French philosopher Victor Hugo said, roughly translated, that there is nothing more powerful than an idea whose time has come. The remarkable thing about this is its emphasis on timing – some ideas must wait for a trigger-event before making their debut.

Quite often a good one floats around the cosmos for years without impressing. Then the stars align, the idea is trialled and it transforms from a rudderless notion into something tangible, valuable and sought after.

One minute we all wonder who would want it, the next we’re equally perplexed as to why we didn’t demand it sooner. This is true of many innovations, from seat belts to touch screens to the smoking ban, which were once considered undesirable, but today are undisputed.

One such idea has become known as the sharing economy, which put down roots soon after the widespread adoption of social media. It allows people to bypass the rigid structures of capitalism in which consumers buy and producers sell, and jiggles them about, blurring who does what.

Nothing new

There is nothing new about it, nor is it particularly inventive, in fact it’s recycled from the bartering economies of yore. It simmered for decades in car boot sales, babysitting circles and neighbourly exchanges of lawn mowers and cups of sugar.

Then globalisation and mass communications arrived, blending to create a platform upon which sharing has risen from the small, parochial and ad hoc, to something truly international, organised and status quo-obliterating.

Founded only eight years ago, Airbnb has kicked the legs from under the hospitality industry

Leading this shake-up are the new business titans like Uber and Airbnb whose universal appeal and colossal sales belie their tender years. They are the child prodigies in short trousers beating aged grand masters at their own game.

Founded only eight years ago, Airbnb has kicked the legs from under the hospitality industry. Its rise was predicated on a shift in the mindset of property owners. Ten years ago your home was your castle; now, for many people, it is a fantastically valuable asset to sweat.

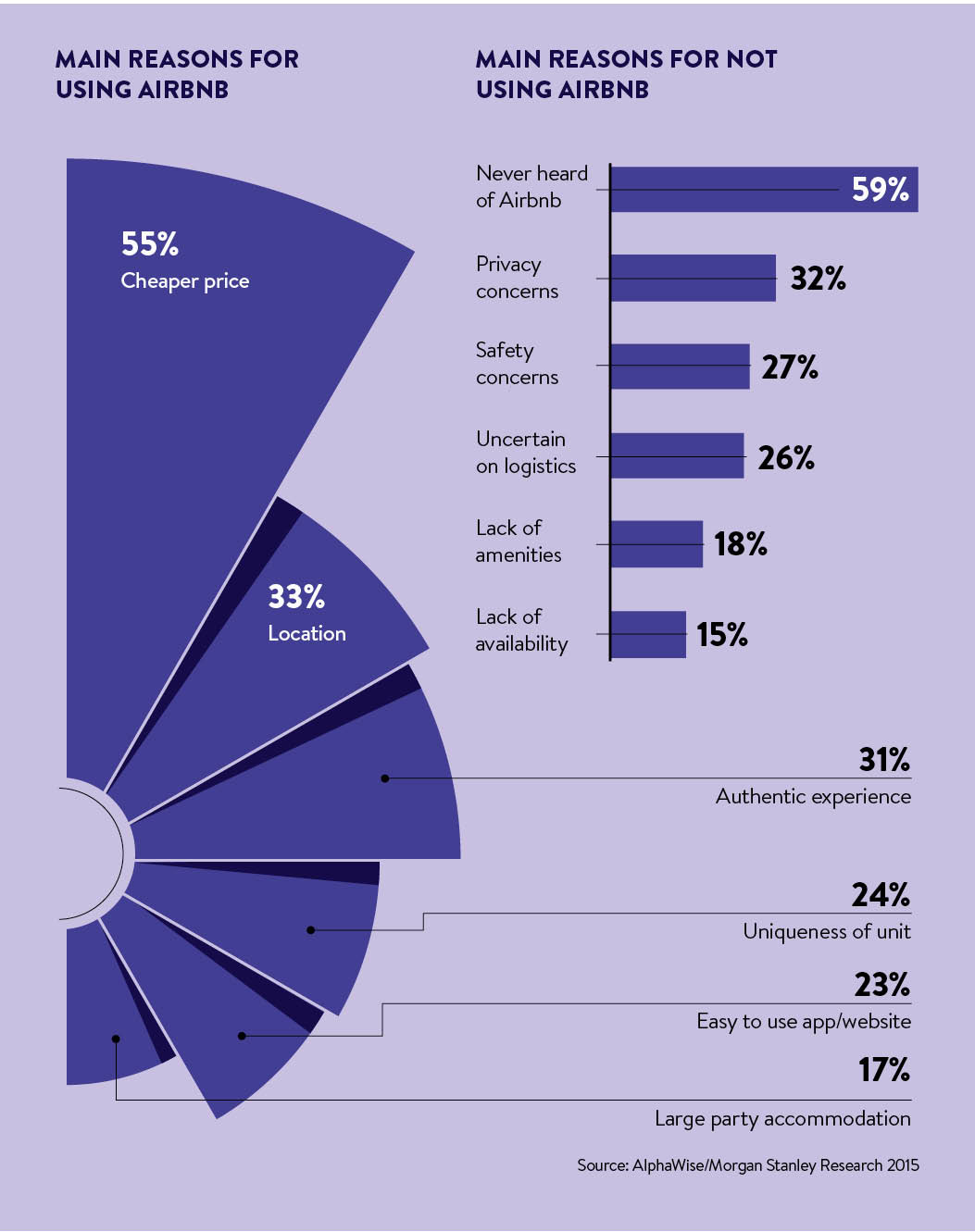

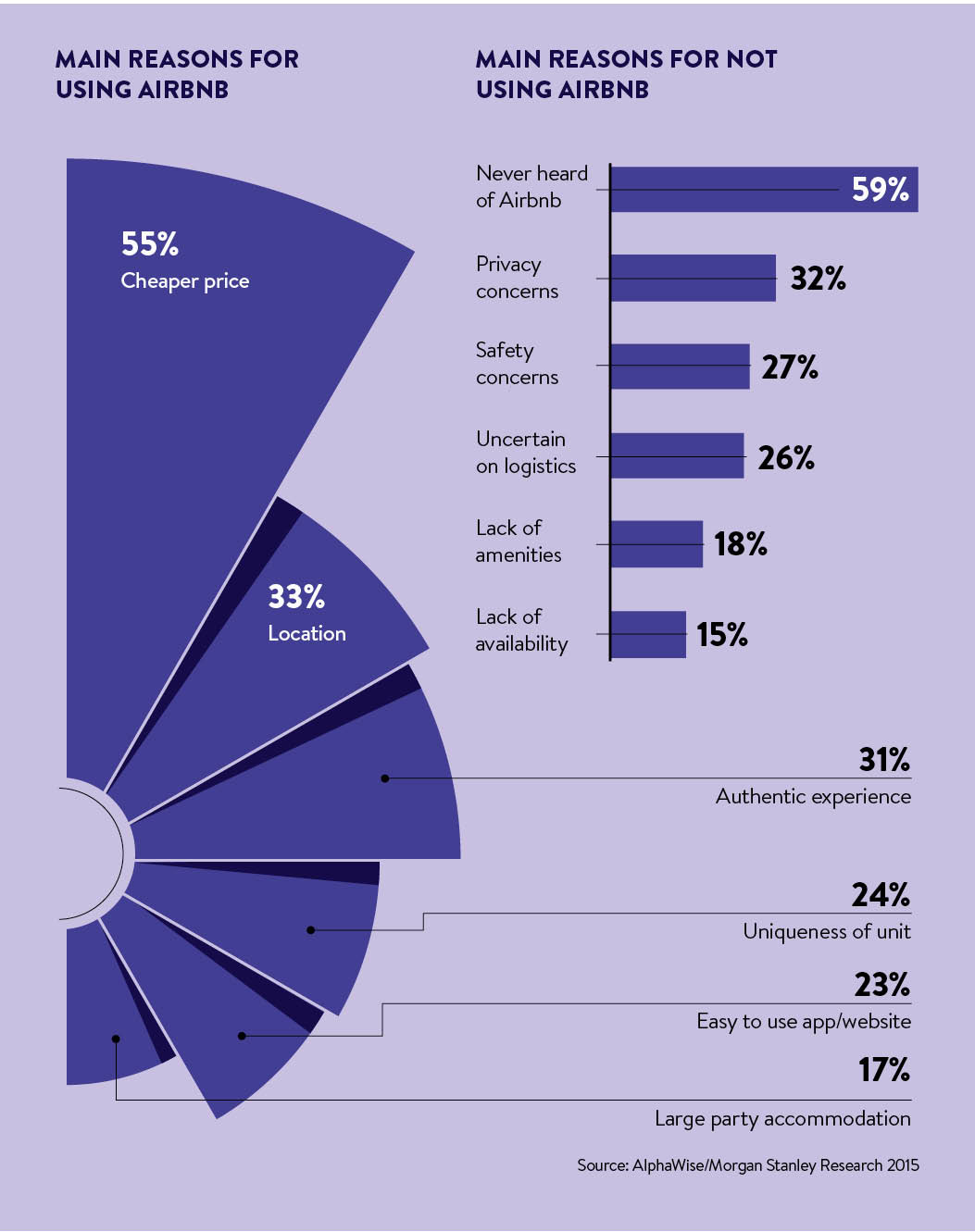

“There was an economic need to share an underutilised asset like a home or a room within a home,” explains Adnan Saulat, general manager at technology services company Mindtree. “Once there was enough liquidity and branding in the market, a tipping point was reached that drew many people towards it.

“With the advent of social media, it became very easy to trust others. It was now OK to share rooms with complete strangers and buyers were now willing to sleep in other people’s homes. Reviews, photos and social media profiles help create the trust initially. It is further strengthened if the seller has provided ample information about the property. Community plays a very important role in helping the circle of trust that forms between individuals.”

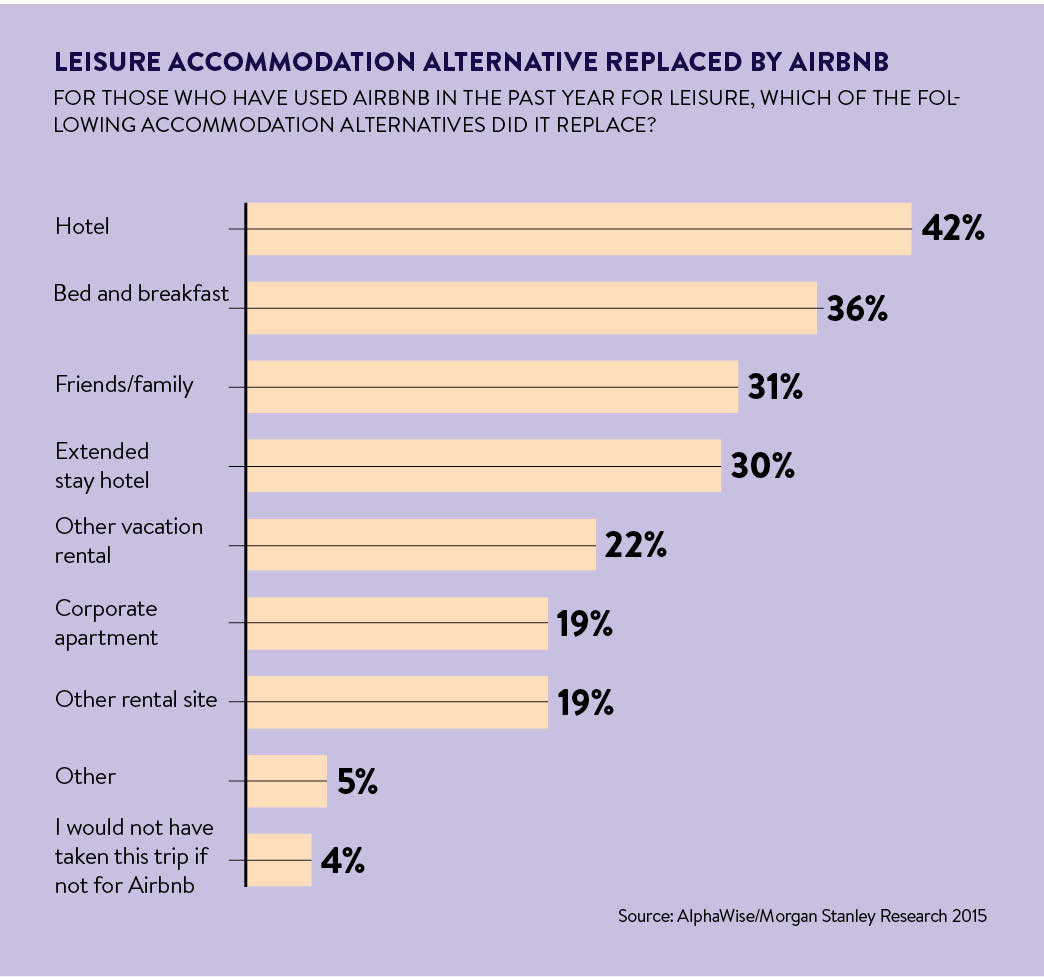

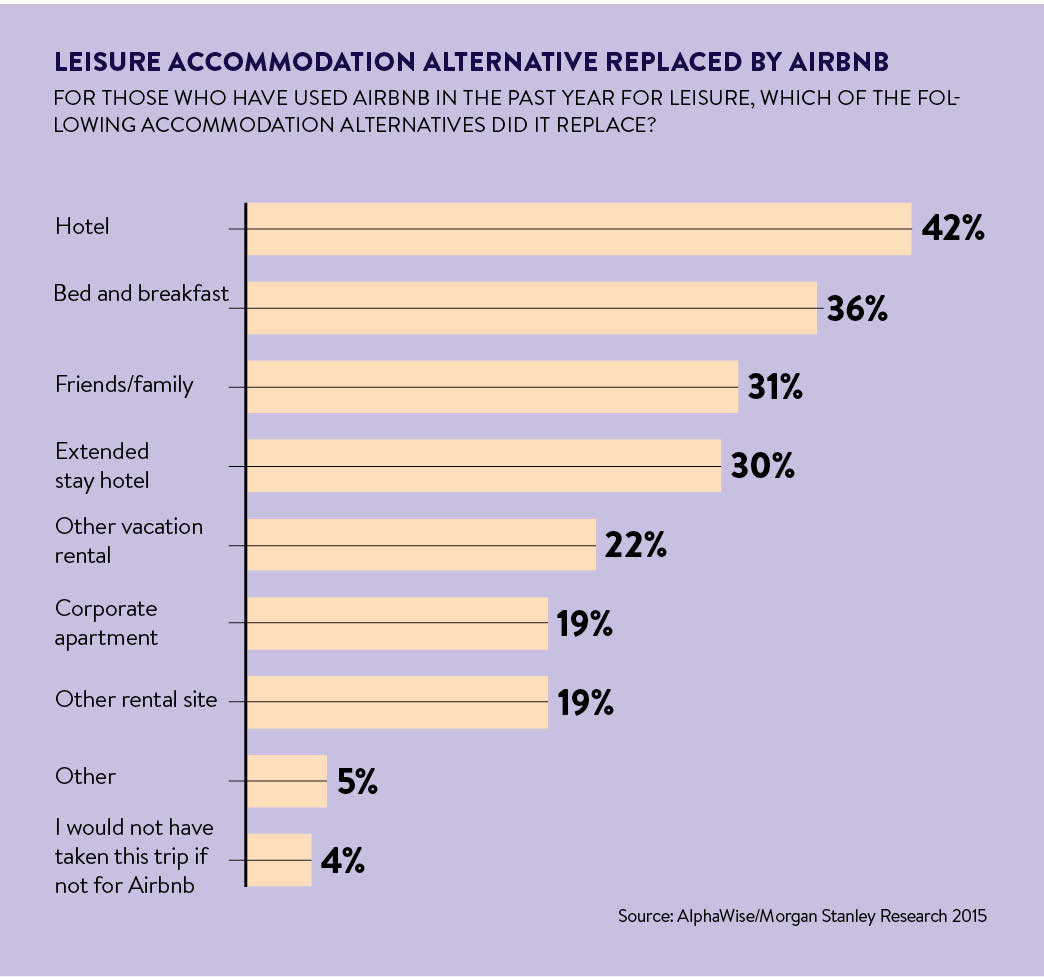

Hotel chains that for so long operated on a level playing field with challenges and opportunities they understood, are now ripping up business plans and devising ways to co-exist with this enormous new rival.

Airbnb attacks the end of the market that is undifferentiated and doesn’t add a lot of value: stars one to three. Luxury hoteliers have the firewall of customer service, which Airbnb doesn’t major in. But conveniently located, no-nonsense guest houses are directly in its sights.

The new service can beat them on customer experience. It plays up the notion that travellers want to holiday like a local, getting to the heart of a community instead of perched on its hinterland as a – the word sticks in the throat – tourist.

But chains like YOTEL, founded by Simon Woodroffe in 2002, claim to have a ready-made set of unique selling points that protect it from what Airbnb does best.

“Business travellers often require meeting spaces or shared working areas, which an Airbnb property is unlikely to provide,” says Jo Berrington, YOTEL’s vice president, brand. “Most Airbnb accommodations don’t offer the flexibility hotels can give such as around-the-clock check-in or free cancellation of bookings. Hotels provide guaranteed comfort and basic necessities free of charge, and most of all virtually instant communication for whatever you might need.”

Swerving regulations

There is another check on Airbnb’s fast growth, one which is common to many businesses in the sharing economy: regulation. Hoteliers complain, with some justification, that it holds a charmed position in the market. In most jurisdictions it swerves onerous rules rivals must comply with.

Hotels have to meet stringent health and safety standards which cost millions of pounds in fixtures, fittings, provisions and signage. As yet Airbnb makes no such commitment. There is also the question of legality where someone’s home is also their business; what are the implications for areas like tax and insurance?

A third bone of contention, particularly in places like London where residential property is in short supply, is the large profit margins of short lets. More Airbnb listings mean fewer homes to go around for local residents, equating to even higher house prices and rental values.

“In London, concerns have been raised that Airbnb is impacting the housing crisis, with landlords being accused of taking long-term lets off the market and promoting them instead as short-term holiday stays,” says David Ryland, corporate real estate partner at law firm Paul Hastings. “This may well encourage local government to take action given how sensitive and political issues around housing are in the UK currently.”

In the German capital Berlin, Airbnb has been subject to a partial ban such are concerns about its impact on the local economy, while other European cities have slapped restrictions on its use.

“Airbnb is under threat of regulation in cities around the world. It’s plausible that similar rules as those in Berlin could be implemented in the UK,” says Nakul Sharma, chief executive of Airbnb management platform Hostmaker. “In Paris, Airbnb pays tourist taxes and in Barcelona you need a licence to rent your property. These are other options for UK regulators which may impact growth.”

Nevertheless, Mr Sharma argues that demand for authentic, personal travel experiences will continue to fuel Airbnb’s appeal even after regulatory corrections come into force. He sees a gradual merging of hotels and homes, combing the professionalism of one with the experiences offered by the other.

And there is evidence to back up his claim. In April, global hotel group Accord acquired upmarket Airbnb rival Onefinestay for €128 million. The business provides a similar service to Hostmaker, offering a hands-on experience with fuller customer service.

And there is evidence to back up his claim. In April, global hotel group Accord acquired upmarket Airbnb rival Onefinestay for €128 million. The business provides a similar service to Hostmaker, offering a hands-on experience with fuller customer service.

“Branded homes are the future of the hotel industry,” says Mr Sharma. “Hotel chains are best placed to make this happen as they have the resources, reach and household name that would be needed. Collaborations between sharing-economy disruptors and big hotel groups would be no bad thing.”

Elena Lopez, managing director of fellow property management company My Property Host, agrees. “The traditional hospitality sector can learn a lot from the most successful Airbnb hosts,” she says. “Adding greater individuality to rooms, providing more informal communal areas and offering more personalised recommendations about the local area will all appeal to guests who value authenticity as well as a comfortable bed for the night.”

Like so many other industries impacted by new technologies and the ideas they help to facilitate, the hospitality sector is in turbulent waters. But with flux comes opportunity and companies will do well if they can adapt to evolving customer proclivities while walking the legal tightrope.

Victor Hugo was right. All powers in the world won’t be able to reverse the march of the sharing economy. Hotels must understand that it’s better to get on board than sit on the sidelines and dumbly watch as the opportunity passes by.

Nothing new