Sophie Atherton was on a train when she learnt that sensitive personal information about her had been leaked by her university to hundreds of fellow students. “It was devastating,” she says. “I just burst into tears. I felt like my life was on show for my entire department to see.”

Ms Atherton, 22, is a student at the University of East Anglia (UEA) in Norwich. Earlier this year the university sent an email by mistake to all American studies students. It contained personal data relating to 191 students, including Ms Atherton, with details of health problems, family bereavements and personal issues. It listed extenuating circumstances in which essay extensions and other concessions were granted.

When the mistake was discovered, the university sent a second email asking for the original email and attached spreadsheet to be deleted without being opened. UEA has apologised to all students affected by the breach and says safeguards have been put in place to ensure it does not happen again.

But for UEA students like Ms Atherton the harm has already been done. The fact that the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), the regulatory body, decided to take no action against UEA has not helped. “It is disappointing, to say the least,” she says. Ms Atherton has been having counselling and is considering legal action against the university.

Employees at Morrisons are already taking legal action against the supermarket chain after their personal details were leaked by a former colleague. In a landmark case, more than 5,500 staff are seeking compensation for the “upset and distress” caused by the company’s alleged failure to keep their information safe. Their data was leaked by Morrisons’ former auditor, Andrew Skelton, who has been jailed for eight years. The supermarket, awarded compensation of £170,000 against Skelton, denies liability for the leak.

Both examples illustrate the range of information that ordinary people entrust to organisations and the impact a data breach can have on their lives. It’s not just about bank account details being exploited by online fraudsters, but also about sensitive information that can cause distress if shared with the wrong people.

Our digital footprint contains information about every aspect of our lives, spanning the emails we send, the websites we visit and the information we submit to online services. Unless we can have confidence that this information will be held securely and used in an appropriate manner, we cannot have trust in the daily online engagement central to modern life.

In recent years there has been an exponential increase in the amount of information we share online, which is why the European Union has taken steps to update regulations concerning the management of personal data. The General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR, comes into effect in May 2018 and represents the biggest shake-up in more than 20 years of the way your personal information can be used by government, businesses and other organisations.

Although the UK is in the process of leaving the EU, organisations must comply with GDPR to be able to have any dealings with counterparts based in the EU. Its provisions in the UK will be covered by a new Data Protection Bill, which includes almost every aspect of GDPR with some minor changes.

Which are the main changes made by GDPR? It gives individuals more control over their data. Organisations will have one month to respond to requests about information held and must carry out the investigation for free, with the current £10 charge scrapped.

Organisations will be more accountable for their handling of personal information. Under GDPR, the “destruction, loss, alteration, unauthorised disclosure of or access to” personal data has to be reported within 72 hours. To put that into context, Yahoo! recently disclosed a data breach dating back to 2013, while Equifax, the credit report group, took several weeks to admit a data breach affecting more than 140 million people.

European Parliament building in Strasbourg; despite the UK’s impending exit from the European Union, organisations must still comply with most aspects of GDPR

GDPR gives national regulators, including the UK’s ICO, powers to impose substantial fines on organisations for security breaches. The most serious offences could receive fines of up to €20 million or 4 per cent of a firm’s global turnover, whichever is greater, and less serious offences could result in fines of up to €10 million or 2 per cent of a business’s global turnover.

The new EU regulations will have a varying impact on businesses and organisations, for instance not every company will require a data protection officer. In the UK, the ICO has published a 12-step guide to help organisations prepare for the start of GDPR.

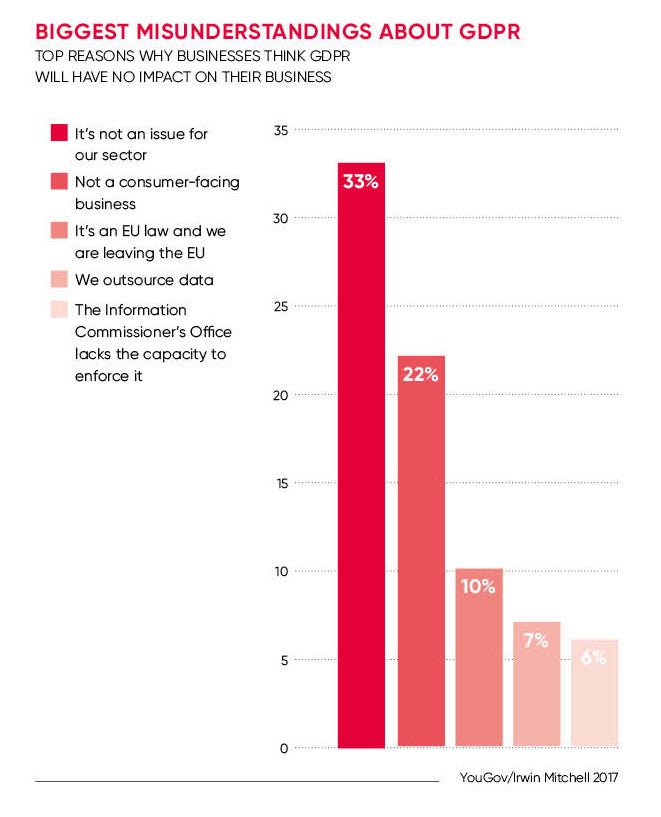

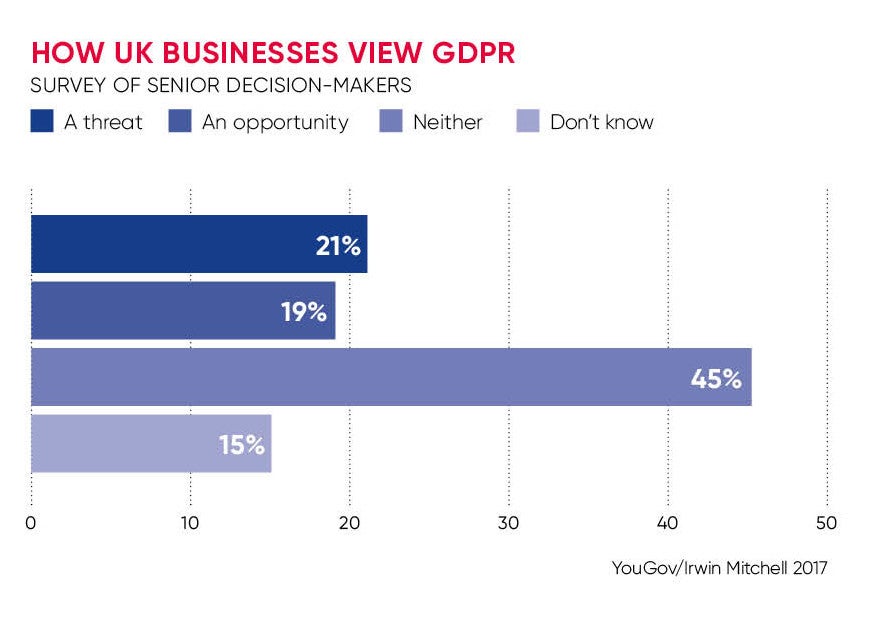

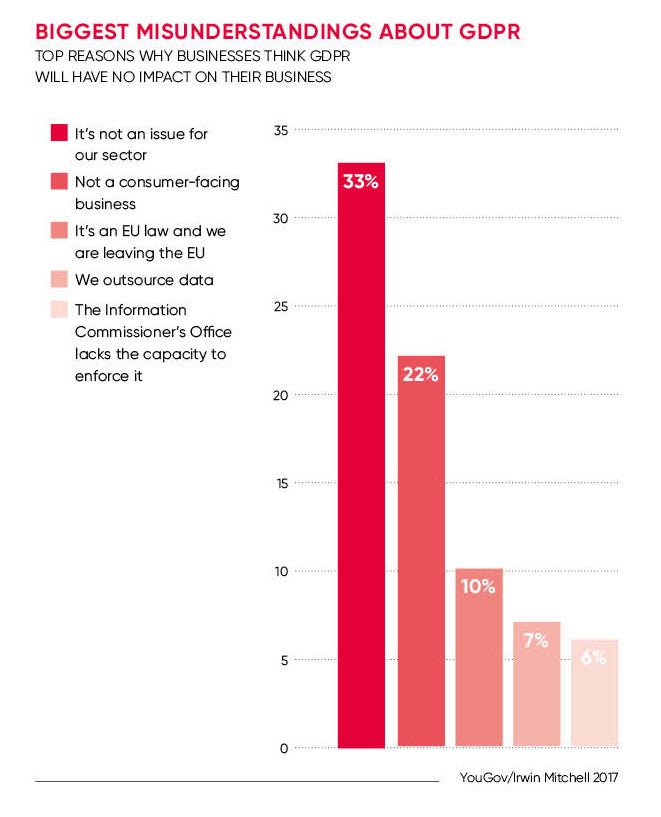

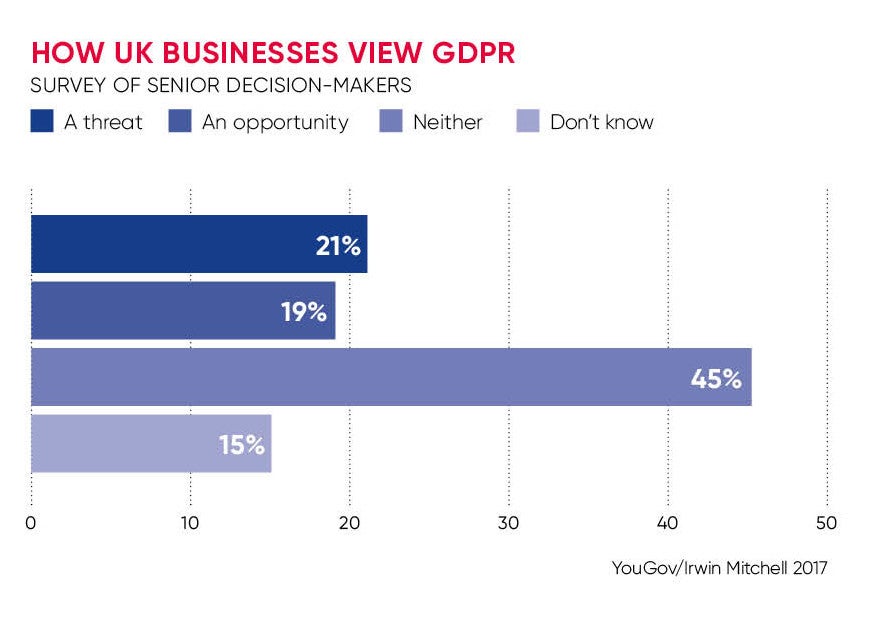

Many businesses are treating GDPR as another regulatory burden imposed by Brussels and are spending large sums of money to ensure they are compliant, and little more. Some are ignoring the looming regulation altogether. Yet GDPR is an opportunity to reset customer relationships at a time when trust is fragile.

Businesses that earn and retain trust will have far more customer data than less-trusted rivals, giving them a significant competitive advantage

Until now, businesses have often exploited data in the most aggressive way, collecting and using it for advertising or selling to third parties with little regard for the people involved. But GDPR is designed around trust and consent, with consumers able to withdraw their consent for a business to use their data. Businesses that earn and retain trust will have far more customer data than less-trusted rivals, giving them a significant competitive advantage.

GDPR also creates an environment that encourages the development of new customer experiences and products that will incentivise consent to the benefit of consumers. Strong data protection is a critical enabler for enhanced service offerings and digital commerce. Regulations that assure consumers they can trust vendors make for a positive outcome because they encourage consumers to do more business.

Research by KPN, the Dutch telecoms operator, shows that higher customer confidence in data security increases the amount of data they are willing to share. This information can be used to improve and target offerings. At the same time, consumers are likely to shun companies that they regard as careless with data.

Companies such as banks, retailers, telecoms operators and other consumer-facing companies amass huge amounts of personal data, which is increasingly seen as essential for competing in the digital era. But data also comes with responsibilities and significant risk. To maintain trust, companies need to assure customers that their data will not be stolen or abused. When that trust is violated the reaction is swift and devastating.

Preparing for GDPR can be a catalyst for taking the necessary steps to build strong digital capabilities, including innovation in customer master data management. With this in mind, the McKinsey consultancy suggests that GDPR has the potential to boost digital business throughout Europe, by making it easier to operate across borders by harmonising national data protection regulations.

With GDPR just six months away, organisations need to act now. The new regulation is an opportunity to put customers at the heart of business. If customers can see the benefit to them that their data is enabling, then trust and data accessibility will both grow.