In his high-profile November lecture in memory of the distinguished economist G.L.S. Shackle, the Bank of England’s Andy Haldane lamented the fact that economics in general and finance in particular had been particularly slow to learn from other disciplines. It was, he said, the worse for it. Other sciences had gained great insights by applying thinking developed in other fields; finance was only now coming to recognise that psychology and other human behavioural issues often played a huge part in successful business outcomes.

Interestingly another economist Andrew Smithers made a similar point in his 2013 book The Road to Recovery in which he lamented the decline in the levels of business investment in the UK and United States not just since the financial crisis but for ten or more years before that.

Smithers’ thesis was that a major structural problem was lurking unseen. He argued that changes in the way executives were paid had made them excessively risk averse. It was now commonplace for them to collect big pay bonuses if they hit certain short-term financial targets. Accordingly they would not take the routine risks associated with investment for the longer term if they thought the costs might mean they fall short of their short-term goals. And the doubly interesting thing is they might not even be aware they were influenced in this way, and might not even have calculated those investment risks correctly.

These words should strike a chord with finance directors as they struggle to shake off their “scorers” label – that they should confine themselves to the numbers and nothing else. Modern technology has taken much of the drudge out of their traditional role because it is now possible to get fast and accurate information rapidly from even the most far-flung and complex operation. This frees them up to apply their financial awareness and facility with numbers over a wider canvas.

Business integration

It is time for those who have not already done so to raise their sights to become an integral part of the team alongside the chief executive. They need to be in there helping to implement business strategy, not simply measuring and monitoring their outcomes.

American author Daniel Kahneman, surely the only winner of the Nobel Prize for Economics to describe himself as a psychologist, has shown one way this might work. He has written that if investment risks are assessed individually, the outcome is different from what you get if they are assessed collectively. It is summed up in the phrase “you win some and you lose some” and Kahneman’s view is that this is the approach companies, and indeed private investors, should take because the future is inherently uncertain and no one can ever be sure how an investment will work out, however much homework they do beforehand. The way to cope with this is to accept some will fail, but they won’t all fail and to design strategies accordingly.

That means in effect the business will be advanced if it puts in place a portfolio of investments on the understanding they will not all pay off. This is where the chief financial officer is important. If the finance department continues to insist that each of these investments is assessed individually on its own merits, the odds will be tilted against each in turn because of the executive’s psychological fear that this will be one which turns out to be the loser. The result overall will be the business will not invest as much as it could or it should.

A warning

Alternatively if the chief financial officer insists on a portfolio approach to risk assessment, the result will be different.

However, it does mean the finance chief has to raise his or her game. It goes against the grain for them to say “too much detail”. It takes them out of their comfort zone to say “ignore the individual losers because it is the average performance which matters”. But if they cannot do this the business will be more risk averse than it should be and performance will suffer.

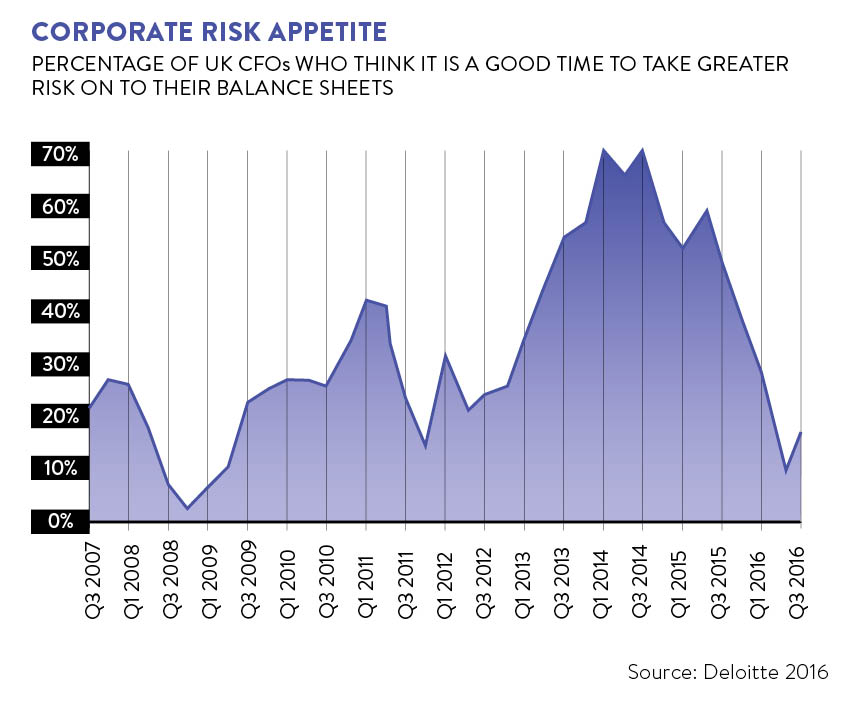

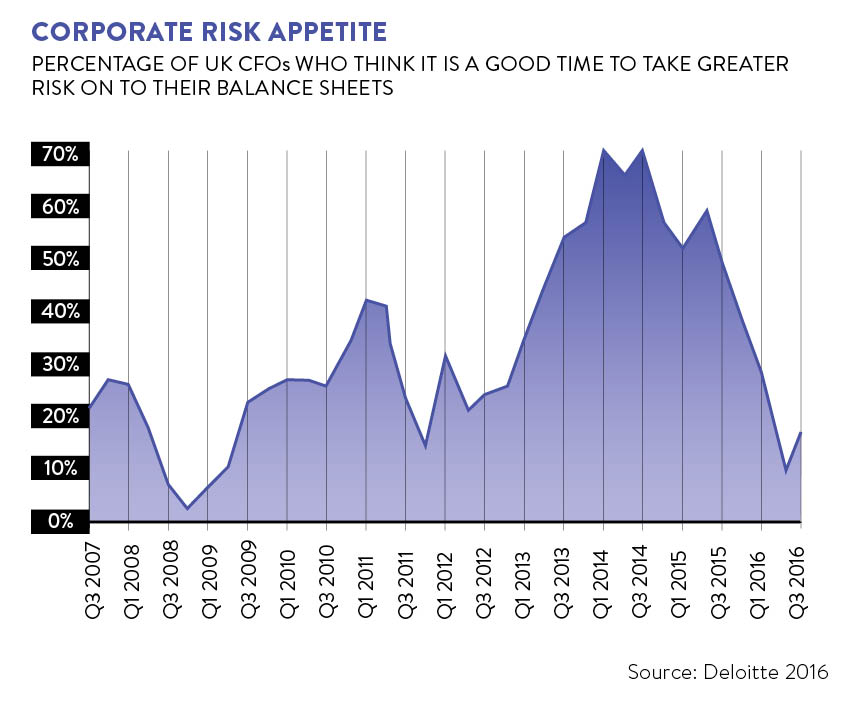

This thinking has implications for the whole economy, not just individual companies. It is interesting to look at what it is that has driven profits growth in recent years in UK companies to compare this with the drivers in other countries. Anecdotally, what you do find is that the recurring source of margin improvement in the UK has been from cost-cutting, plant closures, streamlining and rationalisation, so there are finite limits in what can be achieved. By contrast in Germany growth has come from investment, raised productivity and expansion, so theoretically the sky is the limit.

Business in the UK is dominated by finance, while in Germany it is dominated by engineers – and it shows. For UK business to optimise its future, finance needs to rethink its attitude to risk.

Business integration