When thinking about the future of work, it’s easy to focus on what work will be like for those just starting, or yet to start, their careers. But as the workplace changes, it’s important not to forget about the impact on older workers.

More than a third of people in the UK report having experienced ageism in the workplace and over 64 per cent of older workers are concerned about being discriminated against at work. How does discrimination in the workplace manifest itself, what can we do about it, and how do companies and human resources departments need to change their thinking about older workers?

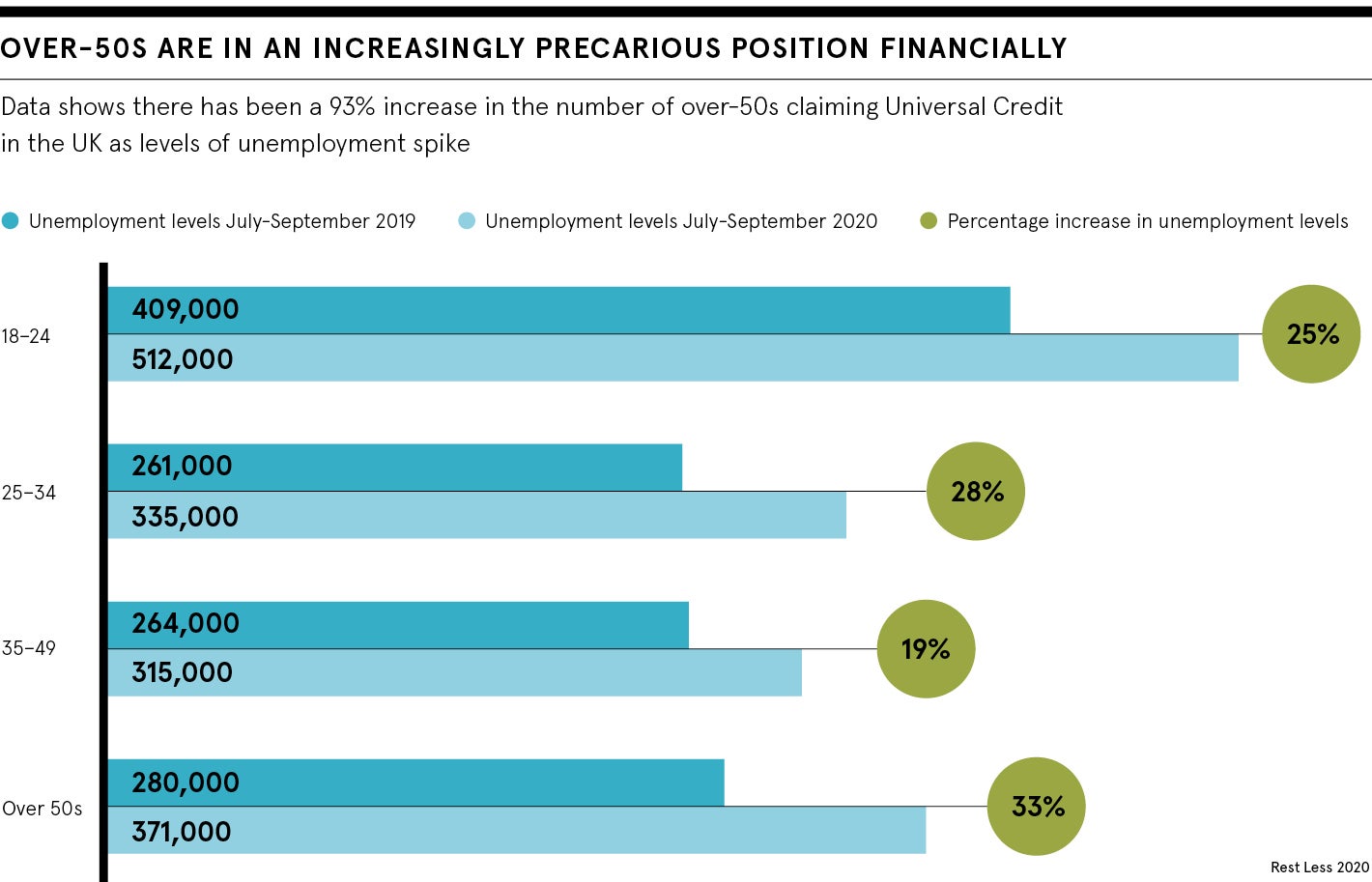

Treatment of older employees is a bigger issue than ever. While redundancy rates have risen dramatically across the board during the coronavirus pandemic, job losses tend to affect older workers more. Pre-pandemic research by over-50s website Rest Less found redundancy rates were more than double for workers in their 50s compared to those in their 40s. Indeed, over the past 12 months, unemployment has risen by a third for the over-50s and by 75 per cent for the over-65s.

Rest Less chief executive Stuart Lewis sees this as only the start. “Sadly, these numbers are simply the canary in the coal mine. With the furlough scheme winding up and 2.5 million over-50s having been furloughed, we expect this to leave a permanent scar on this generation and their employment prospects,” he says.

More older workers than ever

Beyond the immediate future, rising retirement ages will see ageism in the workplace become relevant to more of us. Already people have started to talk about the concept of “unretirement”, with retirees returning to the workforce through financial pressure or simply because changing attitudes and increasing standards of health mean they don’t feel like leaving work behind yet.

The old ideal of a job for life setting you up for a comfortable retirement by your early-60s is increasingly mythical and it’s important employers face up to the reality of what the hiring pool their staff are coming from is actually like, rather than just trying to fill positions according to a misinformed stereotype of the ideal employee.

Despite the progress against ageism in the workplace made by the Equality Act 2010, ensuring that age is a protected characteristic, some firms have a long way to go in improving their hiring practices.

During a job interview a candidate was told, ‘I’m sorry, but you remind me of my mother and I wouldn’t want my mother working here’

Victoria McLean, chief executive of career consultancy firm City CV, points to companies that try to side step the law through wording. “Loads of job ads include age-biased language,” she says. “They should be avoiding using words that suggest they’re looking for applicants from a particular age group, for example terms such as ‘two to three-years’ experience’, ‘enthusiastic young people’, ‘recent graduates’ or ‘we invite people to join our young team’.”

Interview processes need to be structured to avoid conscious and unconscious biases, says McLean, advising that all the candidates are asked the same questions and firms should be “investing in interview and assessment skills training to ensure every candidate is treated with parity and fairness”.

Lewis cites an extreme example when during a job interview a candidate was told, ‘I’m sorry, but you remind me of my mother and I wouldn’t want my mother working here’, and had the interview terminated. Companies seeking to avoid complaints of age discrimination would be wise to ensure their hiring processes have no space for such gross stereotyping to be a factor.

Training courses can revitalise productivity

Ageism in the workplace can be a real issue at the hiring stage. More than one in seven workers over 50 believes they’re been turned down for a job because of their age and nearly one in five have or have considered trying to hide their age during a job application process because they feared such discrimination. Older workers are unconvinced that employers will always take a fair, or indeed legal, attitude to how age affects someone’s ability to do a job and are behaving accordingly.

There may be a perception that older job candidates are more inflexible, less likely to have up-to-date technical skills and they’ll ask for more money compared to a younger, potentially more productive candidate. Though sadly for us all our mental and physical performance will probably decline as we get older, this doesn’t necessarily tell us much about how our performance at work will change.

Academic studies in this area have found that the knowledge gained through experience of a job, which older workers are inevitably more likely to have, is one of the most important predictors of how well someone will perform at that job.

Ageism in the workplace can play a factor in how older workers can progress in their careers. Stereotypes may affect who firms are willing to spend money training, making it harder for older workers to keep pace with the skillsets of those newer to the workforce. If productivity drops as a consequence, they are likely to face more barriers to progression and eventually face redundancy, whereas investment in training could enable them to keep pace and apply their existing experience to new situations and tasks.

By failing to hire, invest in or, ultimately, keep their older employees, employers may not only be opening themselves up to accusations of having broken anti-discrimination law, but be fooling themselves into thinking successful companies must be comprised entirely of young faces rather than looking at the potential a different kind of workforce brings in terms of knowledge and experience.

Lewis at Rest Less concludes: “If we lose this generation from the workforce entirely, we risk losing valuable key skills and key workers from the workplace for good.”

When thinking about the future of work, it’s easy to focus on what work will be like for those just starting, or yet to start, their careers. But as the workplace changes, it’s important not to forget about the impact on older workers.

More than a third of people in the UK report having experienced ageism in the workplace and over 64 per cent of older workers are concerned about being discriminated against at work. How does discrimination in the workplace manifest itself, what can we do about it, and how do companies and human resources departments need to change their thinking about older workers?

Treatment of older employees is a bigger issue than ever. While redundancy rates have risen dramatically across the board during the coronavirus pandemic, job losses tend to affect older workers more. Pre-pandemic research by over-50s website Rest Less found redundancy rates were more than double for workers in their 50s compared to those in their 40s. Indeed, over the past 12 months, unemployment has risen by a third for the over-50s and by 75 per cent for the over-65s.