When Hollywood movie mogul Harvey Weinstein was accused of sexual abuse, the floodgates holding back generations’ of unreported harassment in the workplace, burst open.

The numbers are shocking. More than half of women in the UK (52 per cent) have experienced sexual harassment at work, a proportion that is higher still among young women, aged 16 to 24, at two thirds (62 per cent), according to research published by the Trade Union Congress (TUC) and Everyday Sexism Project in January 2016.

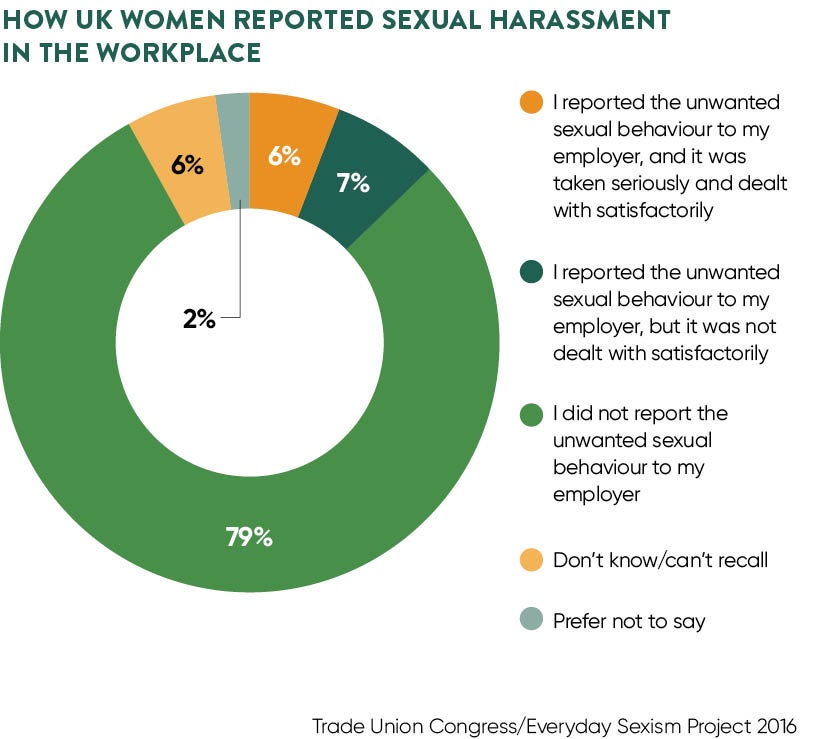

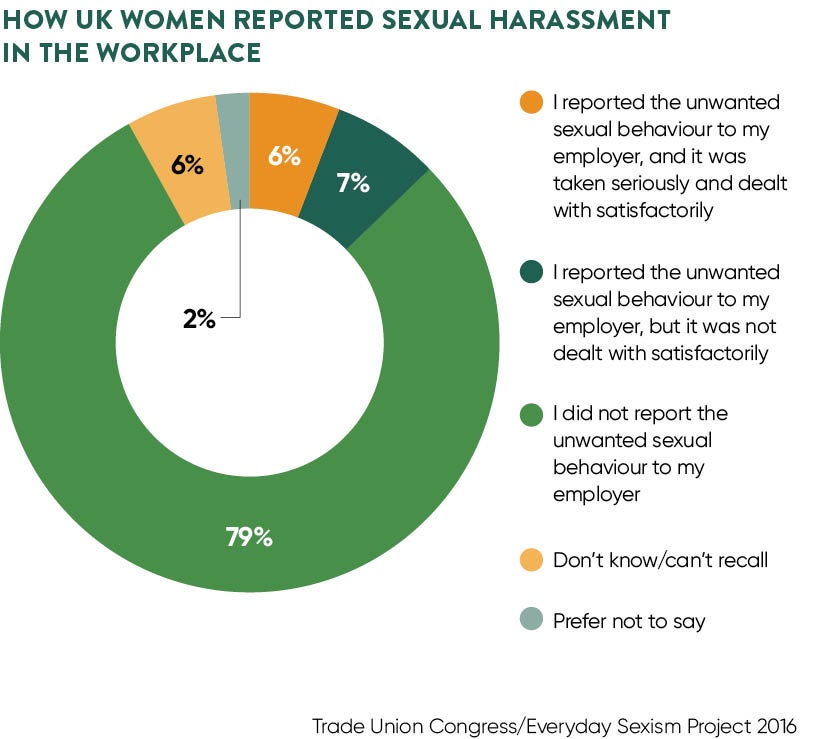

It is shameful that these findings are not new. The TUC report is almost two years old. “It is really a big problem,” says Scarlet Harris, TUC women’s equality officer, and there is a long way to go. Of the minority of women reported sexual harassment, very few saw a positive outcome. In almost three quarters of cases no action was taken and in 16 per cent the harassment worsened.

It does feel like there’s been a sea change in how willing women are to talk about sexual harassment

Ms Harris is cautiously optimistic, however, that social norms are beginning to change. “It does feel like there’s been a sea change in how willing women are to talk about sexual harassment. It feels as if it’s opened up a space to challenge some of the taboos surrounding it and get it out in the open,” she says.

What more can human resources do? While one in ten HR professionals were aware of formal sexual harassment complaints in their workplace, according to a recent YouGov survey, one in eight large employers also admit that sexual harassment in their companies goes unreported, a survey published by the Young Women’s Trust this September reveals.

HR’s primary objectives must be to create an environment where behavioural standards are high, where every employee feels a responsibility to maintain them, where employees feel free to report harassment, without the fear of retaliation or damage to their careers, and where allegations are taken seriously, addressed swiftly and where sanctions are appropriate.

The first step is getting the definition right, says Rachel Suff, employee relations adviser at the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development. “Employees must know what is expected of them,” she says. “Some will be surprised by the definition of sexual harassment in the Equality Act which is quite broad, but if HR and senior management are clear about the kind of environment they want to create, and what sexual harassment is and how it can manifest, it will not be difficult to draw up really clear guidelines and communicate them.”

This means addressing the kind of low-level behaviour that has sparked so much debate and confused incredulity from some quarters of the media. Is it really helpful, some have asked, to lump unsolicited compliments, innuendo and the odd sexual joke under the same blanket term that covers physical offences?

Unequivocally, yes, says Ms Suff. “You have to call this behaviour out for what it is, because not doing so is part of the problem. It doesn’t mean every allegation will result in the same outcome. In some cases a conversation could be enough, but that person should be made to understand that their comments fall within the spectrum of sexual harassment.’

Low-level harassment is a kind of slurry from which worse harassment can grow

Low-level harassment is a kind of slurry from which worse harassment can grow. “It often starts small, but if unchallenged it can build. It is insidious; before you know it, that’s the culture and that is what allows the worse incidents to happen. It breeds a kind of permissiveness,” Ms Suff says.

It is important for HR professionals to acknowledge that at its core sexual harassment is abuse of power. And Ms Harris and Ms Suff both suggest that it is more prevalent in contexts where the disparity of power between employees is greater. The feelings of shame, stigma and humiliation that sexual harassment causes in women tends to prevent them from reporting it. “This is part of the wider cultural and social issue of how we as a society have dealt with this problem,” Ms Harris says.

A robust HR approach would involve rolling out practical and scenario-based training to every new employee. Guidelines should be reinforced through posters, company meetings and the intranet. Senior leaders should set the tone and lead by example. With the strongest kind of support from senior leadership, HR should be able to shape a productive and professional working culture.

This task will be harder, in companies where senior leadership does not prioritise gender equality or take harassment issues seriously. In companies where leaders’ primary focus is the protection of the organisation rather than the welfare of their employees, Ms Suff advises HR should make a persuasive business case for positive action.

Quite apart from moral obligations, letting sexual harassment slide can result in huge reputational costs, it is disruptive to team-work, detrimental to performance and dispiriting for employees.

Whether reported or unreported, sexual harassment can damage women’s careers by diminishing their confidence and enthusiasm. It can also amplify employee churn. According to a recent study in the journal Gender & Society, 80 per cent of young women who have been subjected to unwanted touching in the workplace will leave their jobs within two years, which is 6.5 times higher than average.

Neglecting sexual harassment will be counterproductive. With public opinion turning, at the same time as the UK’s controversial employment tribunal fees have been abolished, there will be an increase in employees who feel rightly emboldened to speak out and take action where necessary.

Companies should support them. Inclusive workplaces are good for society and they are good for business, and never has there been a more fortuitous time to build one. These issues are not going to go away and, with the current narrative in the media, it’s time to address this serious problem.