The relationship between sales and marketing has often been fraught. Marketing people feel they do most of the work, then sales closes the deal and walks away with all the kudos – and quite often a bonus payment, too. Sales, meanwhile, think marketing never actually meet a real customer and all leave the office at 5.30 when the salesperson is still a two-hour drive from home.

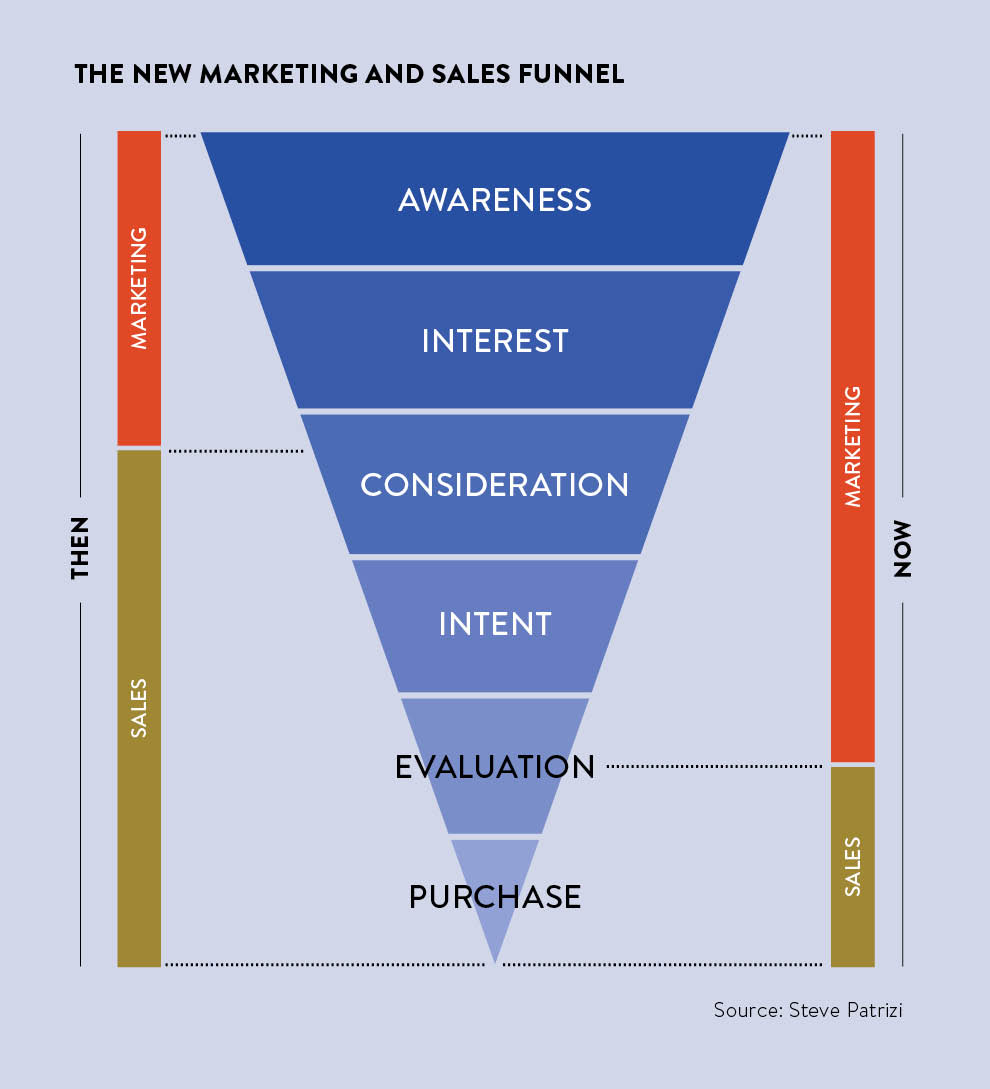

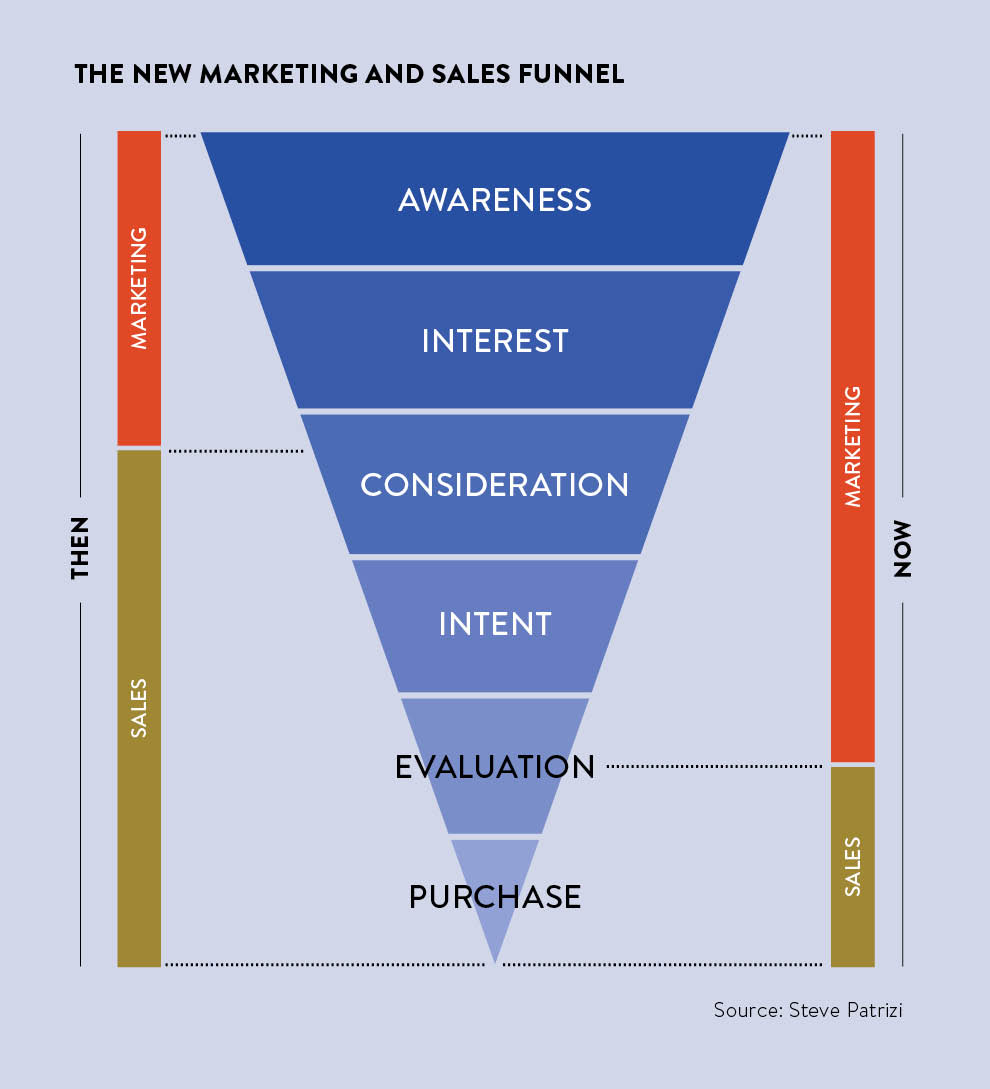

So, how is digital technology impacting on this tricky relationship? Traditionally, the marketing funnel positioned marketing as the upstream activity: identifying segments through market research, developing brands and appropriate value propositions, pulling together appealing marketing materials, and even setting up appointments for sales teams to attend. At this point, “ownership” of the customer relationship would be passed over to sales to complete the transaction.

Customer retention

Then, suddenly, companies woke up to how costly this process was. In his 1996 book The Loyalty Effect, Frederick Reichheld pointed out that it might take years for a new customer to become profitable. He also showed that a 5 per cent increase in customer retention led to a whopping 35 to 95 per cent increase in their lifetime value.

Not surprisingly, in response, focus shifted to customer retention. At this point, there was something of a divergence between business to business (B2B) and business to consumer (B2C). In B2B, salespeople claimed ownership of the customer relationship and turned themselves into account managers with matching salary and status enhancement. In B2C, personal selling was increasingly viewed as uneconomic and salespeople were replaced by digital marketing supported by customer relationship management (CRM) systems.

Since then, rapid developments in digital technology have revolutionised customer information-seeking behaviour as well as the act of purchasing. By 2014 Adweek was reporting that 81 per cent of B2C customers carried out research online before going into a store. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) found that three quarters of UK consumers now shop online. Many – 48 per cent of men and 37 per cent of women – prefer it, according to the ONS this June.

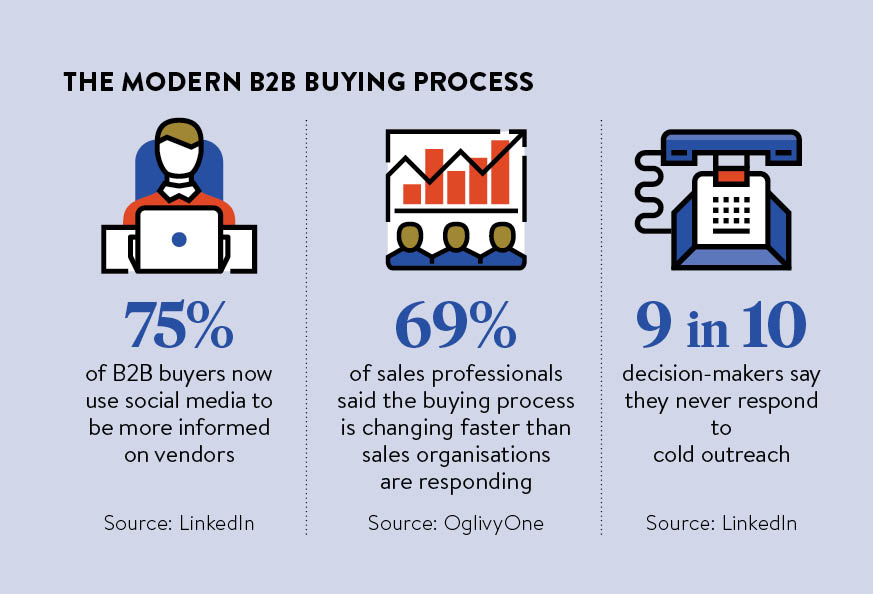

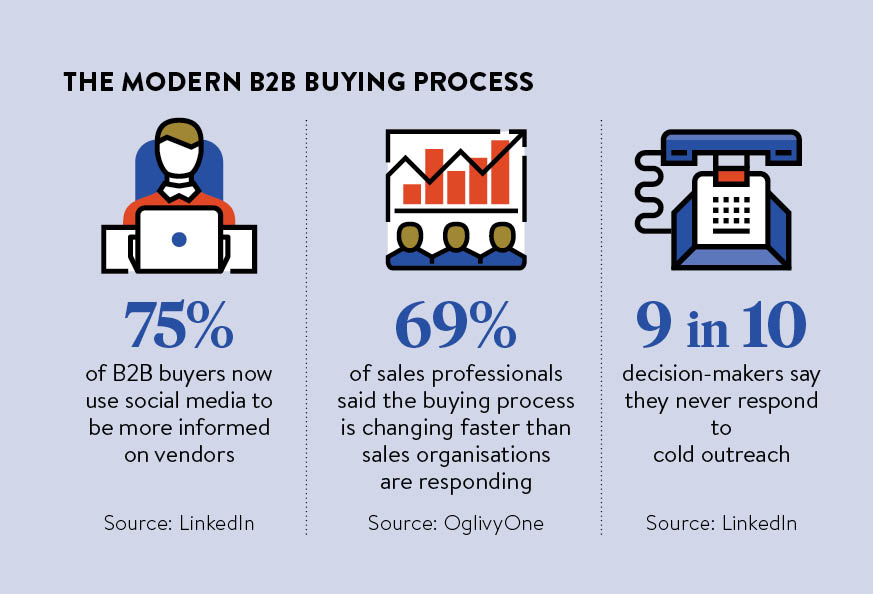

Digital marketing is increasingly making its presence felt in B2B. The role of the salesperson is no longer to describe a company’s products and what they can do, or to take orders, as the customer can now do that far more effectively online. Not only can consumers research products and often sample them online, they can order, pay and trace their delivery. Given the CRM systems that manage all of this are commonly the responsibility of marketing, it looks as though marketing is the new sales.

“Decision stickiness”

But is it too soon to call the death of the sales function? There still seem to be a surprisingly large number of sales roles; sales is frequently represented at board level and sales salaries seem to be comparable or higher than their marketing equivalents. Why might this be?

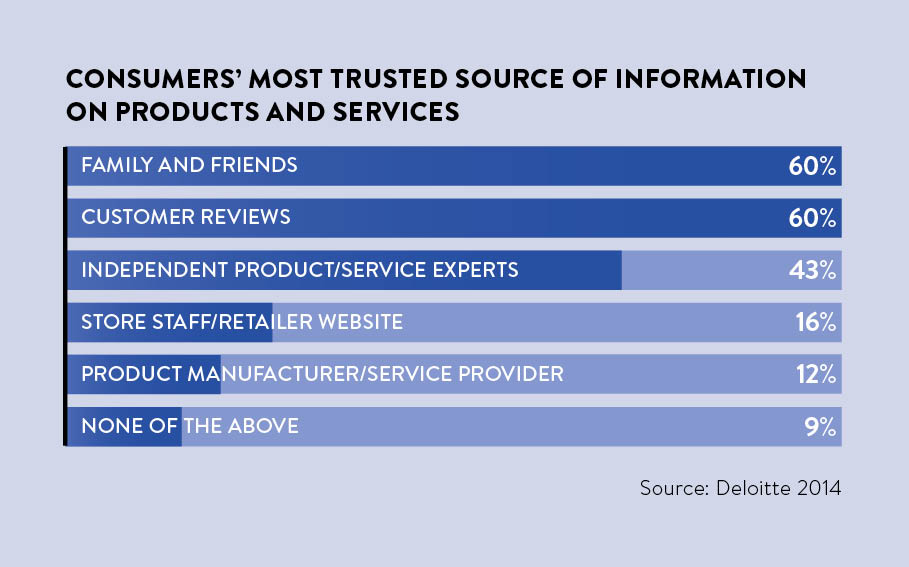

Perhaps an answer lies in research by Spenner and Freeman reported in the Harvard Business Review in May 2012. They found that by far the strongest driver of purchasing is “decision stickiness” which has three components: ease of gathering and understanding marketing information; trust in the brand; and ability to weigh their options. Scoring well on all three increased repurchase by 8 per cent and recommendation by an astounding 115 per cent.

If marketing is shifting towards data analytics and smart software, could the future of sales lie, not in giving the customer advice, so much as helping them feel good about the decision both before and afterwards?

The authors comment: “This approach is especially foreign to marketers… Often what a consumer needs is not a flashy interactive experience on a branded microsite, but a detailed exchange with users about the pros and cons of the product, and how it would fit into the consumer’s life.” By contrast, the direction that marketing is taking is to focus on decision science, big data and statistical analysis.

This is not to denigrate the huge potential for the intelligent application of big data in marketing and the insights it can provide into the customer journey. Improved data can bring us relevant, timely marketing in place of junk mail; it can provide information in real time through programmatic advertising and so on, and can even be used to offer live price adjustments.

Predictive intelligence

In fact, big data means marketing can predict things about us that we may not even know ourselves. An amazing case was reported in Forbes in February 2012: based on her purchasing patterns, a supermarket had begun to send a young shopper marketing offers for baby items. The girl’s father lodged a complaint, but withdrew it two days later when he discovered that she was indeed expecting a baby. As our ability to collect and analyse data increases, we can expect to see far more predictive intelligence personalising our marketing and advertising.

But, at the end of the day, we are all still human and our need for reassurance is strong. Buyers have a strong predilection to seek advice from strangers before a purchase. Some 69 per cent of us seek advice from others before buying, rising to 81 per cent in the 18 to 34 age group, according to a 2015 Mintel survey. And 54 per cent of people would even buy a product with negative online reviews, if recommended by someone they know; a finding that speaks to the powerful effect that others have on our opinions and decisions. We are also affected by buyer’s remorse, the need to justify our purchases to ourselves, as seen in the growth of “haul videos” displaying recent purchases on YouTube.

Major shift

The implications of this for sales are rather intriguing. If marketing is shifting towards data analytics and smart software, could the future of sales lie, not in giving the customer advice, so much as helping them feel good about the decision both before and afterwards? That could lead to a major shift in the way salespeople are trained, with far less emphasis on targeting, planning and closing the sale, and far more on psychology and decision-making. In turn, this might attract different kinds of people to sales roles, with emotional intelligence and empathetic behaviours prized above presentation and negotiation skills.

Plus, we may see the end of rewards based on sales numbers or quotas; instead we might find salesperson performance measured by relationship quality indicators such as how content a customer feels with their purchase, their propensity to rebuy and their willingness to recommend to others.

What does all this mean for investment in marketing and sales? In marketing, we can expect growing investment into marketing technology and systems, which are likely to become even more important in feeding us the right kind of communication and information just at the point where and when we need it. But, for the human side of things, it looks like sales will have a role to play for many years to come.

Customer retention