Any manufacturers who feared an economic meltdown in the immediate aftermath of Britain’s vote to leave the European Union must have taken comfort from recent economic data.

September’s Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) figures saw factory activity grow at its fastest pace in more than two years, as the weakness of post-Brexit sterling helped industry towards its best quarter of growth of 2016.

Mec Com, a mid-sized business which provides services including sheet metal fabrication and electro-mechanical assembly, is among the manufacturing businesses enjoying a surprise post-Brexit upswing.

Richard Bunce, managing director of the Stafford-based company, estimates sales are about 12 per cent up since June’s referendum, mostly driven by new export deals.

“We have secured about £2 million of new business,” says Mr Bunce. “I’m not sure what we all expected the morning after the night before [in June]. So far, I can only report growth across all areas of the business, and we hope and plan for this [to continue].”

Brexit boosting business

Those who argue the forecasts that Brexit would spell economic doom were overstated have seized upon the PMI data, which also showed manufacturers taking on additional staff to cope with higher demand.

It is evidence, they say, that the marked decline in sterling is an overdue devaluation that could help rebalance the British economy away from a reliance on imports and consumption towards production and international trade.

“After an expected few weeks of decision-making stasis, caused by the reaction of the markets to Brexit, the real economy has largely returned to business as usual,” says John Longworth, former boss of the British Chambers of Commerce, who left the role to campaign for Brexit.

“The rebasing of the value of sterling… is a massive opportunity for UK manufacturing and this part of the economy should make hay while the sun shines.”

The hard line coming from the May government is renewing fears that access to vital European customers and skills will be compromised

Mr Longworth argues that previous falls in sterling had not been capitalised on because they were short term in nature.

“This time it will last, so it should have a positive impact domestically through import substitution and through reshoring, which is happening anyway because of quality and lead-time issues, and by boosting exports.

“Most countries are secretly trying to devalue [through] competitive devaluation and the UK has been given a golden, free gift.”

Uncertainty continues

Yet even for factories enjoying something of a mini post-Brexit boom, the mood is one of uncertainty. Fears over access to international workers, Europe’s single market and external investment are among the looming dark clouds.

Recent talk of a “hard Brexit” may have helped some exporting manufacturers in the form of a further slump in the value of the pound, but it was additional cause for concern for the EEF, the manufacturing employers’ organisation.

A recent EEF report warns against rushing through a “clumsy” Brexit plan that could do lasting damage to manufacturers. The EEF says it is “critical” that the Brexit negotiations deliver unrestricted access to the single market. It points out that more than eight in ten manufacturers (84 per cent) export to the EU.

The hard line coming from the May government is renewing fears that access to vital European customers and skills will be compromised.

In the event no trade deal with the EU can be agreed, the EEF says that the fallback option of using World Trade Organization (WTO) rules to govern exports could prove costly.

While the EU would not be able to impose discriminatory or punitive tariffs after a UK exit due to WTO rules, the EEF says new tariffs would still be imposed on around 90 per cent by value of the UK’s goods exports to the EU, which could make UK exports less price competitive.

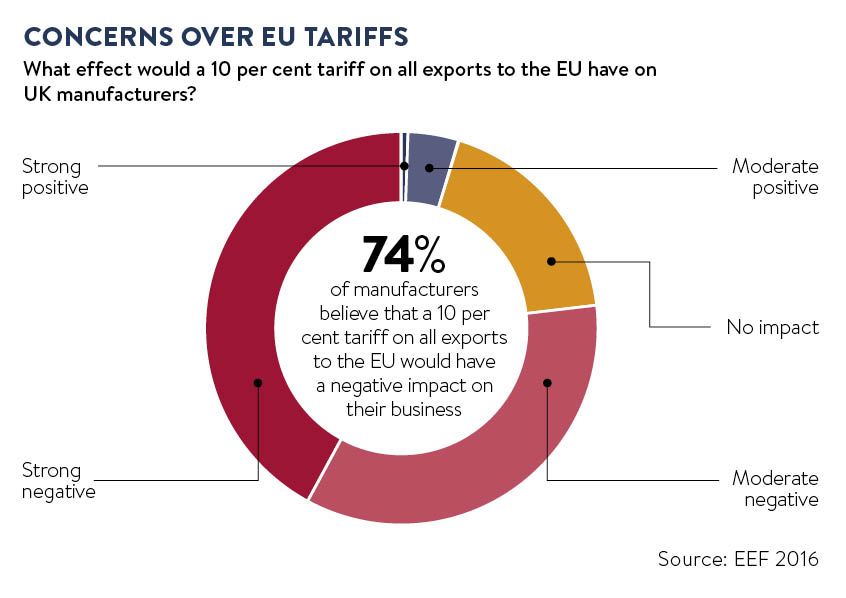

The group warned that three quarters of the 500 companies it surveyed in August said a 10 per cent tariff on exports to the EU would have a negative impact on their business.

Manufacturers react

Anxiety grew when Nissan suggested Brexit had given it pause for thought on whether or not to produce the next model in its all-conquering Qashqai range in Sunderland.

The Wearside Nissan factory is one of the region’s biggest employers and of critical importance to the manufacturing supply chain. The car manufacturer’s decision to stay in Sunderland, announced at the end of October, represents a major corporate endorsement for post-Brexit Britain

With 80 per cent of the cars produced in Sunderland sold overseas, uncertainty over possible trade tariffs was of particular importance to Nissan.

Following a pledge of a package of support from the government, the car maker has decided to stay put, but bosses of smaller manufacturers across the UK are weighing up similar concerns.

Brandauer is a 154-year-old pressing and stamping business. It is one of the largest of its kind in Europe, making precision metal components for international customers involved in the automotive, construction, green technologies and medical sectors.

It might appear to be a prime candidate to benefit from the collapse in sterling, but things are not quite that straightforward for the Birmingham-based business.

“We have requoted all recent euro and dollar opportunities, and these [lower] prices have started to raise eyebrows, but [we have had] no firm decisions in our favour as of yet,” says Rowan Crozier, chief executive.

Instead, despite being a proud exporter sending 70 per cent of its produce abroad, the company is in fact concerned about any further decline in the weakened pound. “There is genuine concern around the long-term increase of raw material costs and there are already the first murmurings of threats from eurozone suppliers of future price increases,” he says.

There are also fears about the ability to hire skilled staff from Europe. “The single market and movement of skilled labour are absolutely vital for UK business. Will they be delivered to the satisfaction of all interested parties? No, I can’t see it I’m afraid,” says Mr Crozier.

“We employ… people from countries such as France, Estonia and Romania. Of course, we try and employ locally where we can, but sometimes there just isn’t the skill base available, and these guys and girls come over and bring real passion, commitment and skill to our business.

“When I talk to them they are feeling a little concerned, driven by the lack of certainty around a government plan. I can’t help but feel the plan is too vague currently.”