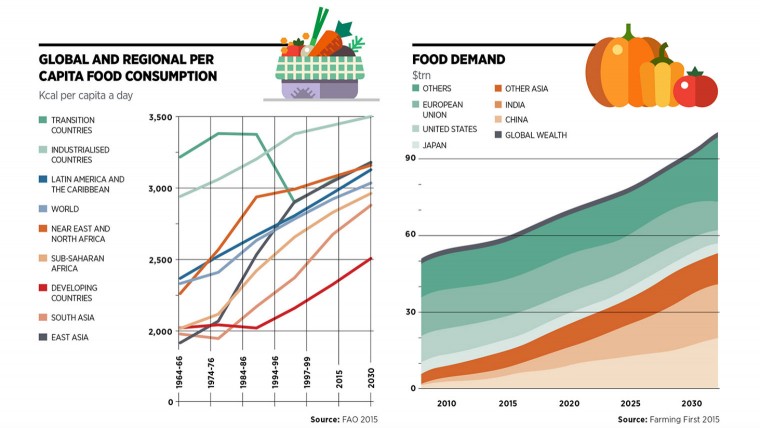

Forecasts predict that as world prosperity widens so the demand for beef, lamb and pork will increase.

Farmers in the UK will have to make life-changing decisions as farming is not like running a factory where changing markets can be dealt with comparatively swiftly. In contrast, agriculture is governed by the seasons and, therefore, has to take its time, governed by uncontrollable elements, the state of the soil and diseases that can affect animals as well as crops.

But changes are already taking place as the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB), representing farmers and food producers of meat to potatoes, cereals and dairy products, sees in export patterns around the world.

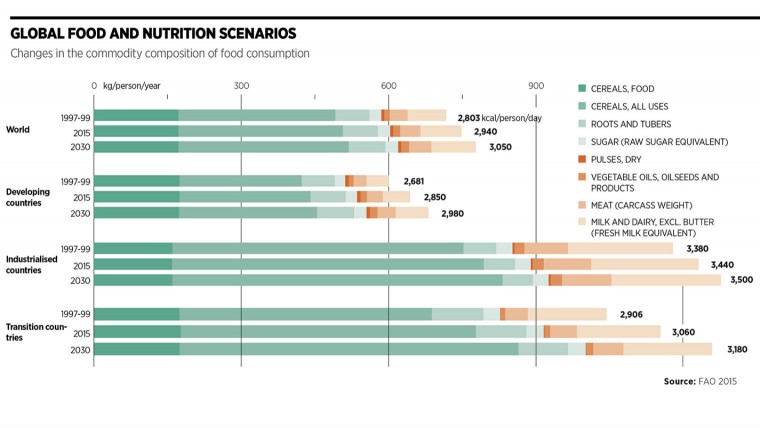

Eating habits are changing for various reasons, but largely due to rising standards of living. This still leaves millions poor who, ironically, are often the ones providing the better off with their food. But in general more money in pockets internationally has changed the eating habits of the world, and will ultimately benefit growers and producers.

More money in pockets internationally has changed the eating habits of the world, and will ultimately benefit growers and producers

The biggest change is an ever-growing demand for meat. As Stephen Howarth, AHDB’s market specialist manager, notes: “The trend for meat consumption is an upward one.” His organisation joins DEFRA, the government department representing food, farming and the environment, among much else, in attending trade shows in the Far East to find new export markets far from the guarantees of the European Union.

A success story is Macau in China where UK farmers were this year given the go-ahead to export beef and lamb. Macau’s important gastronomy sector opening up to UK meat is important as our farmers aim for the niche luxury market.

Mr Howarth has other examples. “The Thai government is keen to cater for quality food and drink for their 27 million tourists each year,” he says. “The UK export beef, pork and lamb to Singapore, which is seen as one of the most attractive markets in the world for premium meat and food products; the country produces little food and needs to import it.”

These market conditions are repeated in Hong Kong, where one of the largest food and hospitality shows in the region was held earlier this year. Earlier this month, environment secretary Liz Truss announced that global UK pork exports had rocketed by 44 per cent in the last five years, bringing in £214 million a year, with China providing our top growing market.

Wagyu beef from Japan and Australia, and premium offers from North America and Australia, are popular in the high end of the Hong Kong market, which accounts for nearly 70 per cent of the food consumed there, while Brazil and other suppliers provide large quantities of beef to the mass market.

But it is the niche markets that farmers seek out, because the prices they receive are at premium levels.

Mr Howarth says this year’s mission was to sell beef, lamb and pork to the Far East, notably Japan and South Korea, and to India, but draws attention to the need to address religious requirements. Large areas of the world, and many international airlines, demand meat killed in the halal manner, which currently favours lamb from New Zealand and Australia, the world’s largest suppliers.

A visit to Waitrose in Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates, underlines the global nature of today’s market, with little from the UK, but Australian and American beef and fruit dominating the shelves, along with New Zealand lamb and potatoes from Ireland.

On the outskirts of Dubai, where genetically modified (GM) foods are banned on environmental grounds, there is the International Center for Biosaline Agriculture (ICBA). Here experiments are taking place to see which crops can thrive on the least water, to feed countries that are or will be affected by climate change. Research crops in the surrounding fields are cultivated to test which plants can live on saline soil. In the Arabian Peninsula, where the environment is harsh and most soils are saline and poor in nutrients, only a limited number of crops can be grown successfully, the researchers say.

It may be best known in the UK as a dish served by up-market chefs, but quinoa could solve many problems as a high-protein grain crop for wherever temperatures are high and water scarce. It is tolerant to salt water and is grown in the salt beds of Bolivia and northern Chile. Seeds can be used as a breakfast cereal, to make soup, brew beer and as animal feed. It tolerates drought and has a low water requirement. It is thriving on the ICBA experimental soil.

Dietary changes worry researchers at the Netherlands-based Water Footprint Network, who feel that the projected increase in the production and consumption of animal products is likely to put a further strain on the globe’s freshwater resources.

In a recent report, the network points out that animal products per ton generally have a larger water footprint than other crops. The same is true when the water footprint per calorie is measured. Their researchers found that the average per calorie for beef was 20 times larger than for cereals and starchy roots.

So how could changes in diet and greater demand for meat, which put immense pressure on the world’s diminishing water supply, be met? Dr Ashok Chapagain, the Water Footprint Network’s science director, says this can only happen through education, which could take at least 30 years. But, optimistically, he told how he had spoken to children at an Austrian primary school about water shortage, and that they were already aware of the water footprint of the food in their daily lunch boxes and had changed eating habits to reduce the footprint.

The other big threat to stability caused by the expanding global market for food is land-grabbing. This is the practice of richer countries taking over the land in poorer countries to grow themselves food for the future.

Oxfam’s land rights policy lead Kate Geary explains: “Cheap land, high food prices, speculation and drivers such as European biofuels targets have sparked a rush for land with Africa at the bullseye. The scramble for land has seen food crops being exported to richer countries far away or being used for fuel instead of food – at the expense of local communities.”

This has led to thousands of people losing their land, their homes and their way of life without consultation or compensation. However, it can be negotiated legitimately. China, for example, has taken over land in Australia and New Zealand with the full co-operation of both governments.