Typically reported views on the future of lifestyle retailing come down to some ultimate battle between bricks and mortar and online stores, the former offering the experience, the later the convenience. But might, potentially, tomorrow’s shopping paradigm be more at the blurred boundary between the two – bricks and clicks?

John Miln, chief executive of the UK Fashion and Textile Association, posits a future of stores of limited shop-floor stock, available to see should the customer want it, but otherwise selling a greater range digitally, with the option to take away the item when purchased or, as online, have it delivered. “The question,” notes Richard Perks, director of retail research at Mintel, “is whether that approach can work out economically; real shops and staff being expensive.”

But a physical shop is perhaps necessary for many big retail names. Online shopping is, after all, still not for everyone. However, digital shopping will become more ubiquitous. In South Korea, for example, Tesco has experimented with virtual store displays in subway stations, via which shoppers can use a smartphone to scan QR codes and have the goods delivered the same day. But this can also come with choice paralysis and the hassle of returns.

Online retail sales in the UK last year amounted to just 11.3 per cent of the total. Meanwhile, increased urbanisation – house prices forcing younger generations to rent, but giving them the opportunity to live in a city centre, which in turn means lower rates of car ownership – is driving a demand for small, convenient, local stores and a return to traditional mercantile values.

Ask yourself if there is any point in shops now and clearly there is, which is why online retailers are opening physical spaces

“There’s a new place for independent stores, for old-fashioned personal service, an edited choice of products and so on,” says Mr Miln. The same might also be said to apply to the streamlining of online stores to make shopping as uncluttered, fast and as efficient as possible. Skullcandy, Boucheron and Tag Heuer, for instance, have all trialled desktop camera-based software that allows shoppers to “try on” their products digitally at home.

“Ultimately, the question is really one of whether new generations of shoppers have the same desire to touch and feel products before they buy, as older people tend to want to do,” Mr Miln adds.

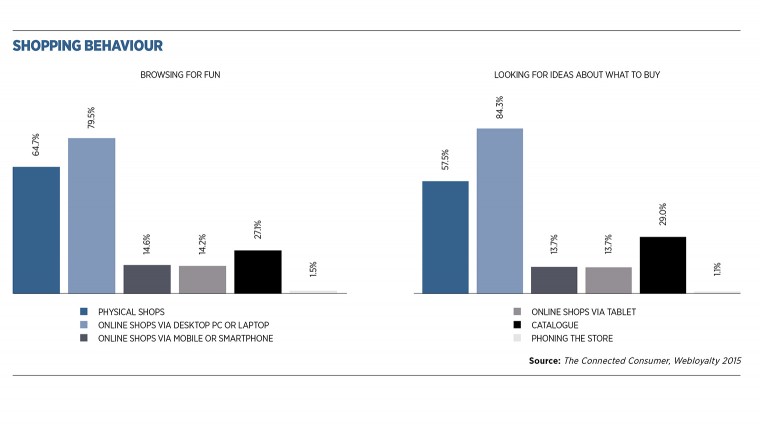

Certainly, despite the overheads, retailers in general might well favour real stores, in part because when people shop online they buy less, so incentivising them to get back into stores is important. “There’s no serendipity online and actually online is difficult to browse,” says Mr Perks. “And clearly people still want to go to shops, although the high street of the future may not be a place to buy, but more a leisure outlet.”

So-called “third space” and experiential retail has, in recent years, seen the diverse likes of Dixons launch studio workshops in its stores or Moss Bros create library areas in which shoppers can learn about the latest trends. Levi’s has run print and photography workshops. Upmarket brands, such as Dunhill, Louis Vuitton and Austin Reed, host deluxe in-store events and have restyled themselves more as shop-meets-private club. Other brands have collaborated, placing a pop-up Square Mile Coffee Roaster inside a branch of cosmetics company Aesop, for example, to reinvent shops more as a hybridised community hubs. The more time you spend with a retailer, the thinking goes, the more likely loyalty will grow.

“Ask yourself if there is any point in shops now and clearly there is, which is why online retailers are opening physical spaces,” says William Higham, founder of futurist agency Next Big Thing. “But that is in order to do what you can’t do online – to interact. We’re seeing a merger of retail, hospitality, entertainment and education, with an element of ‘gamification’ too.”

He cites, for example, sports brand Asics’ use of in-store video walls, from which customers can also shop, or Jimmy Choo’s use of GPS-based social networking services such as Fourspace to run treasure hunts for its shoes. Then there are certainly more gimmicky ideas, albeit ones that point to the experimental nature of much retail now, including in-store 3D body scanning to help select the best fitting clothes, for example. Musical fitting rooms from StarHub in Singapore personalise the in-store experience by giving each garment a radio frequency identification tag, prompting the changing room to play a style of music matched to the style of clothes – and then allows you to buy the music too.

Indeed, such developments could prove just the tip of the iceberg for how radically retailing, online and off may be transformed in years to come. Frightening thoughts in many ways. Mr Higham suggests we might well expect what has been dubbed f-commerce, after Facebook or Friends, in which shoppers themselves get a commission on sales of products they recommend to their peers and, as is already happening via Instagram, the advent of “everywhere retail”.

“That’s when everything will be shoppable – on the TV, in shop windows at night, in magazines,” says Mr Higham. “You could see a product anywhere and be able to buy it there and then because, since we’re increasingly bombarded with information, if you don’t buy there and then, invariably you don’t.”

One thing does seem certain: tech, notably the internet and the smartphone, has already changed the way retail operates and will continue to do so, even if it is not working in opposition to traditional stores as is sometimes suggested.

“Whether a store sells online or off is, ultimately, completely irrelevant,” stresses Mr Perks. “You might visit a store occasionally, for reasons other than to buy, but in the end you buy as best suits you, online or off. To set them against each other is a red herring. In fact, it’s more about bringing them together.”