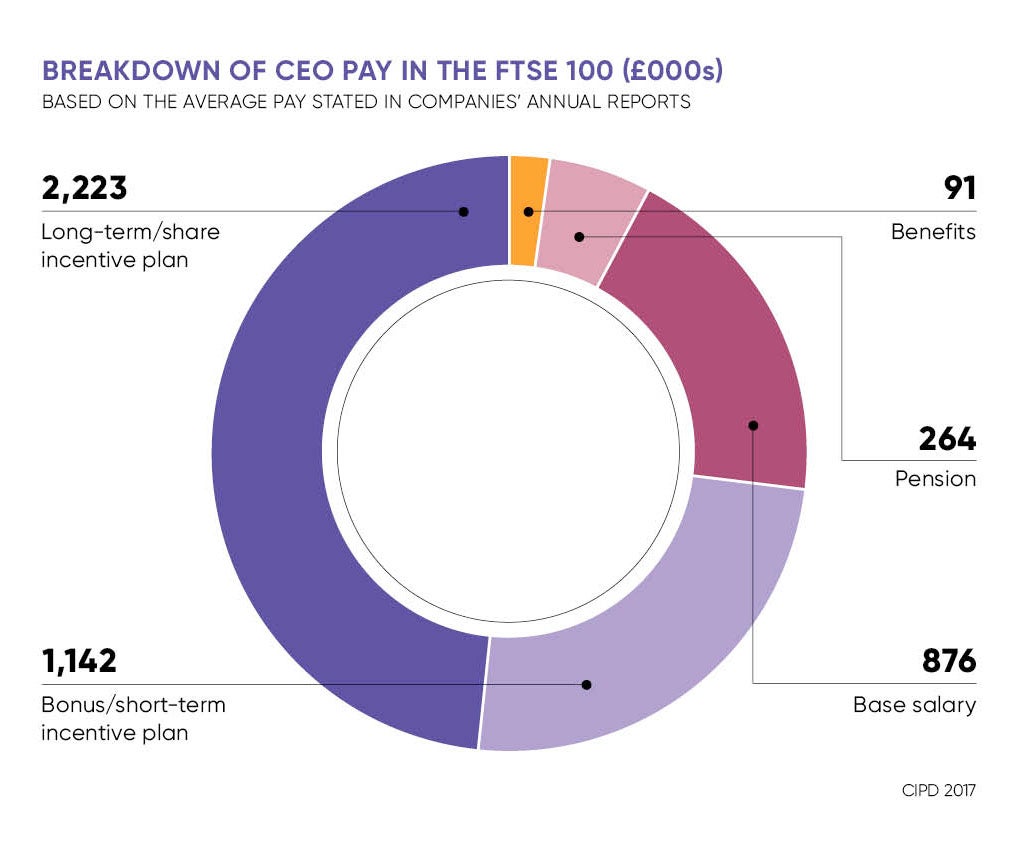

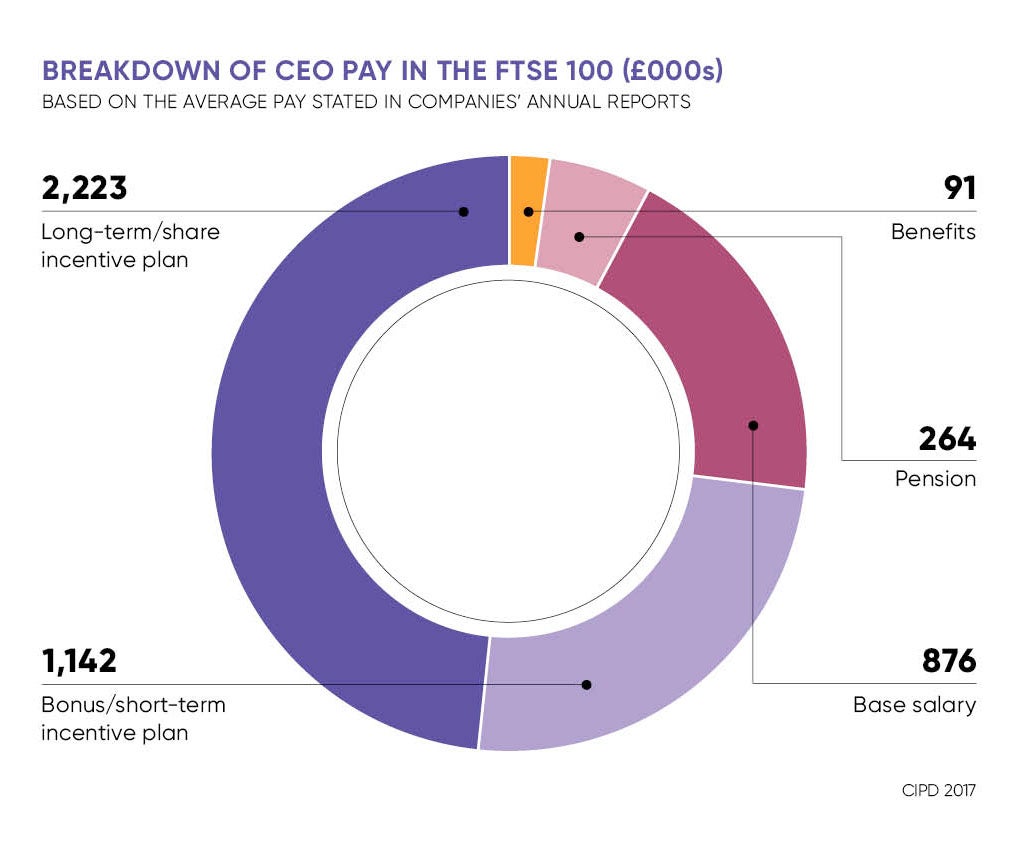

Looking at more tangible factors, rising CEO pay reflects larger company sizes. A recent PwC study found market capitalisation explains more than 60 per cent of FTSE pay opportunity variance. Another driver is internationalisation of the market for talent.

The “CEO effect” seems vividly demonstrated by the £1.3 billion (3 per cent) wiped off Prudential’s share price when Tidjane Thiam stepped down and the £2 billion (6.7 per cent) boost to his new employers, Credit Suisse.

Professor Alex Edmans of London Business School points to research showing the growing impact in recent times of a CEO’s death on company performance and that private equity companies in their drive for efficiency tend not to cut CEO pay.

Some commentators agree with the Harvard Business Review survey that there are very few suitable CEO candidates because of the experience needed and demands of the role, including responsibilities, media scrutiny and travel.

“What kind of personality types can do these things? You have to be almost a sociopath,” says Professor Len Shackleton of the University of Buckingham. Soaring pay is “inevitable in a world of imperfect information”, he says, likening corporates to football clubs seeking strikers.

Claudia Custodio of Imperial College London has identified a growing demand for CEOs with generalist skills to manage complex businesses in a fast-changing environment; this skillset commands a pay premium.

Any skill in scarce supply, which is scalable, will command a premium

In a globalised economy, any skill in scarce supply, which is scalable, will command a premium, argues Professor Edmans.

Then there is the political context. Attempts to make pay reflect solid performance trends rather than market movements have ended ramping up pay further.

Professor Kevin Murphy of the University of Southern California notes how since the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act came into force in 2010, CEO pay has continued to be attacked in the US media while shareholders overwhelmingly approve most packages. Get rid of all regulations and start from scratch to fix compensation, he says.

Professor Shackleton thinks the tax system, not intervention in business, is the right way to deliver greater income equality. Address poor growth in median workers’ pay rather than level CEOs down, argue the authors of this year’s PwC study.

Paying a CEO at least as generously as competitors and identifying them as closely as possible with the business has powerful effects, sending out a message of strength and injecting the company with ambition and purpose. Professor Edmans notes how CEOs with partner ownership outperform those with a lower amount of equity by 4 to 10 per cent.

Partner at PwC, Tom Gosling, says that in the UK “benchmarking” is now working the other way as companies retrench pay in response to rivals. Mr Gosling, who co-ordinates corporate governance consortium the Purposeful Company Taskforce, sees CEO pay as 80 to 90 per cent explicable, 10 to 15 per cent driven by “less than ideal” factors. “There is a healthy debate; in a couple of years we will be in a better place on this,” he says.

Certainly, the fascination with CEO pay, and the gulf between the corporate world and its critics, looks set to continue for a while longer.