GM is everywhere – not in the sense of fields and foods, but in public debate and the press.

Genetically modified organisms (GMOs) have been championed in the fight against the threatened “banana apocalypse” by fungal diseases, but challenged on safety grounds by the Norwegian government.

Engineered to help tackle vitamin-A deficiency, “golden rice” has been heralded as both a potential lifesaver by Danish author Bjørn Lomborg and a hoax by Indian environmentalist Vandana Shiva.

Biotech giant Monsanto has been seen holding open-house on the social networking website reddit, but heard under attack on the new album by Neil Young. Like it or loathe it, you cannot ignore it – GM makes news.

However, to have the issue front and centre in the agriculture and food debate is more hindrance than help, argues Peter Melchett, policy director at the Soil Association.

“GM is a huge distraction. At best, pro-GM campaigners claim they have a solution to one or two problems,” he says. “The technology cannot deliver integrated solutions to the range of challenges facing farming – climate change, hunger, loss of wildlife, poor animal welfare, soil degradation, and all other environmental and human problems caused by industrial agriculture.”

This tendency of GM to hog the public agenda is also a source of frustration for Danielle Nierenberg, president of Food Tank. “The thing that happens when you are talking about GMOs is the issue itself takes up all the oxygen in the room,” she says.

What troubles her more, though, is lack of progress. “My concern is that investment and research into GMOs has been going on for more than 20 years now and we still have about a billion people hungry,” she says. “We are still grappling with the same challenges we were grappling with 40 years ago. GMOs haven’t lived up to their promises.”

One key media battleground at present is the issue of the use of chemicals, with a case for GM made by Professor Jonathan Jones, of the Sainsbury Laboratory, in Norwich. He points out: “Already, there has been a vast reduction in insecticide applications worldwide. Over 400,000 tons of insecticide – nerve poisons – have not been applied thanks to GM.”

While Professor Jones acknowledges that usage totals for certain herbicides have gone up, particularly glyphosate, (a hot topic at present, with its own hashtag in hourly use on Twitter), he suggests this is because of their being substituted in place of what he describes as “nastier” alternatives.

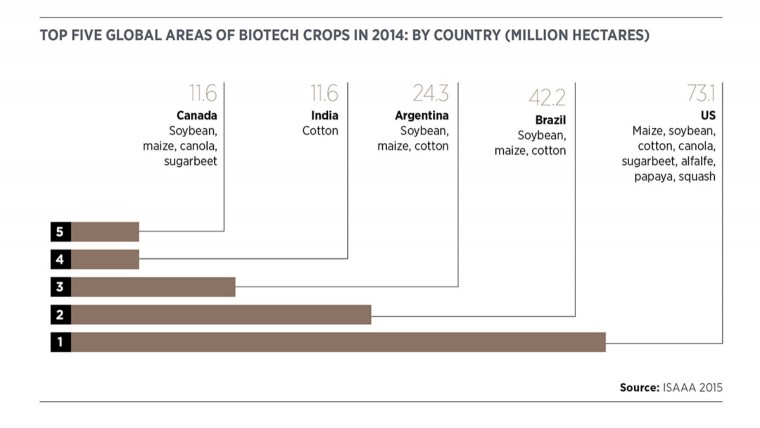

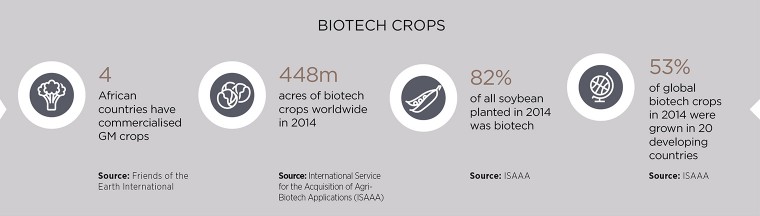

Forecasting reductions in fungicide applications from next year, when the potato blight resistance gene he cloned is deployed commercially in the United States, Professor Jones also tips Brazil for the country to watch, as biotech inputs begin eating into $1 billion-worth of fungicide applications used annually to control soybean rust.

This has to move to being an issue of social justice or the poorest of the poor will continue to suffer needlessly

He is at pains to place GM in context. “An important general point is that GM is just a method, not a thing, and it can be deployed to address many different agricultural problems, but only if there is a cost-effective business model for either private or public-sector actors,” he says.

For Rich Kottmeyer, senior vice president at Cheetah Development, getting the numbers to add up constitutes the day job, working to make smallholders investible. Mr Kottmeyer contends it is not just a matter of the total global shortfall in future food production that makes GM a must-have, but how the figures break down geographically. “Productivity gains are very uneven,” he says. “Sub-Saharan Africa is projected to reach only 13 per cent of food needs. If we don’t use all tools and techniques, we must be comfortable with an outcome of hunger and malnutrition that could have been prevented.”

In Mr Kottmeyer’s analysis, willingness to embrace modern practices, including GMO, approaches a moral imperative. “The gap between agricultural ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’ is astonishing. Data clearly shows that it is the poor smallholder farmer that suffers the most from a lack of technology access,” he says.

“Ironically, the hungry bear the brunt of the fight and have little voice. This has to move to being an issue of social justice or the poorest of the poor will continue to suffer needlessly.”

For Ms Nierenberg, though, GM is part of an ag-tech image problem. “When people think technology, they think GM and they can’t think anything else. It makes technology seem bad and technology isn’t bad in agriculture,” she says. “If we are concerned about figuring out the challenges – whether climate change, hunger or protecting the environment – we need technology to do that.”

The debate about the urgent need for technology in agriculture is perhaps strongest in relation to Africa, where food insecurity is highest and GM slow to gain acceptance.

Reality for the have-nots there is stark, concludes Richard Munang, Co-ordinator of the United Nations’ African regional climate change programme. “In Africa, the major vulnerability is climate driven – 25 per cent go to bed hungry, more than 200 million suffer chronic to severe malnutrition, which also accounts for over 50 per cent infant mortality,” says Dr Munang.

“In the face of climate change, 11 to 40 per cent declines in productivity of key staple foods in the continent are projected, implying a 25 to 90 per cent increase in the undernourished by 2050.”

Led by the UN Environment Programme and acknowledged by the African Union, the call is for policies of ecosystem-based adaptation. The role for GM is still up for negotiation, backed by the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa, but facing political resistance and public unease.

With strong opinions across continents both for and against GMOs, media controversy is seldom far away. In the face of an impending global food crisis, healthy debate about the future role of technology in sustainable agriculture is desirable, even essential. However, associated delay and disruption is not.

Against the clock, the question to ask is not perhaps whether GM is the answer, but whether GM is the question.