The positioning of a CEO as a person of interest whose influence holds sway beyond the confines of their company, to shape industry and even society at large, is an important tool in brand-building.

For CEOs of the past, the art of influencing was a simpler endeavour, involving the privilege of giving keynote speeches at events, writing the occasional opinion piece, topped off with the publication of a ghost-written book revealing a personal business philosophy or illuminating life story, in the Horatio Alger tradition, much beloved in America.

Since around 2000, however, just as social media has reshaped social structures, it has reshaped the relationships between CEOs and their consumers, CEOs and their employees, and CEOs and their company’s brand.

“There is no such thing as a secret and you can no longer remain in the shadows,” says Leslie Gaines-Ross, chief reputation strategist at Weber Shandwick. “Customers and vendors can see leadership perfectly now and this has impacted leaders taking a greater role.”

Business, between 2000 and 2017, has been characterised by disruption. Companies everywhere learnt to take cues from Silicon Valley startups, to anticipate change and adapt. During this era of restless, impatient innovation, ideas gained a new currency. They were exhibited and traded through a global circuit of TED talks, tech conferences and festivals of ideas such as South by Southwest or SXSW.

Insight and thought leadership became a new commodity, and at the very heart of this climate of disruption was the notion of the “founder as prophet”. Indeed, some of the most noteworthy CEO-influencers of the last fifteen years – Jack Dorsey of Twitter, Biz Stone of Twitter and later Medium, Jeff Weiner of LinkedIn, Arianna Huffington of The Huffington Post, and Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook – in the United States created the very platforms that have been so instrumental in altering how businesses relate to consumers, and how CEOs present themselves to the world.

For the majority of Silicon Valley founders, continuity was anathema. Founder-CEOs amassed followers and customers through the strength of their ability to lead change, rather than be at its mercy. They became celebrities on that basis. Elemental to their appeal was the thrilling, powerful and unpredictable ability to disrupt, and with it to dictate, epitomised by the infamous Facebook motto, coined by a college-age Mark Zuckerberg: “Move fast and break things”.

We are now witnessing the beginning of the end of that mania for disinhibition and disruption. With the election of President Donald Trump, himself a former CEO and dubbed the “disrupter in chief” by the retired US army general David Petraeus, the public role of the CEO has undergone a short, fast maturation. Trump’s unpredictable character, whether deliberate or part of a scattergun strategy, and his tendency to personalise professional matters magnifies the febrile and uncertain state of economic, social and political affairs in America. As Republican lobbyist Bruce Mehlman says: “Disruption is hard… It usually leaves observers feeling exhausted, uncertain and ultimately either angry or exhilarated.”

Meanwhile in the corporate sector, a damaging deluge of sexual discrimination and labour actions in Silicon Valley have brought the responsibilities of companies to their employees, customers and society into sharp focus. For example, Uber, a company where several of these criticisms have converged, flouted convention and tested the reasonable limits of rule-breaking. Its founder and former CEO Travis Kalanick, was dismissed following a litany of leadership failures, which included allowing a “bro culture” to flourish, allegedly by his own example.

To succeed in the public game, CEOs first need to win the internal game, by removing internal barriers to growth, and providing the conditions for a productive and healthy corporate culture. Ms Gaines-Ross adds: “A more civilised CEO archetype is on the horizon and maybe that is in contrast to what we are seeing in some governments around the world which have turned pretty authoritarian.”

The appointment of Mr Kalanick’s replacement at Uber, Dara Khosrowshahi, is seen to typify a wider changing of the guard. Mr Khosrowshahi, Satya Nadella, CEO of Microsoft, and Sundar Pichai, CEO of Google, have much in common. Apart from being first-generation immigrants, they are all career managers, whose management styles are characterised by listening and being team players.

We are now seeing a backswing towards more professional and measured business leaders

Increasingly, CEOs are expected to fill the moral vacuum left by government. For many in the United States, government policies rolled out in 2017 have constituted an assault on the institutions and principles upon which the nation is founded. First there was the selective travel ban, then America’s withdrawal from the Paris accord on climate change, the axing of the Dreamers programme, which awarded citizenship to the children of illegal immigrants, and lastly President Trump’s equivocation on racial equality, demonstrated through his response to the Charlottesville protests.

“Government is increasingly looked upon as inefficient and unable to handle some of the bigger societal and environmental issues, and the public is looking to business to take on more of a leadership role and help solve some of the issues facing society,” says Ms Gaines-Ross.

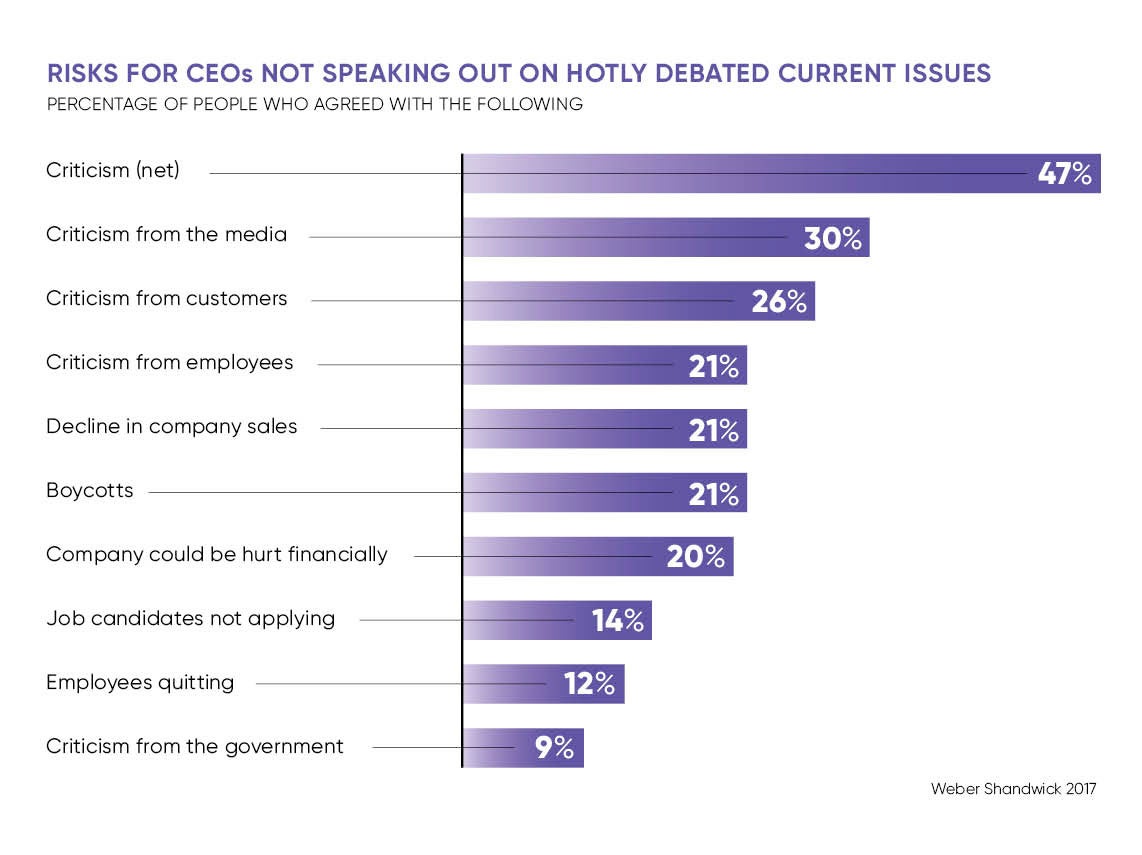

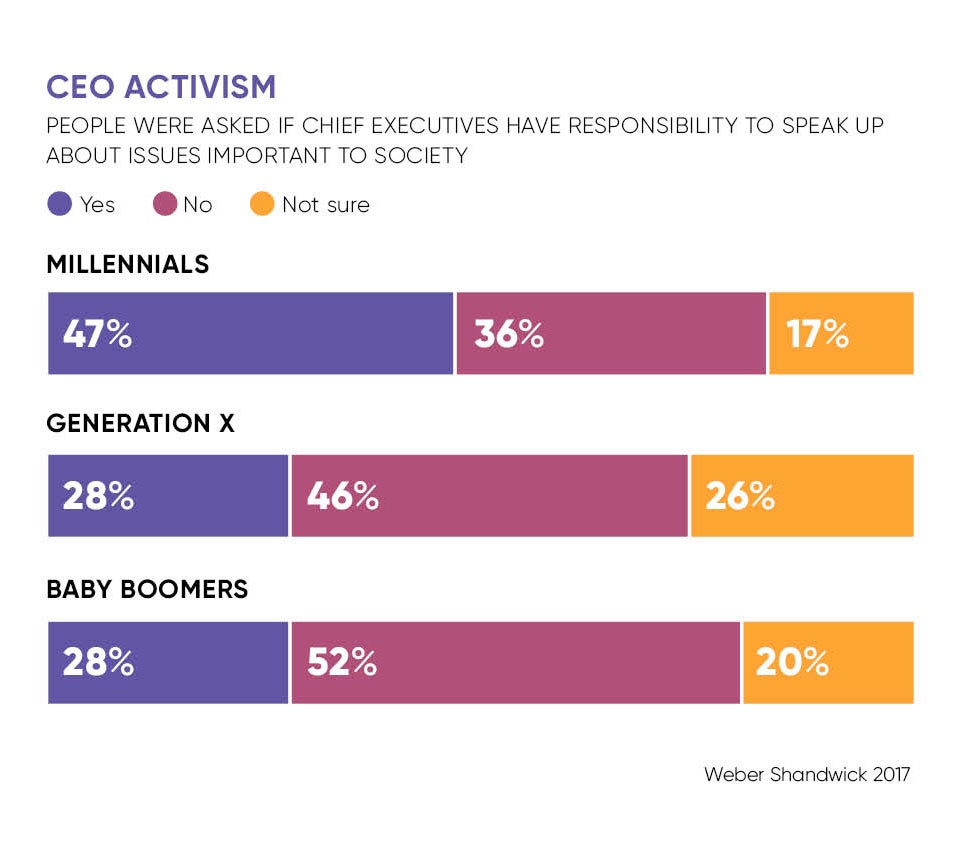

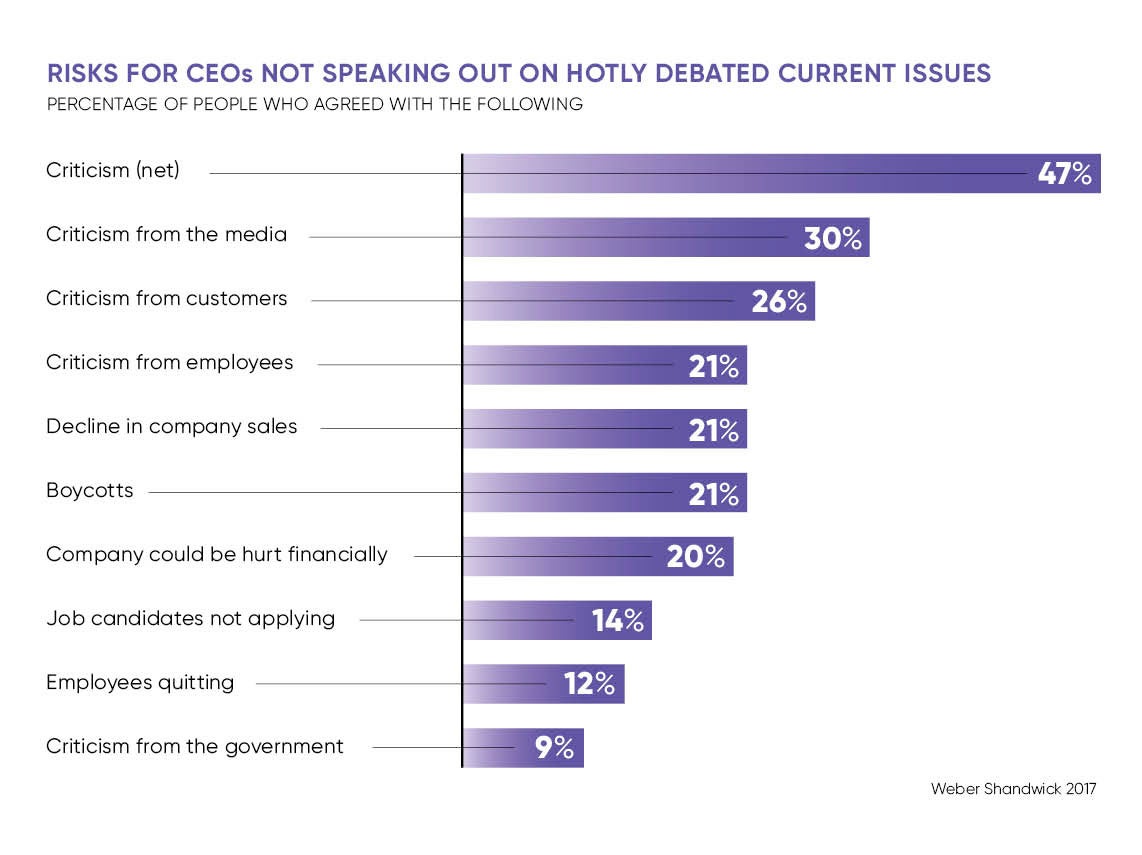

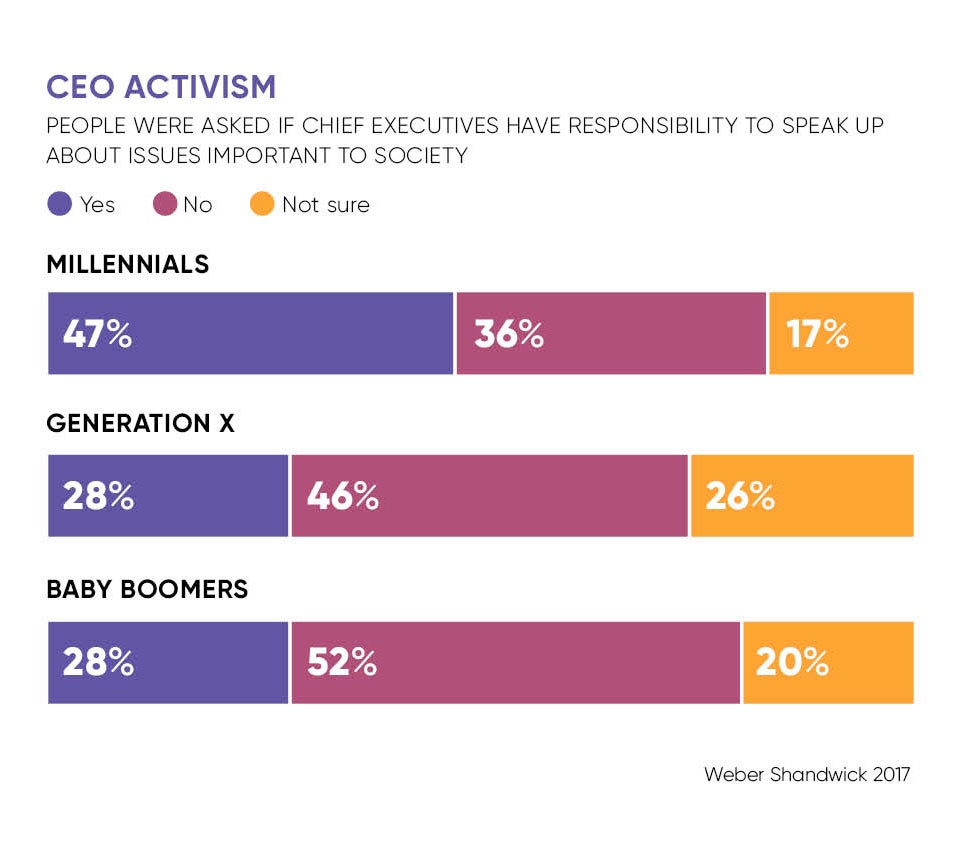

Many of these government policies had directly compromised companies’ values. Ms Gaines-Ross notes: “Many companies had invested significant time and money in establishing uncompromising core values such as diversity and inclusion.” Google, alone, had spent $265 million on diversity programmes between 2014 and 2016. Not only have CEOs been compelled to speak up, but remaining conspicuously quiet can adversely affect an organisation’s ability to hire, especially among younger recruits. According to Weber Shandwick, twice as many young adults would feel more (as opposed to less) loyalty towards their CEO if he or she took a stand on a contentious public issue (44 per cent compared with 19 per cent respectively).

The CEO role is a tricky one to fill. From 2000 to 2013, approximately a quarter of the CEO departures in Fortune 500 companies were involuntary, according to the business membership group Conference Board. While entrepreneurial energy can provide a catalyst for growth, untempered it can also lead to arrogance. Too often, inexperienced founders have been heedless of the broader social, political, legal and economic contexts in which their companies operate.

Perhaps we are now seeing a backswing towards more professional and measured business leaders. Whatever a CEO’s background, to be an asset to their company rather than a liability, the simplest maxim still holds true: “Work hard and be nice”.