Our planet might be blue, but we may still be left thirsty. While almost three quarters of the Earth’s surface is covered in water, less than 3 per cent of that resource is actually freshwater, of which maybe only 1 per cent is readily accessible. We depend on that 1 per cent.

Not surprisingly, the critical hundredth is in high demand. Research published in the journal Science Advances found that as many as four billion people worldwide, more than half the global population, suffer water scarcity at least one month a year.

For many, sadly, things might only get worse, before they get better. Mark Fletcher, global water leader at Arup, says: “Growing water scarcity is an overarching global problem. At least two thirds of the world’s population will face ‘water stress’ by 2025 and the number of people affected by floods could increase by a factor of three by 2100.”

In its ranking of the top five global risks of greatest concern over the next ten years, the World Economic Forum rated water crises number one, marginally higher than failure of climate change mitigation and adaptation, and significantly ahead of extreme weather and food crises. All four risks are interrelated.

Water scarcity accelerating

Water scarcity accelerating

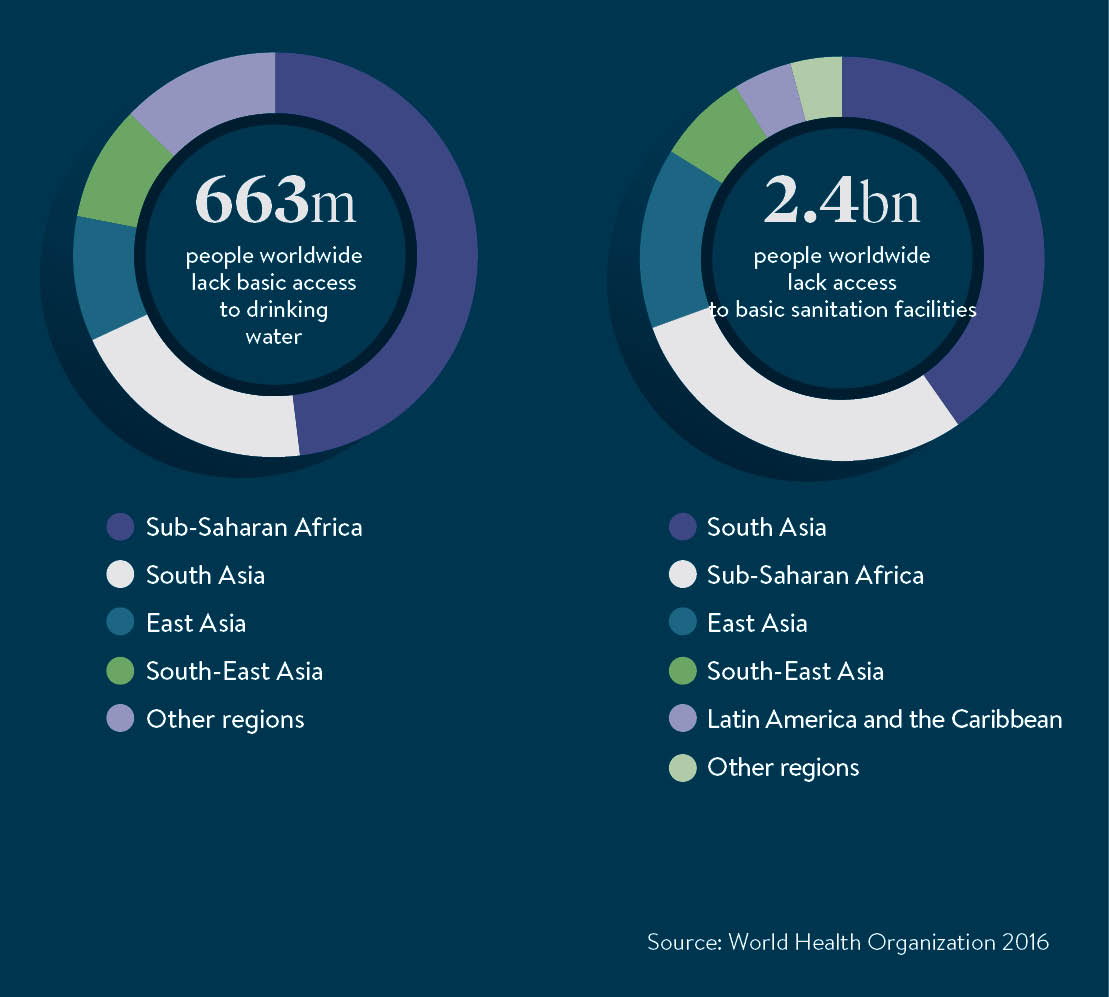

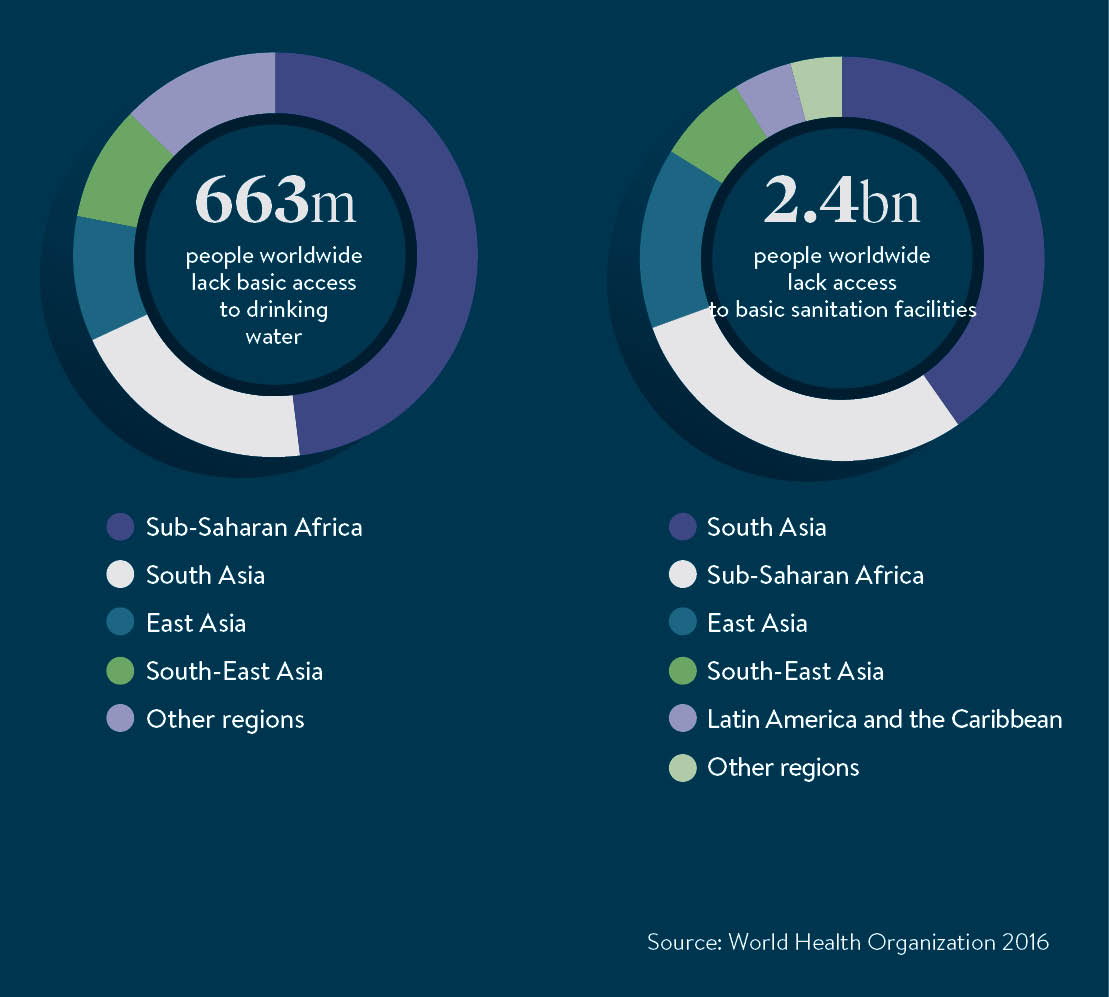

The effects of water scarcity are particularly severely felt in Africa, where the cost is being counted across entire economic regions. Dr Richard Munang, co-ordinator of the Africa Regional Climate Change Programme of the United Nations Environment Programme, says: “The World Bank estimates that water scarcity exacerbated by climate change could cost some regions in Africa up to 6 per cent of GDP by 2050 due to impacts on agriculture, health, and incomes. This is in addition to the very low baseline, where sub-Saharan Africa will require investments of some 2.7 per cent of GDP, or $7 billion annually, to reach goals of water and sanitation.”

Alongside climate-related effects, there are two other major global megatrends accelerating impact of water scarcity worldwide – population growth and urbanisation.

More than half the world’s rising population already lives in cities and that proportion is forecast to grow towards 66 per cent by 2050. This will mean more than two billion extra inhabitants needing water for drinking, washing and food preparation. The UN predicts close to 90 per cent of this increase will be concentrated in Asia and Africa.

Water stress as a result of urbanisation cuts across all climate maps and geographies. For instance, cities in Brazil, a country famous for rainforests and home to one eighth of the world’s freshwater, are surprisingly experiencing drought conditions similar to those faced in Iran, known for its deserts.

São Paulo, located in the south east of Brazil and the largest megacity of the southern hemisphere, has been wrestling with the effects of the worst drought for generations. Equally, Tehran, capital of Iran, and now home to over one tenth of its population, is once again warning citizens about water rationing.

Time for change

There is good news, however. Despite desperate situations and dire forecasts, there are abundant opportunities for change.

Dr Munang, for one, is adamant both policies and proven technologies exist to mitigate against even the worst of water crises projections. With application of these known solutions, he insists the outlook remains highly optimistic for Africa. “Improved water stewardship pays high economic dividends,” he says. “When governments respond to shortages by boosting efficiency and allocating even 25 per cent of water to more highly valued uses, such as more efficient agricultural practices, losses decline dramatically and for some regions may even vanish.”

The value of water is now an emerging metric on the balance sheet

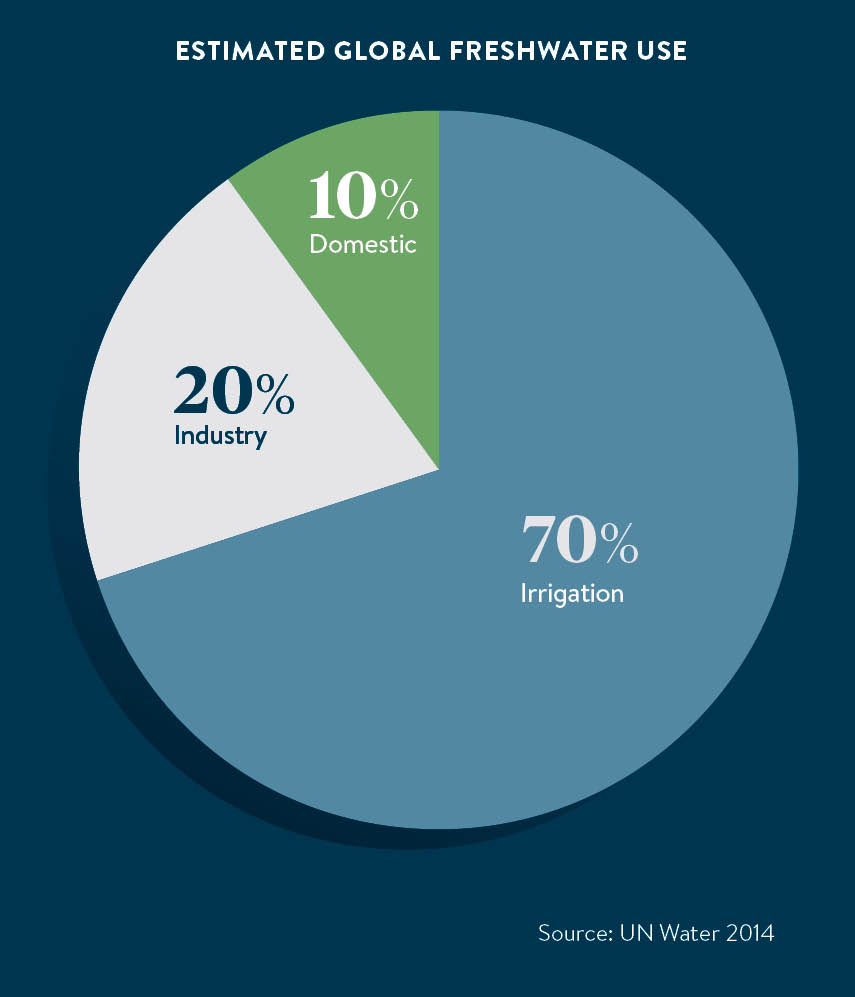

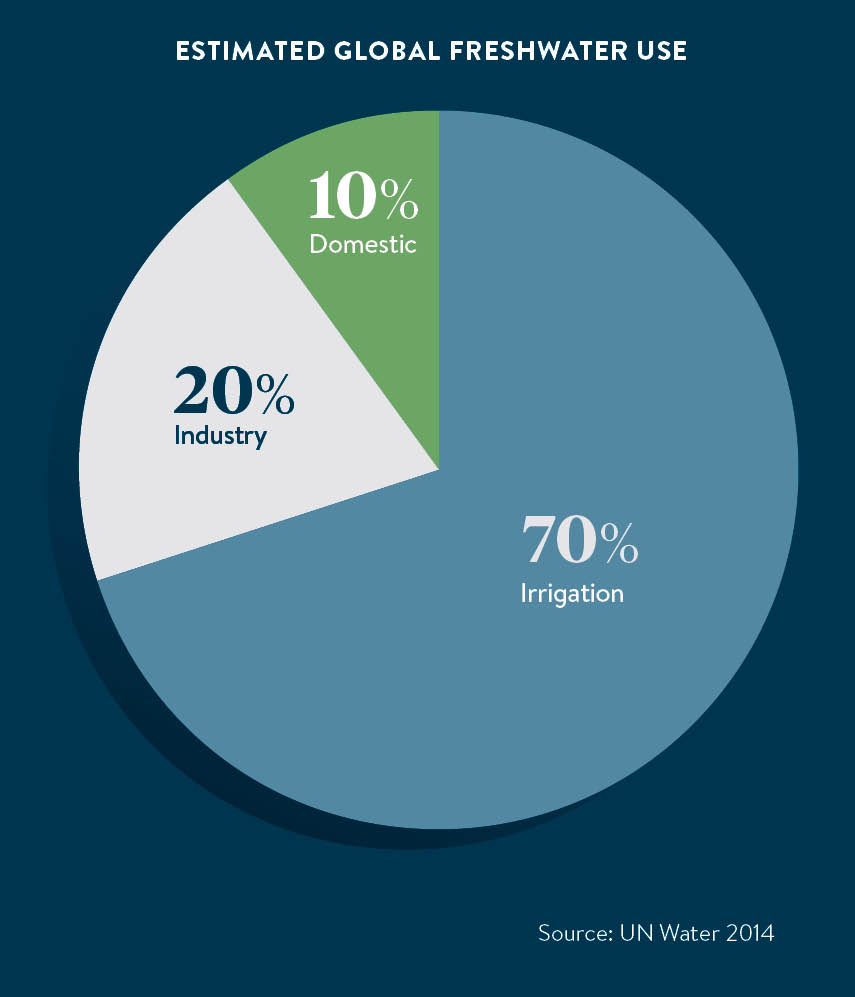

Key solutions include integrated technology applications combining water conservation and protection of catchments, plus improved water-use efficiency through such measures as recycling, as well as leak monitoring in distribution infrastructure to cut losses. In addition, ecosystems-based adaptation technologies that restore biodiversity are critical to enhancing riparian reserves that are the source of water.

Mr Fletcher also argues strongly that we should increasingly consider the context in which we operate, looking to be in tune with the water cycle and placing emphasis on the role of natural infrastructure in what will become bluer and greener cities. As well as natural capital, he also champions the importance of human capital and creative thinking. “Do not underestimate the need for leadership and an increasing dependence on social structures and community engagement as essential considerations to ensure greater resilience for all,” he says.

What businesses need to do

Leadership and engagement on water are rapidly, if belatedly, becoming issues of importance for the business community. The value of water is now an emerging metric on the balance sheet. Head of water at global environmental reporting system CDP, Morgan Gillespy, says: “The cost of inaction on water security is getting higher every year. This year companies reported $14 billion in water-related impacts through CDP, up from $2.6 billion. Companies can no longer afford to treat water as a free and plentiful resource.”

Just as happened with energy and carbon before it, water is starting to be seen as a potential performance differentiator for corporates, not just in terms of environmental impacts, but the financials of business risk and asset management.

Water is also a shared resource and companies are becoming more conscious of the local context of their abstraction and usage activities. Highlighting Ford Motor Company recycling 100 per cent of its industrial wastewater in water-scarce India, so offsetting freshwater consumption, Ms Gillespy adds: “There are signs we are on the cusp of a sea-change – companies are starting to consult and factor in wider stakeholders in water risk assessments, targets and policies.

“We are already seeing companies look outside their own walls and work collaboratively to manage water resources with governments, local communities and civil societies. And we are seeing companies work at the river-basin level, with the aim of ensuring sustainable and equitable water use for all.”

The cost of inaction on water security is getting higher every year

According to CDP, there is a great opportunity to think about water as part of climate mitigation, with 24 per cent of business actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions dependent on stable and secure supply. Encouragingly, it found 53 per cent of companies successfully reduced emissions via improvements to water management.

Joined-up thinking can drive change, concludes Ms Gillespy. “Understanding synergies between climate and water will be key to realising opportunities and securing our low-carbon future,” she says.

Of course, having your business based in the extreme near-rainless heat of the Atacama Desert in Chile can give a certain edge to your appreciation of the worth of water, as chief executive at Neptuno Pumps, Petar Ostojic, explains: “Being located at the driest place on Earth has heavily influenced us to use our scarce and valuable resources in the most sustainable and efficient way. Furthermore, we are also at the heart of the world’s biggest mining industry, which is highly intensive in the use of water and energy, motivating us to design innovative and energy-efficient pumping solutions.”

According to Mr Ostojic, mining companies in Latin America generate up to 400 tons of waste metal scrap a month. By reusing and recycling this material in up to 60 per cent of its products, Neptuno can reduce its own energy consumption and carbon footprint by 70 per cent, manufacturing pumps which help the mining industry recycle up to 80 per cent of its water, with 30 per cent less energy and carbon footprint.

This kind of resource win-win-win for energy, water and waste illustrates the opportunities that still exist even in traditional sectors. It requires innovation of mind, as much as of matter.

Water scarcity accelerating

Water scarcity accelerating

Time for change