On the island of Yap in the West Pacific, giant stone coins called rai have long been used to exchange value. Moving them is often impractical, so ownership is proven by repeating the oral history of a stone’s ownership.

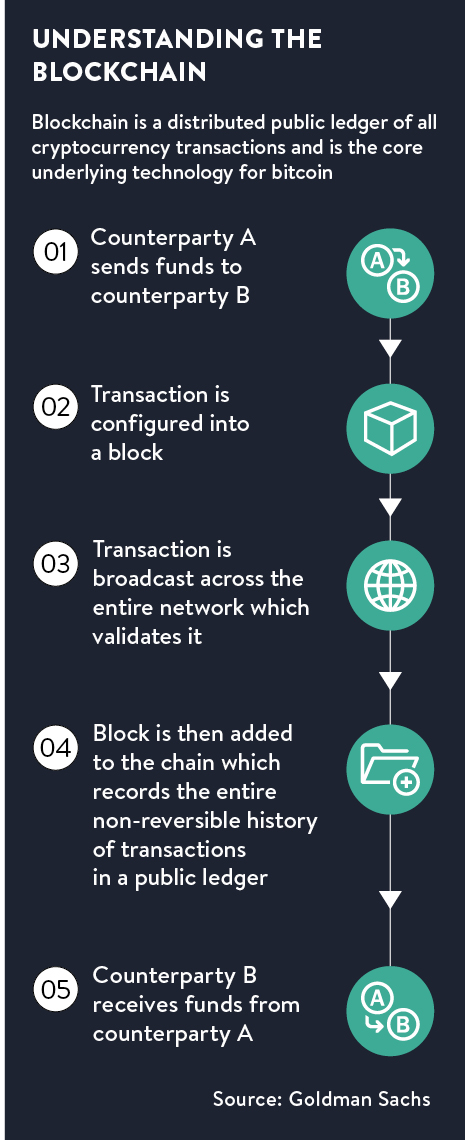

Bitcoins are transferred in a similar, but more secure, way. The history of every transaction is encoded cryptographically in a permanent record called the blockchain. When one person pays another, this payment history, which is distributed and accessible rather than centralised, is automatically checked to ensure the person has previously received the amount of bitcoins they want to spend.

This clever method of managing transactions is now being employed beyond the use of bitcoin as a digital currency. In many ways, blockchain improves upon the current system for payment infrastructure. It creates certainty of ownership and it creates transparency. At present there are centralised ledgers, but these need to reconcile transaction records with the accounts and records of anyone using an instrument, such as cash or shares.

Maintaining a centralised ledger is expensive and relatively inefficient. Distributed ledgers like blockchain require a relatively simple technological set-up, just a computer network and some software, albeit pretty smart software, but the technology is open source allowing many people to use it for other purposes.

As people can only spend what they have received, counterfeiting is impossible and there can be no dispute over who has how many bitcoins. A distributed ledger of transactions can conceivably be used for any unit of value, from loyalty points to cash, to complex contracts. Many technology startups are building their own blockchain-inspired distributed ledgers to take advantage of this.

Public and private blockchain lodgers

They can be divided into two types: private, which connect people who have specifically been given permission to join; and public, like bitcoin, which can be accessed by anyone downloading some software. Each has certain qualities.

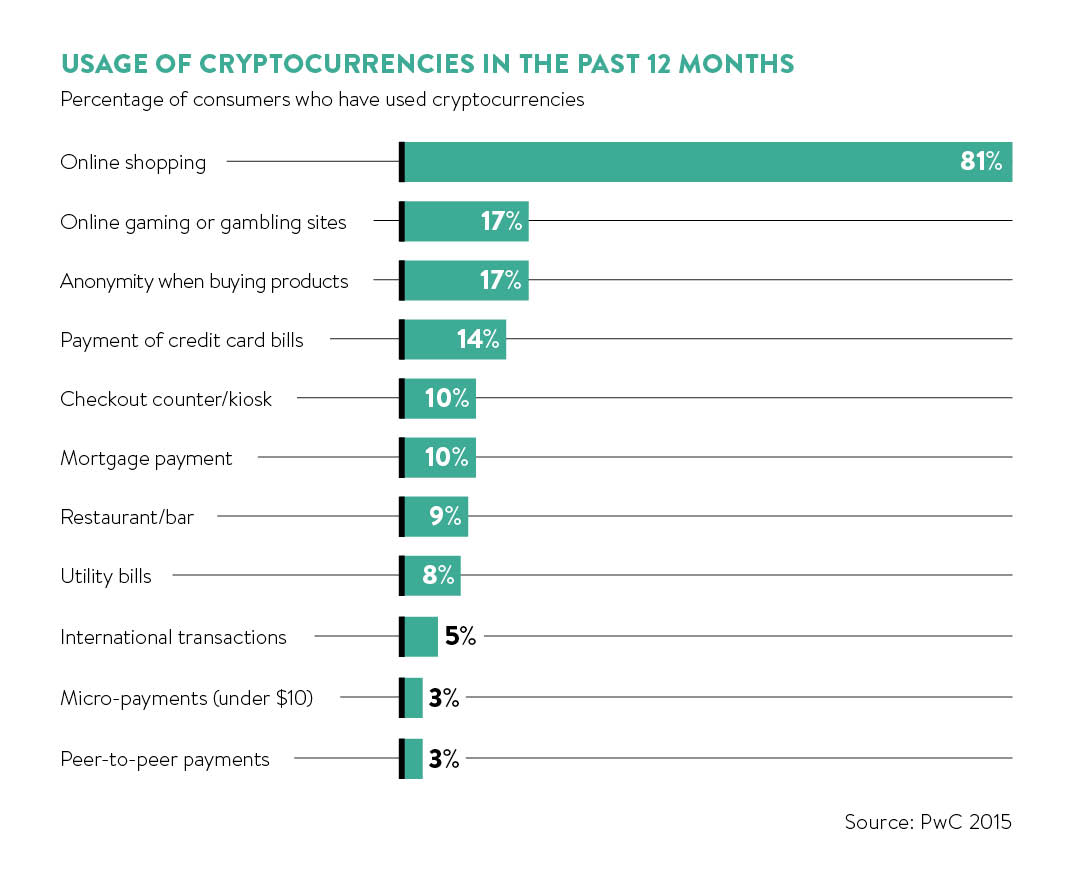

The public blockchain of bitcoin is being used as a transfer system for real currency. BitPay allows a shop to receive payments via bitcoin as a transfer mechanism and receive funds directly to its bank account in the local currency, with lower fees than card schemes. Payment app Circle, which has just launched in the UK, allows consumers to make payments with a bank card that are transferred into bitcoin. Consequently, the use of the public blockchain by consumers and merchants could allow them to make payments from and to bank accounts without using card payment systems.

The ease with which blockchains can be established makes them of interest to firms operating in parts of the world that lack the infrastructure to transfer large-value contracts or amounts of money

“We are really using it as a settlement network, not as a primary currency for consumers, and so consumers never see bitcoin. It’s the token that we use because it can be transmitted and transacted and settled in a final and secure way,” says Jeremy Allaire, chairman and chief executive of Circle. “There is enough liquidity on that platform to enable the crossing of currencies through it and so it becomes a very efficient global media.”

Bitcoin is not a regulated currency and so transactions in it are not regulated directly by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). However, Mr Allaire says that an e-money issuer licence, which Circle has acquired, covers payment activity, currency exchange and cross-border payments for pounds sterling and euros.

For firms who feel uncomfortable about using bitcoin, creating private distributed ledgers that transfer other units of value is an option. Some, such as Ribbit.me, are seeking to use a distributed ledger for non-cash items like loyalty points, allowing them to become interchangeable and potentially driving up their value for multiple scheme users. Others are transferring property contracts or financial derivatives with the potential to trigger automatically contract conditions, such as a pay-out when interest rates move.

The ease with which blockchains can be established makes them of interest to firms operating in parts of the world that lack the infrastructure to transfer large-value contracts or amounts of money.

“A big area of interest has been the supply chain,” says Hywel Ball, assurance managing partner at consultancy EY. “Gas companies especially can look at supply chains in remote locations and be assured that money is going where it should. A lot of focus has gone into financial services because that’s where the big savings can be made, but private blockchains might get adopted in other areas first.”

Time to replace the RTGS?

Perhaps the most fundamental unit being migrated on to a blockchain is real money, specifically that paid and received by the central bank. Setl, the firm that is proposing this shift, believes it is time to replace the real-time gross settlement (RTGS) systems, which were developed in the 1990s to make big transfers between banks, with something more efficient.

In the UK, the RTGS system uses central bank money to settle payments made through the CHAPS high-value payment system and the funds transfer mechanism which supports the CREST securities settlement system.

By settling through the central bank, big banks can have confidence that the transfer of value has taken place. However, this currently requires the big banks to hold large capital buffers at the central banks. By using a distributed ledger to conduct transfers, central bank money could be used to settle transactions 24/7, says Setl’s chief operating officer Peter Randall, and removes the need for bank money to be tied up in a buffer account as the system would provide validation that the transaction can take place.

Challenges

There are several hurdles to overcome before blockchain is more widely adopted. Processing blockchain payments is not fast enough to support large-scale operations. As chains grow they become unwieldy. This is one driver towards the development of private ledgers tailored to overcome this lag. Different ledgers would not interact, but groups such as the R3 collective, which has 41 banks as members, are seeking to overcome the challenge by developing technology standards.

The use of automated value transfer and a permanent transaction record do not eliminate all the problems that can occur in a transaction. If an account is hacked, a theft could be made to look like a legitimate transfer. Market abuse could still be conducted using legitimate transactions at any point and would need to be tracked around the clock, not just in office hours. Consequently, regulators will require some changes to the way finance is run and regulated.

“If you are running transactions on a blockchain, which operates 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, you have then got to have real-time regulation,” says Mr Randall.

This raises further questions about the accessibility of a distributed ledger to authorities, notes EY’s Mr Ball, and also the role of auditors in overseeing transactions on a distributed ledger network.

“A lot of the blockchains will be private networks, so would that blockchain be audited as a chain or would each of the individuals somehow have to form their own view?” asks Mr Ball. “There are several issues impacting the speed of adoption, not least of which is the computing firepower that will be needed to run significant blockchains, but the questions [around regulation] are also likely to slow down adoption.”

REGULATING BLOCKCHAIN

Authorities are keen to allow innovation to develop, but not on any terms. The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has developed a “sandbox” to allow new ideas to be tested in a regulatory environment before going live.

In March 2015, the UK government issued a policy paper entitled Banking for the 21st Century: driving competition and choice in which it pledged £10 million towards research into digital currencies while requiring digital currency exchanges to be subject to anti-money laundering regulations. This levels the playing field with existing financial services providers.

“The UK government, in particular HM Treasury, has been very focused on attracting innovative companies in this space,” says Jeremy Allaire, chairman and chief executive of Circle, a payment app. “That had an influence on us being part of the FCA’s Innovation Hub, a sponsored programme to bring companies through licensing. I think the fact that we are using this cutting-edge technology as part of what we do made it attractive for them to regulate us.”

If regulators are able to use the blockchain to support supervision of financial services, they could become more effective, argues Setl’s chief operating officer Peter Randall.

“It is possible on a blockchain to report every single time a bank fails to make a payment that it should have paid or fails to transfer assets that it had said it would transfer,” he says. “With those things recorded indelibly on a blockchain, a regulator has the capacity to ask banks to reduce rates of failed trades. A regulator can see a bank starting to get into trouble then make the necessary policy adjustments in order to stop that bank from trading, or could inject some emergency liquidity.”

Public and private blockchain lodgers