Every skin-boosting formula will have its limitations, especially if you’re partial to after-work drinks and have maintained a ten-a-day habit for longer than you care to remember. Collagen will collapse, elastin will deteriorate, cells will slow down, and a cream made from unicorn tears and Himalayan snow is unlikely to stall the depressing inevitability of the ageing process.

An anthropological glimpse at how other cultures live – and consequently age – would suggest that the elixir of youth does not exist in cream form, but in our individual lifestyle choices, most notably the food we choose to put in our bodies. The Kitavan Islanders from Papua New Guinea, for example, are well documented for the fact that there isn’t a single pimple among the tribe. It’s also worth noting they also don’t have cases of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, heart failure, dementia or blood pressure problems.

The anomaly was relayed to the rest of the world in the early noughties by Dr Loren Cordain, who proceeded to put the tribe on a Western diet of high-GI (glycaemic index), processed foods. Zits ensued. The trial proved what we all now know to be true that a low-GI, hunter-gatherer or “paleo” diet is optimum for all-round health, never mind the appearance of our skin.

The gut-skin connection is so strong that facial skin is often used as a diagnostic tool by doctors of Chinese medicine and nutritionists. In traditional Chinese medicine, the lips mirror the digestive system; the cheeks, the lungs; the chin refers to the kidneys.

Attempting to improve skin health by relying solely on the outside-in approach is like trying to light a fire with a wet match

Skin reveals deeper imbalances

For a nutritionist, the skin presents clues to deeper imbalances. A vitamin B3 deficiency might show up as hard scaly skin or poor suppleness, a lack of copper. Neither of these diagnostic methods is bullet-proof, but they point to one inescapable fact that attempting to improve skin health by relying solely on the outside-in approach is like trying to light a fire with a wet match.

Nowhere is the effect of diet on skin more apparent than in the case of acne. While hormonal levels, emotional stress, genetics and body mass all play a part in acne, studies confirm that systemic inflammation caused by GI distress is a precursor to spotty skin. Equally, abdominal bloating, which is a tell-tale sign of inflammation, is 37 per cent more likely to come hand in hand with acne, according to research published by the Japanese Dermatological Association.

The most current studies point to the fact that acne can even be treated with fermented foods and probiotics. One popular theory, from research at New York State University, suggests acne is due to an overabundance of bad bacteria in the gut, which causes the lining of the intestine to become permeable, (a condition unfortunately referred to as leaky gut). Toxins slip through the gut wall causing allergies, inflammation and, in those who are susceptible, acne.

“I think that this is very plausible,” says cosmetic dermatologist Sam Bunting. “We know that the typical Western diet with its high-GI index and low-fibre content is associated with lower levels of ‘friendly bacteria’ lactobacillus and bifidobacterium. I don’t think we have any really conclusive studies yet on the benefits of probiotics in acne… but that doesn’t rule out the possibility. I always recommend oral probiotics when I’m prescribing oral antibiotics for acne patients.”

Anti-ageing elixirs

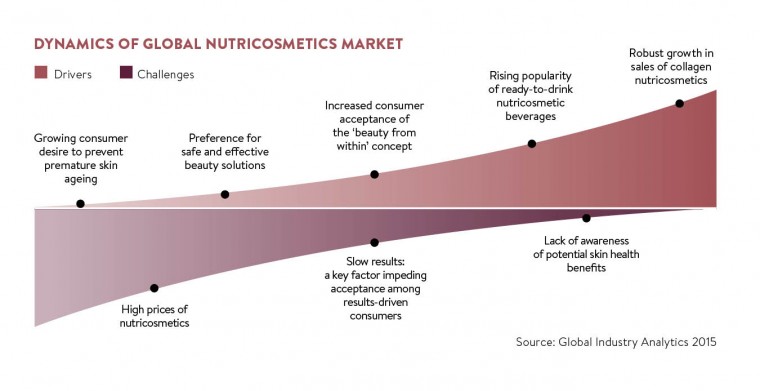

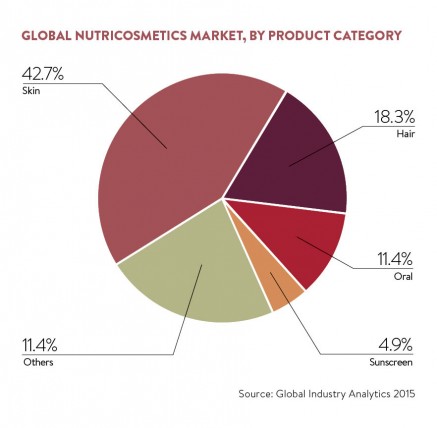

Considerably more glamorous than acne-busting microbes are the anti-ageing elixirs that have flooded the beauty market in recent years. Formally known as nutricosmetics, these pills and potions play on the idea of beauty from within. Anti-ageing drinks, such as Gold Collagen, Fountain and Pure HA, have taken the UK by storm.

The global appetite for ingestible beauty is so great that the wellness supplements market is expected to reach $7.16 billion by 2020, according to Transparency Market Research. Should you venture further afield, you might find anti-ageing marshmallows in Japan or a tan-boosting beverage in Brazil.

The central ingredient in the most popular supplements is collagen. Paired with keratin, collagen makes for stronger, more resilient skin; it is the glue that holds everything together. A close runner-up is hyaluronic acid, the naturally occurring sponge-like substance that plumps skin and cushions everything from your joints to your eyeballs.

Levels of both these ingredients decline with age so it seems perfectly reasonable to assume that scarfing down a supplement every day would top up our levels and thus circumvent the outward signs of ageing. But dermatologists are less convinced.

“I know of no mechanism to ‘import’ dietary collagen and hyaluronic acid molecules intact to the skin,” says Dr Bunting. “They are broken down into their basic building blocks like other dietary proteins and carbohydrates, and are sent where the body needs them most. The skin doesn’t get special treatment.”

In other words, the body will not reliably use the active ingredient to improve your skin over, say, the cartilage in your left knee. Ironically enough, Dr Bunting maintains that skincare or, better still, microneedling would be a more effective route than supplements.

Supplements have inherent limitations in just the same way that skincare has its own set of limitations

The other pitfall with skincare supplements is their bioavailability. In layman’s terms, this is the amount of an active ingredient that the body is able to absorb from a supplement. A product might deliver the right ingredients in the right concentration, but it’s fairly useless if none of it is assimilated into your system.

And then there is the not-so-small matter of a GI tract hell-bent on breaking down everything it encounters. A person with a healthy gut is likely to get 25 to 50 per cent absorption from an oral supplement or vitamin, depending on which study you read. The only way to bypass the GI tract is to mainline vitamins and minerals into your body intravenously, a powerful and costly approach to skin health that is, unsurprisingly, all the rage on the west coast of the United States.

As you might expect, large-scale controlled clinical studies verifying the efficacy of supplements on skin health are thin on the ground. That doesn’t mean pill-popping or mainlining antioxidants isn’t an effective measure. It simply means that we have to go on anecdotal evidence most of the time. Supplements have inherent limitations in just the same way that skincare has its own set of limitations.

Regardless of the debate over their efficacy, the appetite for supplements points to the glaringly obvious fact that the Western diet needs a dramatic overhaul. As Michael Pollan, author of The Omnivore’s Dilemma, pointed out to scientists in a 2009 lecture: “The Masai subsist on cattle blood and meat and milk, and little else. Native Americans subsist on beans and maize. And the Inuit in Greenland subsist on whale blubber and a little bit of lichen. The irony is that the one diet we have invented for ourselves – the Western diet – is the one that makes us sick.”

Supplementing for skin health, therefore, is not really separate from supplementing for overall health. The skin, after all, represents our internal wellbeing and an attempt to plaster over the cracks with a ‘cosmetic’ pill is missing the point entirely. Choosing clean, sustainable foods over healthy-looking food-like substitutes will always be more effective than any pill. As the disclaimers on the pack clearly state, no supplement is intended to replace a balanced, healthy diet.

CASE STUDY: COCONUT OIL

Lithe, bright-skinned yoga students use coconut oil to aid digestion, kill candida or boost immunity against colds. They slather it over stretch marks, put it into funny looking teas, stick it on their cheekbones, use it as a hair conditioner and as a deodorant. It is the organic, non-toxic alternative for just about everything you would buy in a chemist or supermarket.

So it was only a matter of time before the masses would cotton on to the versatility of coconut oil, drawn in by its many culinary applications. Coconut oil, it turns out, is an ideal replacement for plant-based oils when cooking since it is thermally stable and free from cholesterol.

But its reputation as a cure-all moisturiser may be overhyped. On normal skin types, the medium chain fatty acids absorb into the skin quickly and give it luminosity. But dermatologists, including Dr Sam Bunting, would prefer it was kept in the kitchen. “It is one of the most comodegenic oils around,” she protests. Comodegenic substances block pores, causing or exacerbating breakouts. “I see patients who are a sea of bumps from using it as a moisturiser.”

Skin reveals deeper imbalances