When giant companies with devilishly complex tax arrangements are accused of unethical behaviour, the stock response is “we act within the rules”. If the public and politicians don’t like it, the argument runs, they should change those rules.

Presented with the apparent contradiction between a gargantuan turnover and the skinny profits that can result in a trifling tax bill, defenders of multinational businesses will often explain that it’s their job to improve financial efficiency in any way that’s legal, not to set tax law.

Does that hold true? Is it really the chief financial officer’s job to reduce the tax bill at all costs? It’s not quite so simple, says Matthew Rowbotham, partner and head of tax at law firm Lewis Silkin. There is, of course, no obligation for English companies to minimise taxes. They are, however, obliged by law to promote the success of the business.

“That specifically requires a balanced approach to a range of factors, not a narrow focus on net profit maximisation,” says Mr Rowbotham. Listed companies also have additional considerations under the corporate governance code that promote “transparency, risk management and accountability in corporate decision-making”, he notes.

Dodging tax

That sounds like a description of exactly what some believe is lacking when big businesses establish elaborate structures to take advantage of the gaps in international tax rules.

However, following a series of tax scandals, including this year’s ruling from the European Commission that Apple must pay back the Irish state up to €13 billion in taxes after it was found to have been given an anti-competitive “sweetheart deal”, the mood appears to be changing.

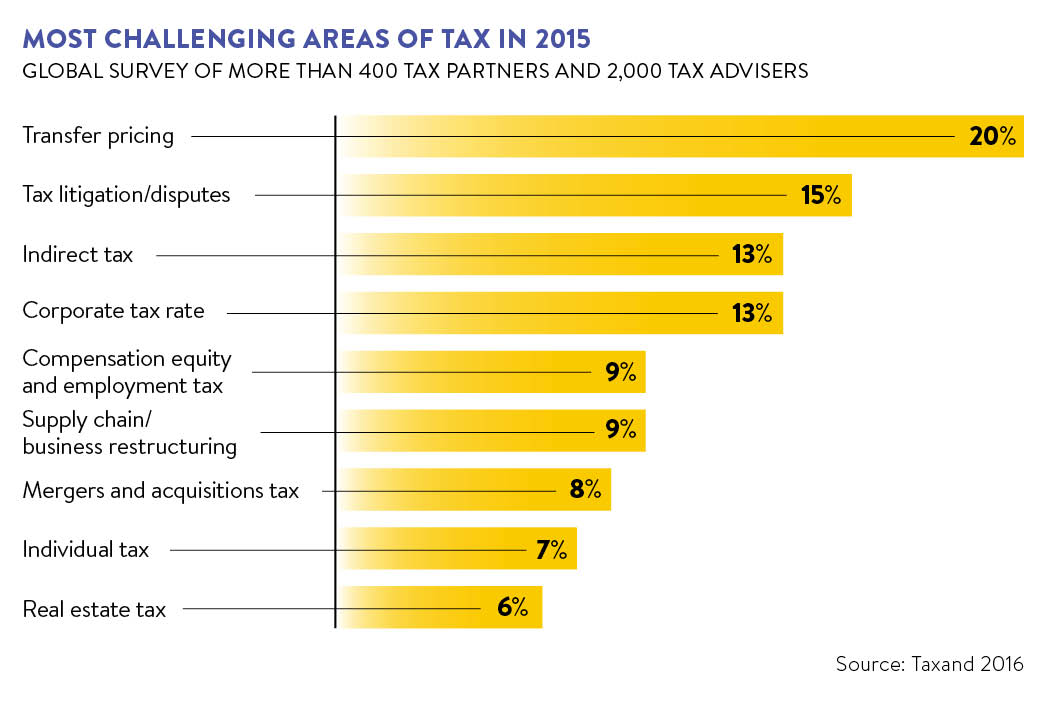

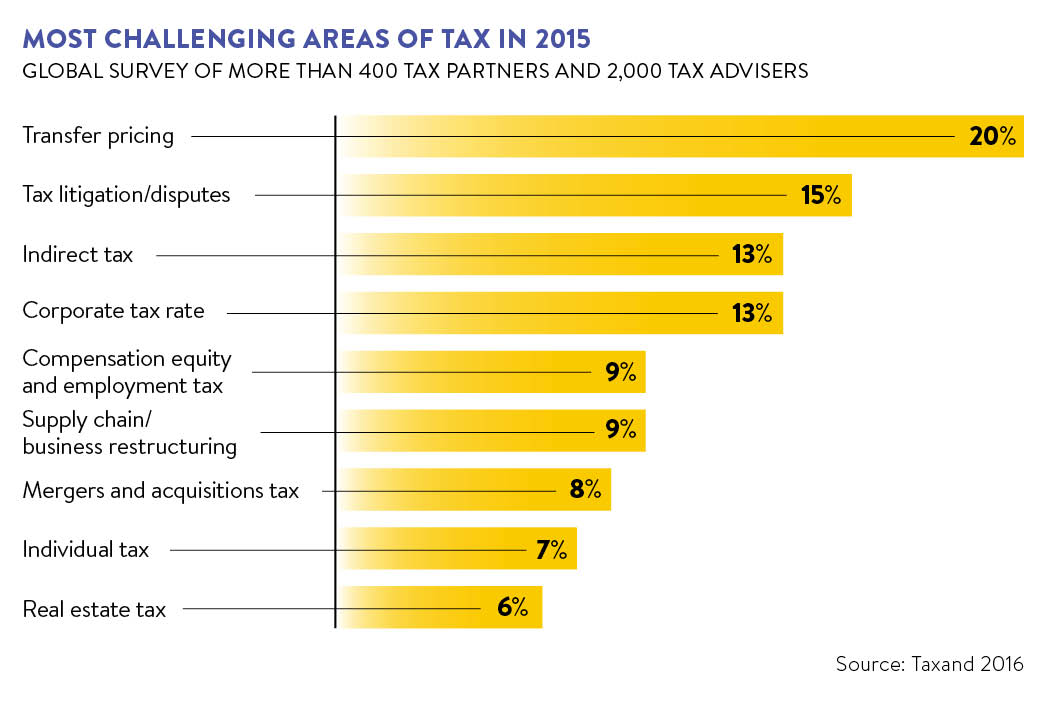

Tim Wach, managing director at Taxand, the global tax adviser, says: “The last decade has seen political and public perception of [tax] planning change dramatically, with people seeing any form of planning as damaging to reputation and a corresponding increase in tax audits by authorities globally.

“Our recent survey found that 77 per cent of CFOs and tax directors said they have seen an increase in the number of audits undertaken by tax authorities in the past year – up from 60 per cent who said this in 2015.”

While the pressure for chief financial officers to reduce taxes can be intense, he notes that companies are becoming increasingly aware of a “negative view of tax avoidance”.

Taxand’s survey found that 91 per cent of chief financial officers and tax directors believe that exposure of a company’s tax policy has a detrimental impact on a company’s reputation, up from and 51 per cent in 2011.

The moral dimension in tax is now important to high-profile businesses

Laurence Field, head of tax at accountants Crowe Clark Whitehill, says: “Your job is to maximise profits, shareholders tell management. In the past this has been used as an excuse to maximise returns through aggressive, but not illegal, tax planning schemes.

“These days the position is more subtle; your job is to maximise profits at a sustainable level, say shareholders. With greater focus on the moral and ethical issues surrounding tax avoidance, companies don’t want their businesses disrupted through [a taxman] investigation or adverse publicity.”

The result?

Chief financial officers have stopped asking whether a tax structure simply works and are now focused on thinking about what it could look like, regardless of whether the law allows it, Mr Field argues. That can result in a confusing position for the finance chief.

“The moral dimension in tax is now important to high-profile businesses. Campaigners, the press and tax authorities have… [discouraged] businesses from simply following the law. They want business to follow the law as they would like it to have been written, rather than how it is written,” he adds.

With the risk of falling foul of regulators as well as public opinion, understanding and warning management of the potential downsides to aggressive tax planning has become as much a part of the chief financial officer’s role as considering potential tax savings, Mr Rowbotham notes.

“A director might be in breach of company law if they mismanage a company’s tax affairs, but they are unlikely to be criticised simply because they considered, and rejected, a planning opportunity which in their view presented a business risk,” he says.

“The concern might be about the risk of an HM Revenue & Customs challenge or the damage to brand caused by media coverage. There’s no point shooting for a lower tax rate if it causes your profits to plummet when you’re criticised in the press.”

Legislation introduced in the 2016 Finance Act now requires big business to publish their tax strategy. “Affected companies will need to decide where their own risk- reward boundaries lie,” says Mr Rowbotham. “Of course, the government is hoping that the very act of formulating and publishing a tax strategy will make businesses think twice before pursuing any kind of tax avoidance.”

While complexity has allowed some companies to minimise their tax bills, most chief financial officers crave clarity, says Taxand’s Mr Wach. “There aren’t any easy answers. What is certain is that CFOs and tax directors want consistent and clear guidance as to what is acceptable and what is not,” he concludes.

Dodging tax