“Flawless skin is the most universally desired human feature.” So said lauded zoologist Desmond Morris in the 1960s. Half a century on and academics, such as evolutionary psychologist Bernhard Fink, are still convinced of its cross-cultural appeal.

“Skin condition profoundly affects the way we judge people’s age, health and attractiveness,” he says from his Göttingen office. His studies show it affects your “mate value”, essentially being an outward symbol of your physical health and fertility.

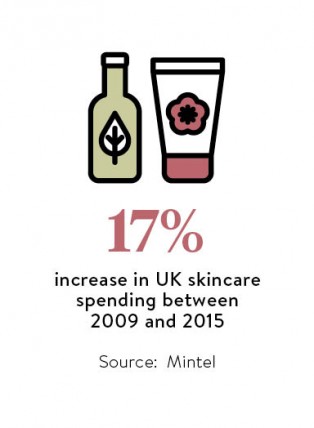

Which is probably why, according to Mintel, we spent £1.07 billion on skincare in the UK last year, up 17 per cent since 2009. A-list cosmetic doctor Vicky Dondos, co-founder of London-based Medicetics, thinks this is in large part down to skincare’s ability to tap into the huge wellness trend.

It’s all about the “glow”

Her stylish clients are now looking for skin that is fresh and radiates health. For them it’s less about removing wrinkles and more about getting the “glow”. And glow comes from skin that is unmarked, clear of blemishes, redness and pigmentation, all of which increase with age.

Though Dr Dondos is well known for her work with Botox and fillers, she works on the complexion with lasers, peels and products. “They can take so many years away, with absolutely no risk of changing your look or expression,” she says. “The end-point is to have a patient tell me they no longer need to use their concealer.”

In Korea, China and Japan there is a similar desire for a flawless complexion, but with the additional request for pale skin. Pale is aspirational because according to US beauty magazine Allure: “In China darker skin is still associated with peasants.” The magazine reported women wearing “facekinis”, lightweight balaclavas, to ensure zero sun damage.

As human beings we are hard-wired to observe that the more uneven your skin, the less attractive, less healthy and older you are perceived to be

At the other end of the spectrum is the West’s love of a suntan. Despite repeated warnings about UV rays causing skin cancer and accelerated ageing, a 2014 survey reported by The American Academy of Dermatology said 59 per cent of US college students have tanned indoors. A survey, reported in The Guardian, showed 50 per cent of people here admitted returning with a tan was the single most important reason for going on holiday.

There are many reasons why Western women want a tan, but its beginnings are widely attributed to Coco Chanel. Her bronzed limbs signaling an aspirational life spent on beaches, yachts and horseback, when most people were stuck working in gloomy factories. Now the prominence of naturally honey-skinned celebrities, like Kim Kardashian West and Jessica Alba, is thought to be stoking the appeal.

Interestingly, Dr Fink believes Western women’s desire for darker skin and Eastern women for paler, both have the same end-game. “They are actually doing the same thing,” he says, “trying to remove discolouration”, as a tan hides blotches and blemishes in the short term.

“It’s about homogeneity of skin,” says Dr Fink. “As human beings we are hard-wired to observe that the more uneven your skin, the less attractive, less healthy and older you are perceived to be.”

Skin bleaching

Can this explain the worrying trend for the practice of illegal skin bleaching in places like Africa and Jamaica? Partly yes, because uneven skin tone is a primary concern for many women with black skin and these creams purport to create uniformity.

But there’s another reason too, says Ateh Jewel, a beauty journalist and creator of Jewel Tones Beauty, a website dedicated to showcasing beauty products and techniques for women with deeper skin tones.

“Culturally, we’ve been told lighter or whiter is better or higher status,” she says. Evidence of this was Kenyan-Mexican actress and film director Lupita Nyong’o telling Essence’s Black Women in Hollywood event that, as a child, she prayed to God she would wake up lighter skinned. “Skin bleaching is happening here in the UK too,” adds Ms Jewel, “but is under the counter.”

Dr Bav Shergill, consultant dermatologist at the British Skin Foundation, is concerned about its dangers and says products can contain dangerous levels of mercury, steroids or hydroquinone. Side effects can include increased pigmentation, foetal abnormalities and psychological damage.

Ms Jewel recalls a story about the death of a Nigerian relative at 63, whose kidney failure, the family was told, was due to accumulated toxins from 30 years of skin bleaching with illegal creams. It’s all about as far away from skin health as you can get. But there is some good news with evidence of greater diversity in the media’s vision of beautiful skin.

As the world becomes more and more diverse – the United States census shows the US mixed-race population has grown by 32 per cent since 2000 – so there will be more and more different skin tones. Fingers crossed this inspires a proliferation of products and treatments that, to use a beauty buzzword, will help “optimise” all of them.

That way everyone, from China to Kenya via England and America, can finally feel truly comfortable in their own skin.