In the last decade, non-surgical cosmetic treatments in the UK have developed and expanded beyond recognition.

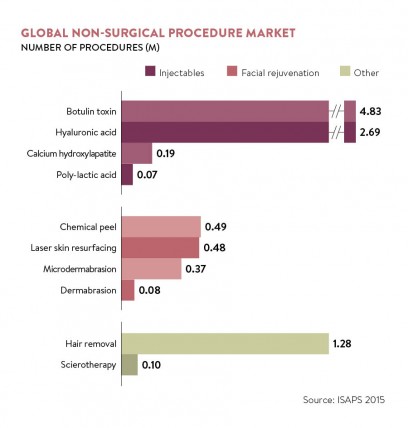

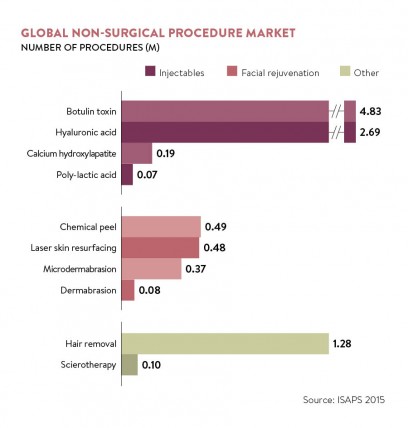

The beauty-conscious customer can now plump for anti-wrinkle injectables, dermal fillers, laser hair removal, skin rejuvenation techniques, such as microneedling, and intense pulsed light for skin-lightening.

The demand is so high that unethical practitioners see the industry as a quick way to make money

Almost every high street has salons and surgeries offering a range of procedures. It’s not surprising that, according to industry analysts Mintel, cosmetic interventions in the UK are worth more than £3.6 billion, with nine out of ten procedures non-surgical treatments.

But with this surge, rogue practitioners are attempting to muscle in with potentially dangerous consequences, as injections performed poorly carry the risk of infection, nerve and tissue damage or allergic reactions.

Natali Kelly, an aesthetic nurse practitioner at Omniya MediClinic, in London’s Knightsbridge, says: “The demand is so high that unethical practitioners see the industry as a quick way to make money. In my clinic I see and correct a lot of bad work.

“Often the public are naive or go for a cheaper price over quality. It upsets me that often they have no idea about risks and side effects, and what has been injected into their face.”

After concerns about the standards and promotion of some of the cosmetic work taking place, the government asked NHS England medical director Professor Sir Bruce Keogh to carry out a review in 2013.

Even he was shocked by the lack of regulation and wrote: “A person having a non-surgical cosmetic intervention has no more protection and redress than someone buying a ballpoint pen or a toothbrush.”

There have since been moves to improve regulation in this area. Recently the General Medical Council (GMC) published its first guidance on the subject, with new rules due to be introduced from June for cosmetic treatments.

They rule out supermarket-style two-for-one offers and pressuring patients to buy treatments. Instead doctors must discuss the proposed procedure with the patient, who must be given time to reflect before agreeing to proceed.

The GMC is clear about the need to help drive up standards and ensure all patients, especially those who are most vulnerable, are given the treatment, care and support they need.

GMC’s guidelines

The guidance has been well received. James Bird, medical director at private dermatology clinic Ethos Medical, says: “We wholeheartedly welcome the GMC’s guidelines. The industry has grown hugely over the past ten years and treatments, which were once considered the preserve of the rich and famous, have now become, for many, part of a regular grooming regime, akin to visiting the hairdresser.

“Sadly, this expansion has also seen a worrying increase in substandard procedures being performed by underqualified personnel, in unsanitary surroundings, using inferior products.”

Bruce Richard, a consultant plastic surgeon who works in the NHS and privately through Medstars.co.uk, says that for those who are already regulated and properly trained, the guidance should have little impact on their business beyond increased customer demand. But the guidance will ultimately help to improve trust and confidence within the industry, he says.

However, some say that while helpful, the guidelines cannot possibly address all the issues in this very complex area.

Patient undergoing intense pulsed light treatment

For a start, the guidance applies only to doctors, when many other health professionals, such as nurses and dentists, and even non-health qualified practitioners such as beauticians, are allowed to perform many of these techniques.

Mr Richard says the changes could push other professional bodies, such as the dental or nursing councils, to regulate their members undertaking such procedures.

But Dr Mervyn Patterson, a former GP who runs Woodford Medical with five clinics across the country, says until that happens: “It’s not a level playing field. Nurses and dentists do not have to follow the same rules.

“The vast majority of those having injectable treatments have them done by people who are not affected by this guidance, which doesn’t keep people any safer.”

He believes that if doctors have to give patients a cooling-off period for a filler, they will simply choose an alternative clinic which will do it immediately, giving them a competitive advantage.

Others say it is ludicrous that those who present the least risk to patient safety – namely doctors – are being regulated more than laymen who can act with impunity. While only doctors, nurses and dentists can prescribe injectables, anyone can administer them.

A further issue is that clinics in England which offer cosmetic surgery, such as facelifts, have to be licensed by the Care Quality Commission (CQC), the same health body which inspects hospitals. It carries out announced and unannounced checks, and these clinics also often offer non-surgical treatments.

But centres which only offer anti-wrinkle injections, chemical peels, laser and intense pulsed light treatments, such as hair removal or skin rejuvenation, do not have to be licensed by the CQC. According to a CQC spokeswoman, any extension of the body’s remit would be a matter for the government.

Non-surgical cosmetic treatments in Scotland

All eyes are currently on Scotland where private clinics offering non-surgical cosmetic treatment are now regulated by Health Improvement Scotland, the equivalent of the CQC north of the border.

With the absence of state intervention, a number of initiatives have been set up involving voluntary regulation, including clinics joining independent registers which use a quality kite mark.

One is Save Face, which accredits individual doctors, dentists, nurses and clinics. The organisation gathers information on registration, insurance, training and consent procedures from an online questionnaire, then a nurse assessor visits the establishment. It is now in the final stages of becoming accredited by the Professional Standards Authority, which means it will be recognised by the Department of Health and others.

Director Ashton Collins says she is delighted that there are now almost 400 practitioners on the register. “We’re passionate about eradicating unsafe practice from the non-surgical cosmetic industry by raising standards throughout the country,” she says.

So what of the future? Health Education England, the body responsible for standards within the healthcare workforce, has published a report setting out the qualification requirements for practitioners who perform these types of treatments.

One thing is agreed that the industry is only going to get bigger – making the issue of regulation a hot topic.

GMC's guidelines