Top banker António Horta-Osório was headhunted by Lloyds Banking Group to lead the organisation’s turnaround after the financial crisis that brought it to its knees. But within a few months of taking up his appointment, Mr Horta-Osório was standing before his chairman announcing that he was taking time off, with immediate effect.

The job of turning around the bank’s fortunes was barely started, yet the chief executive was about to take a leave of absence and nobody could say when, or even if, he might return.

António HortaOsório, CEO of Lloyds Banking Group

By his own admission, the pressure of taking responsibility for a banking colossus, with billions of pounds and thousands of jobs at stake, had shattered his mental health. Mr Horta-Osório spent nine days at a Priory clinic, receiving treatment for insomnia.

Supported by his family and by his employers, he was able to make a full recovery. Not only did he return to work, but he led Lloyds to become the first, and so far only, bank rescued by the government fully to repay taxpayers’ money.

At this point it must be stressed that it is not unusual for people to make a full recovery from a mental health problem. Nor is it unusual for people with a mental health issue to be successful. What sets Mr Horta-Osório apart as CEO is that he took the unusual step of going public about his illness and, more importantly, his recovery.

Although great progress has been made in confronting the stigma of mental health in the workplace, it is still extremely rare for a senior business executive to step forward and admit such vulnerability.

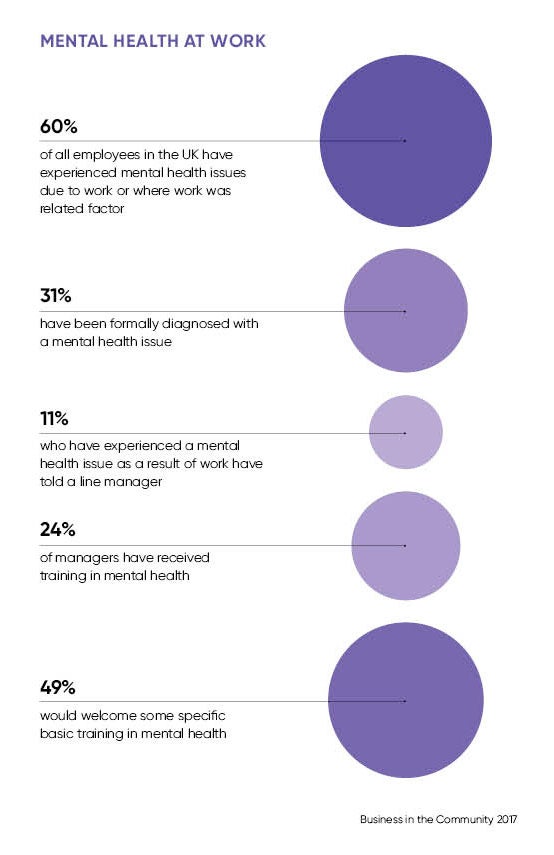

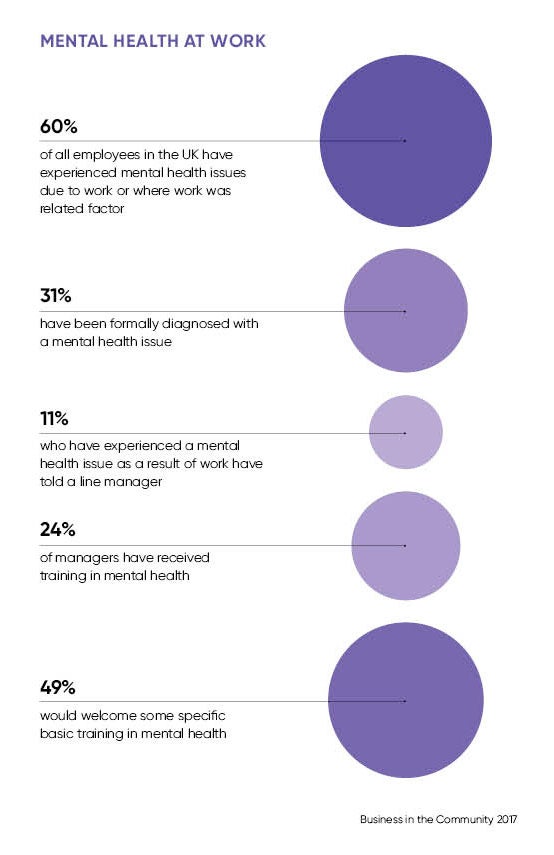

This cannot be because they are less prone to mental illness. Studies show that mental health problems across the population affect one in four , while Business in the Community’s Mental Health at Work report gives valuable insight into the prevalence of mental health problems in the workplace.

Research suggests that authority may be linked with depression and that CEOs may be at twice the risk of the general public

If anything, many of the tendencies that propel business leaders to the top – determination, commitment, working under extreme pressure – appear to increase the risk of mental health problems. Research suggests that authority may be linked with depression and that CEOs may be at twice the risk of the general public. Also, reaching the top can disconnect you from the people you trusted in the early days, creating a sense of loneliness and alienation.

It seems that while business leaders are doing what they can to create open and inclusive cultures in the workplace to encourage employees to seek help for mental health problems, many CEOs are still unable to speak openly about their own vulnerabilities. That is why business analysts believe that the next big hurdle for mental health is in the C-suite, with more people in leadership positions acknowledging and addressing the need for open acceptance and discussion of their mental health.

Lord Stevenson of Coddenham is a leading campaigner of mental health. A former chairman of HBOS, another bank stricken by the financial crisis, and of Pearson, he has spoken publicly about living with depression while at the top of his career. It was not easy managing his illness in an environment where the chairman and chief executive are expected to exude confidence and poise, and to epitomise success.

He estimates that in the top hundred companies a quarter of those running them have, or have had, mental illnesses, but few have openly acknowledged it.

One CEO who has spoken about living with depression is Virgin Money’s Jayne-Anne Gadhia. Her illness became particularly acute after the birth of her daughter Amy in 2002 and again three years ago when she had to suppress suicidal thoughts at the same time as Virgin Money was preparing for a stock market flotation. Ms Gadhia writes about her depression in her autobiography, The Virgin Banker, which was published earlier this year with proceeds going to the mental health charity Heads Together.

Jayne Anne Gadhia, CEO of Virgin Money

After many months of suffering, she eventually went to the doctor and clinical tests showed she was suffering with depression. As part of her care she started working shorter hours, took exercise and put her life back into balance. She says a healthier work-life balance wasn’t just good for her and her family, it was also good for work. The first year she changed the way she worked, Ms Gadhia received the highest bonus of her career.

At Lloyds, steps have been taken to support senior executives and to reduce the risk of others suffering as Mr Horta-Osório did. The bank has introduced a 12-month leadership resilience programme. Undertaken by 200 top executives, it is designed to raise the performance of individuals, while reducing the risks associated with increased demands and workloads. It includes nutrition analysis, methods of cognitive behavioural therapy, mindfulness, and psychological and physiological testing. The hope is this programme will reinforce an organisation-wide culture of wellbeing that will benefit all employees.

Seeking to harness Lord Stevenson’s experience and knowledge, prime minister Theresa May asked him to lead an inquiry into the state of workplace mental health. His report, Thriving at Work, co-written with Mind CEO Paul Farmer, was published earlier this month in November. It found that poor mental health at work is costing employers up to £42 billion a year in lost productivity, staff absences and presenteeism. It made a series of recommendations aimed at improving workplace mental health and wellbeing.

A clear message was the need for senior management to lead by example, and that sometimes can mean standing before colleagues and admitting physical or mental vulnerability.

One of the biggest challenges for CEOs is to accept the advice that is now being shared with employees as part of corporate wellbeing strategies – don’t suffer alone, learn to manage your stress, understand that depression is common and treatable, maintain a balanced life. For good C-suite mental health, the time has come for CEOs to walk the talk.