When Jonathan Pine of BBC’s hit series The Night Manager used his phone to blow up evil warlord Roper’s convoy of armaments, he was only able to do so because of the latest innovations in mobile payments.

Iris recognition, the banking security procedure that Roper mistakenly thought Pine was implementing, is a measure designed to encourage us to increase our use of mobile phones to make payments. But, warlords aside, is it really security that stops us?

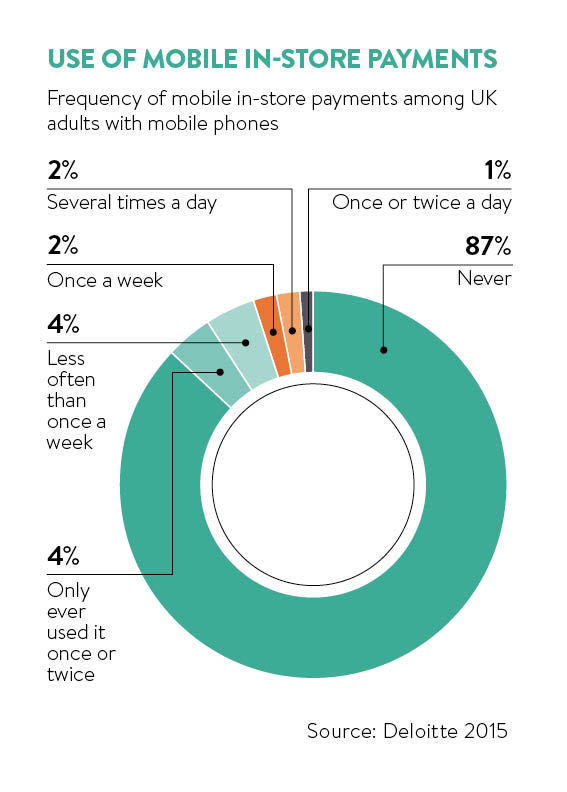

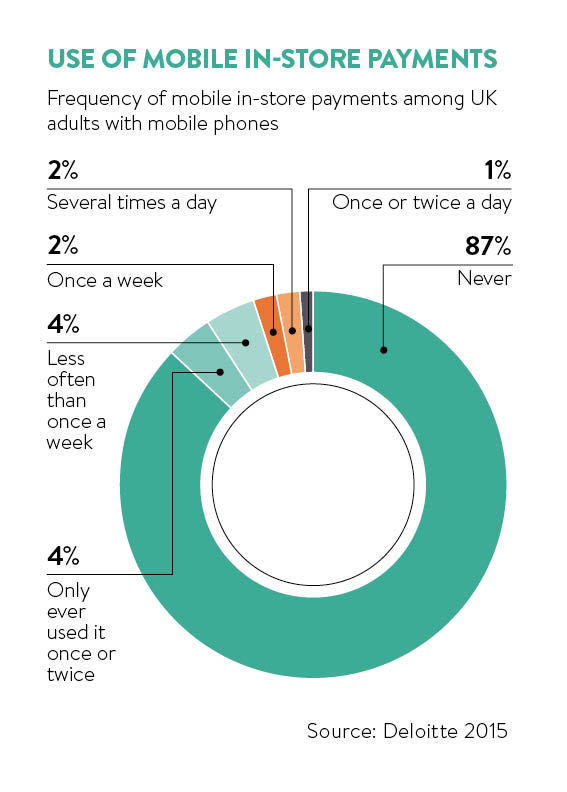

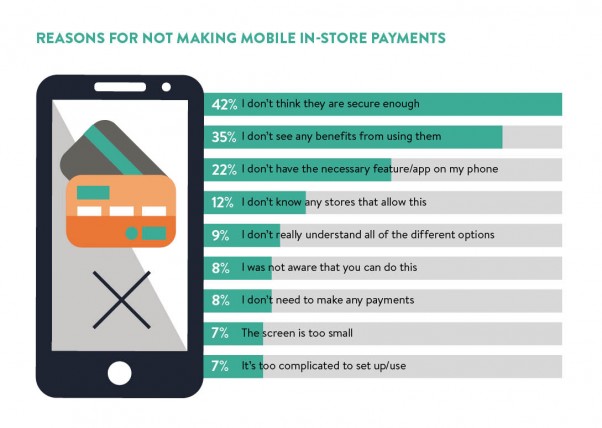

Yes, up to a point. According to Deloitte’s Mobile Consumer 2015 report, 42 per cent cited security as the main reason for not making in-store payments with a mobile, but running it a close second, at 35 per cent, was the fact that we could not see any benefit.

“The customer’s impression is that it’s not secure, although that is not reality. But for consumers there are two things that really matter – saving time and saving money,” says Kebbie Sebastien, managing director of Penser Consulting, a specialist payments consulting firm. “The benefits of mobile payments are still not clear for consumers in developed countries.”

Contrast that, he says, with the phenomenal growth of M-Pesa, Vodafone’s mobile phone-based money transfer service, which operates in Africa, India and Eastern Europe. The service processed 3.4 billion transactions in the year to March 2015.

“The traditional way of sending money home was to hand a wad of cash to a bus driver, with all the problems that implies. So the case was strong for person-to-person mobile payments,” says Mr Sebastien. “But in developed countries, the current system isn’t broken, so to change behaviour requires added incentives.”

Mobile payments disjointed and limited?

The problem for proponents of mobile payments in developed countries is that not only are many of us still quite happy with our cash and plastic, we are also hopelessly muddled about differing systems of payment. We are learning fast to use contactless. In the UK, the use of contactless on the transport system in London, for example, has habituated us to the idea. Also increasing the contactless card payment limit from £20 to £30 has meant an average monthly growth rate in contactless transactions above £20 of 19.1 per cent between October 2015 and March 2016, according to Visa Europe. But even so, contactless is far from ubiquitous.

“People often don’t realise they have a contactless card. I have seen a customer hand over a card in a busy restaurant, and be surprised when the waiter hands it back and says the payment is made,” says Lawrence Freeborn, senior researcher and banking technology analyst at IDC, a market research and analysis firm. “And mobile? That’s a pain to use – people don’t like fiddling with their phone at the front of the supermarket queue.”

Customers still don’t regard mobile payments as a more convenient way to spend – the onus is on companies to provide a seamless customer experience

For consumers, mobile payments methods can seem disjointed and limited; the lack of a central nervous system for payment providers has meant each provider must negotiate separately with retailers and merchants. So, for example, you can download MasterCard’s Qkr! app, which allows you to pay easily using your mobile, but at only three UK restaurant chains, with two more to be added in the coming year, it’s hardly a comprehensive service for a night out.

To pay with a mobile, you might need to download an app from a bank for some services, from a phone provider for others or from the restaurant itself, for example. Why bother to try and remember at which coffee shops you can pay with your mobile, when you can just put your hand in your pocket and pull out a tenner that is accepted everywhere?

Retailers favour cashless societies

Yet the push towards a cashless society is very strong from the supply side since it enables retailers to capture information about their customers, and governments to reduce problems such as money-laundering and tax-dodging. The launch of Apple Pay 18 months ago changed the landscape too.

“Forty per cent of iPhone 6 owners used Apple Pay at least once within the first nine months after launch,” says Sameet Gupte, executive vice president and global head of banking and finance at Virtusa, an IT consultancy. “There is clearly plenty of interest in mobile payments. But the lack of consistent, widespread engagement is a clear signal that customers still don’t regard mobile payments as a more convenient way to spend – the onus is on companies to provide a seamless customer experience.”

“Forty per cent of iPhone 6 owners used Apple Pay at least once within the first nine months after launch,” says Sameet Gupte, executive vice president and global head of banking and finance at Virtusa, an IT consultancy. “There is clearly plenty of interest in mobile payments. But the lack of consistent, widespread engagement is a clear signal that customers still don’t regard mobile payments as a more convenient way to spend – the onus is on companies to provide a seamless customer experience.”

So what can payment providers do to persuade us to use our phones? “It’s all about context,” says Jeremy Allaire, chairman and chief executive of Circle, a tech company that is aiming to change how we use money. “The interaction isn’t just about payment – it’s about support issues, it’s about communication with the customer.”

Earlier this month, Circle teamed up with Barclays to offer e-money for cross-border payments using blockchain, a ledger or database of cryptocurrency transactions. Circle believes it is not simply cash that is outdated – it’s money itself. “This is not about mobile, it is about money becoming digital,” says Mr Allaire. “Money is giving way to something defined by software – the future of money is messaging.”

Loyalty programmes

Just as we no longer have the gold standard backing our currencies, so we will no longer have physical notes and coins. But that may be a step too futuristic for many at the moment. Key to increasing mobile payments, say consultants, is the far simpler concept of a loyalty programme. So, paying for a meal with an app allows the restaurant to track and monitor its clientele, but then to encourage them back with special offers and discounts.

Technology such as blockchain is also allowing merchants to offer own-branded loyalty programmes. For example, at the end of last year, mobile payments processing network Boloro chose to offer their merchant customers a loyalty programme using blockchain technology from tech startup Ribbit.me.

According to Ann Camarillo, Boloro president and chief executive: “We wanted a way to further differentiate ourselves as we enter new markets, while at the same time help merchants in our network improve their revenues and customer loyalty.”

Ribbit.me believes that the flexibility of blockchain, which makes it possible to exchange virtual currencies over the net, making cross-border payments quicker and easier, will allow loyalty programmes to swap and exchange in a similar fashion. RibbitRewards are tradeable loyalty “tokens”, so customers can redeem their loyalty points from one sector to another, paying for a meal with air miles, for example.

Of course, success depends on merchants being willing and able to accept Boloro payments and, just as 50 years ago not all outlets would accept plastic or would pick and choose which plastic to accept, so not all merchants will accept mobile payments or will choose between competing processors.

“We have a huge problem with legacy point-of-sale [POS] systems,” says Lisa Falzone, chief executive of Revel, which offers a POS system based on iPads. “POS is a three to five-year investment, so it is not going to change overnight.”

The technology that allows us to pay for goods and services with a contactless tap of a card, and with mobile phones, has been around for decades; it was 1999 when Nokia and Visa piloted a mobile phone that could pay over the net. But will 2016 finally be the year when we reach the tipping point that makes cash redundant?

“Mobile payment has been about 15 months away for about 15 years,” says Mr Sebastien. “But it has changed as smartphone penetration has increased [it is now at 76 per cent in the UK, according to Deloitte] and is rapidly gaining momentum.”

Certainly the trajectory is only one way. The volume of non-cash payments at 52 per cent exceeded those made by cash for the first time in 2014, with cash accounting for just 17 per cent of the total value of consumer payments, according to Payments UK, the trade association for the payments industry. Just don’t write off cash quite yet – even if you’re an arms dealer.

Mobile payments disjointed and limited?

Retailers favour cashless societies