We’ve never been more in control of monitoring our health. From wristband step and heart-rate trackers to weighing scales that monitor body fat, wearable and self-monitoring medical technology is changing the way we think about our own biology. Soon there will even be implants with sensors, which can measure blood data in people with diabetes.

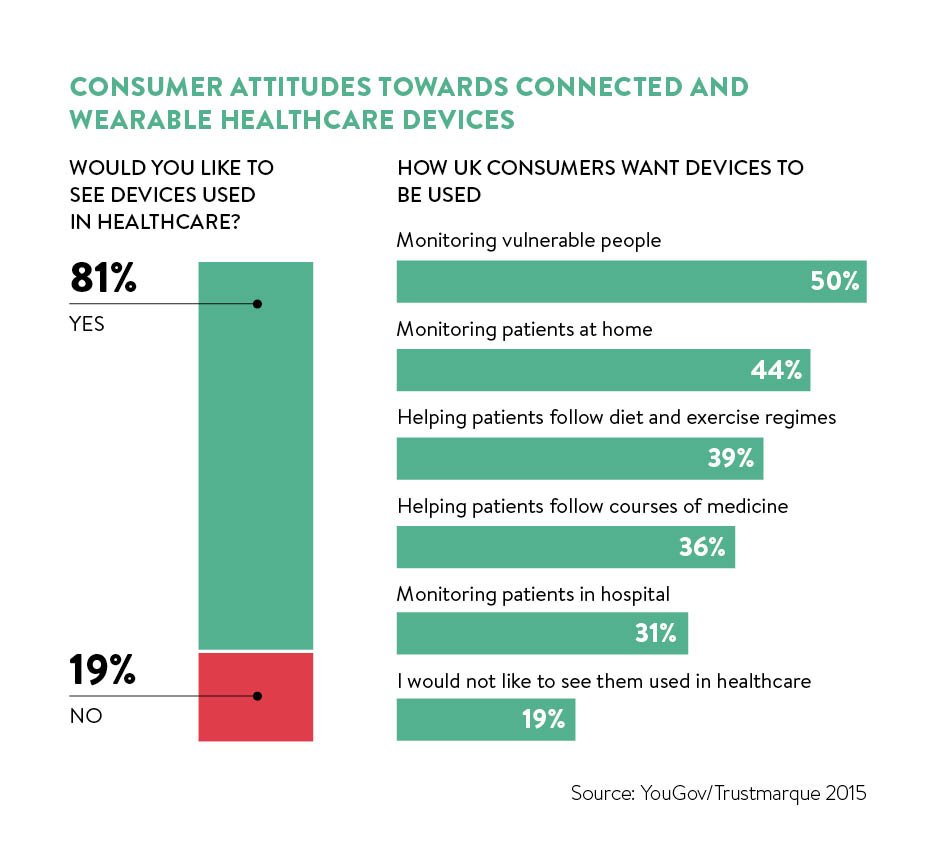

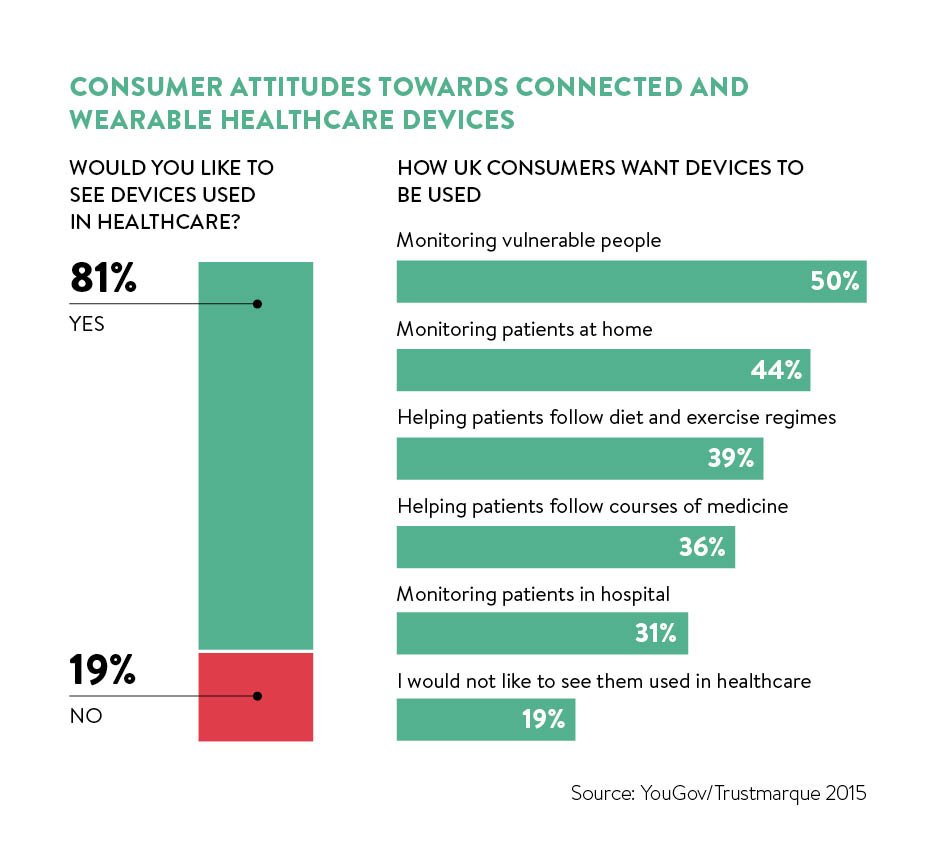

This high-tech approach to healthcare is popular too. According to a recent survey by software service company Trustmarque and YouGov, 81 per cent of respondents said they would like to see more connected and wearable devices used in healthcare, with half of respondents saying they thought wearables were potentially most useful to monitor vulnerable people.

Cost savings for the NHS

Collette Johnson, director of medical at electronics consultancy Plextek, believes the use of self-monitoring devices has enormous potential and could help the NHS save at least 60 per cent on the average cost per patient. Crucially, she thinks, the public is ready for it.

“Wristband monitors like Jawbone and Garmin vivofit are helping us become more aware of how our bodies work,” she says. “They have taught us to be more aware of what is normal for our bodies.

“And in a patient with a chronic condition, such as diabetes or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a wearable monitoring device might alert them earlier to a change in their health which needs medical attention. So wearables can help patients engage with the medical community sooner.”

Cédric Hutchings, vice president for health at Nokia Technologies, agrees. “The greatest benefit from wearables is in chronic disease management through empowering the patient,” he says.

Withings Body Cardio, developed by Nokia Technologies, uses pulse wave velocity to monitor weight, BMI, body composition and heart rate

The key, Mr Hutchings says, is finding ways wearables can be part of everyday life for users. For example, Nokia has just launched a set of scales, called Body Cardio, which use pulse wave velocity (PWV) measurements. This means users can log accurate measures of weight, body composition (fat, muscle, water and bone mass), standing heart rate and PWV, which is a key indicator of cardiac health and associated with hypertension and risks of cardiovascular incidents. The scales, available from Apple, are Nokia’s most advanced product to date.

Developments in the internet of things (IoT) – the network of physical devices, vehicles, buildings and other items embedded with electronics, software, sensors and network connectivity, enabling them to collect and exchange data – are allowing healthcare to be administered more remotely.

Roman Chernyshev, senior vice president of healthcare and life sciences at global technology consulting firm DataArt, says: “It is a matter of time before medical devices collect continuously vital data from millions of patients around the world in real time and simultaneously compare them.

“These developments will change how diseases are diagnosed. Medical conditions will be predicted as a result of data and constant monitoring of health information.

“Technological advancements will result in healthcare being everywhere, although it will be almost invisible. One IoT device that is being developed will be used to prevent metabolic diseases such as diabetes. An implant will constantly collect and analyse blood data from diabetes sufferers and independently inject insulin without the need for human interaction or prompting.”

Potential target for cyber crime

But the experts acknowledge there are concerns over self-monitoring devices too, not least from the public. Trish Birch, global healthcare consulting practice leader at IT consultancy Cognizant, says: “The amount of data being collected via IoT in this way is growing quickly, with the market expected to be $5.8 billion in 2019, according to analyst firm IMS.

“However, consumers are sceptical of sharing health information, with only 32 per cent sharing information collected by apps with their providers.”

“However, consumers are sceptical of sharing health information, with only 32 per cent sharing information collected by apps with their providers.”

Cyber crime is also a worry for some, not unreasonably says David Emm, principal researcher at security software experts Kaspersky Lab. “Medical devices are a potential target for cyber attackers,” he says.

“In the case of medical devices and wearables, such an attack could be highly targeted; for example, altering the dosage or combination of medicines to cause harm to a specific individual, or to damage the reputation of the company that has developed the device or the medication.

We will be able to filter and aggregate information better, generating insights and outcomes

“And fixing flaws in medical devices may be far from easy. For example, with pacemakers, if a vulnerability is found then it may not be possible to roll out a patch, as you could for a smartphone or PC. So it may be difficult to secure these devices once implanted, as the whole thing may need replacing – a costly and logistically difficult process.”

Ms Johnson at Plextek also warns that for some, self-monitoring devices can induce competitive urges which are not healthy. “We don’t want people losing weight, for example, and going too far. The interface has to be able to warn, in the right way, when enough is enough,” she says.

“There is also the danger of creating a new worried well. We don’t want people to become alarmed.”

And there has been a backlash in the United States against that type of tech. Last year the Federal Trade Commission fined two companies which created apps promising to “diagnose” skin cancer. In January, a fraud class action lawsuit on behalf of consumers nationwide was launched against Fitbit Inc. over complaints that certain of its heart-rate monitors failed to measure user heart rates accurately.

“The industry must be responsible,” says Ms Johnson. “It is not good enough to give consumers personal data without context. We need to make it clear that self-monitoring devices can show you only what is normal for you.”

This will be even more important, she believes, in the future as self-monitoring moves into the home connecting families and collecting community data.

The solution for designers may lie in creating products which are easier to use and interpret. Nokia Technologies’ Mr Hutchings says: “As we get more sophisticated, we will be able to filter and aggregate information better for patients, their doctors and nurses, generating insights and outcomes. But there is work to be done on the user-interface.”

He compares it to the latest cars. “There are hundreds of sensors in a modern car, but they don’t all provide data for the driver. Indeed, the dashboard offers quite simple information.

“Our scales are the same – they won’t overwhelm you with biometrics. They are not going to give you a full diagnostic picture every time you use them, but they may alert you to a trend worth talking to your doctor about.”

Cost savings for the NHS

Potential target for cyber crime