In 2017 South Korea expert Professor Robert Kelly was giving a live BBC TV interview when his four-year-old daughter boldly danced into the room. Working parents around the world gasped in horror. The clip, which inevitably went viral, was the ultimate working-from-home nightmare, the equivalent of the dream where you accidentally turn up to school naked.

Yet within a week of the coronavirus lockdown, which forced schools to close and much of the population to work from home, many working parents had experienced their own comparable scene during a video conference call. The difference? No one batted an eyelid.

An enforced experiment, with added kids

With other childcare options from nannies to grandparents ruled out, there was no avoiding the fact families would be front and centre in this new home-working reality. Which, of course, has its upsides.

“One of the joyous things is the number of kids that now appear at our senior management meetings,” says Derek Jones, chief executive of luxury travel operator Kuoni. “We all know each other’s families quite well now; they were just names before.”

Some companies have run weekly magic shows for employees’ kids, others have done Star Wars quizzes and colouring contests, while Kuoni do regular show and tells. “These are moments you wouldn’t have had otherwise; it’s been really good for team morale and bonding,” says Jones, who is also grateful for the unprecedented amount of time he’s getting to spend with his own children, aged 8 and 12. He would barely see them in a normal week.

Jones is helped by the fact his wife’s business is on pause due to COVID-19, so she’s able to take care of home-schooling, but for families where both parents are still working full time, jostling over primary parenthood has been fraught.

Dr Heejung Chung, reader in sociology and social policy at the University of Kent, who specialises in work autonomy, flexibility and work-life balance, is researching the effects of COVID-19 on working parents. She says, while the quantitative data isn’t in yet, qualitative data suggests the majority of this burden is falling on working mothers.

Kids now appear at our meetings. We all know each other’s families quite well now; they were just names before

“Before coronavirus, even if both parents worked full time, when women work from home they spend around double the amount of time on childcare and housework as men,” she says, though pointing out there are exceptions and that it is by no means men’s fault.

“These are the social normative pressures that everyone is facing. It’s still considered the man’s role to be the breadwinner and the woman’s role to make sure the household is managed properly.”

Chung says this holds true even for dual high-earning couples, who are finding it especially tough to work as normal as they often rely on outsourcing housework, childcare and, in some cases, cooking.

“Based on the stories we’re hearing, these parents still fall back on those roles, with women feeling extra pressure to entertain the children and get home-schooling right, so their kids don’t lose out,” she says.

Why flexible working matters for both parents

The fallout from reverting to this traditional division of labour may be lower levels of wellbeing for mothers and a reduction in work productivity. In the long term it could lead to burnout for women, who may then look to reduce their working hours, exacerbating the gender pay gap and brain drain.

Chung points to early data, from two higher education journals, showing female academics are publishing fewer journal articles than their male counterparts due to taking on additional care duties.

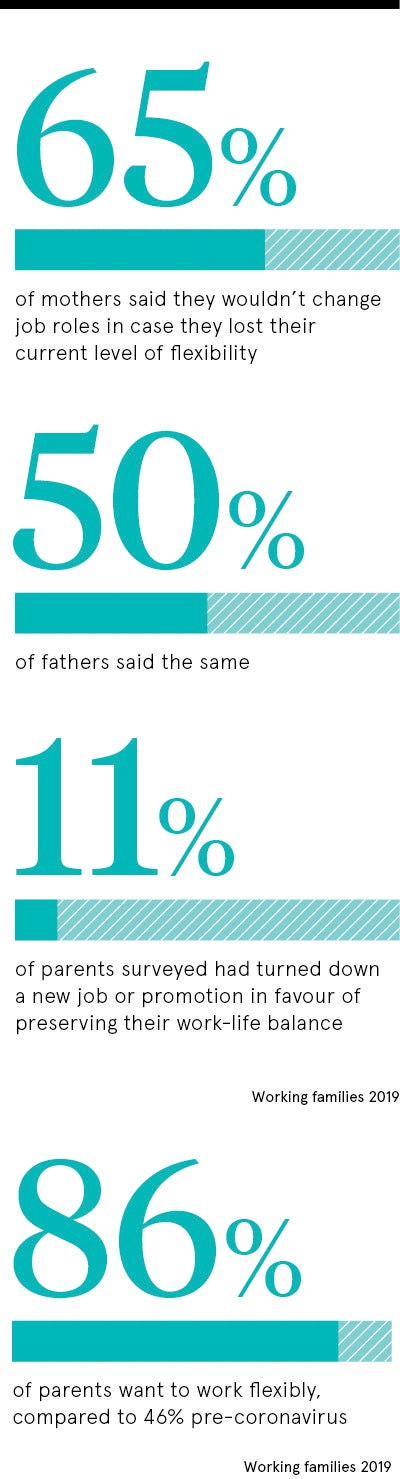

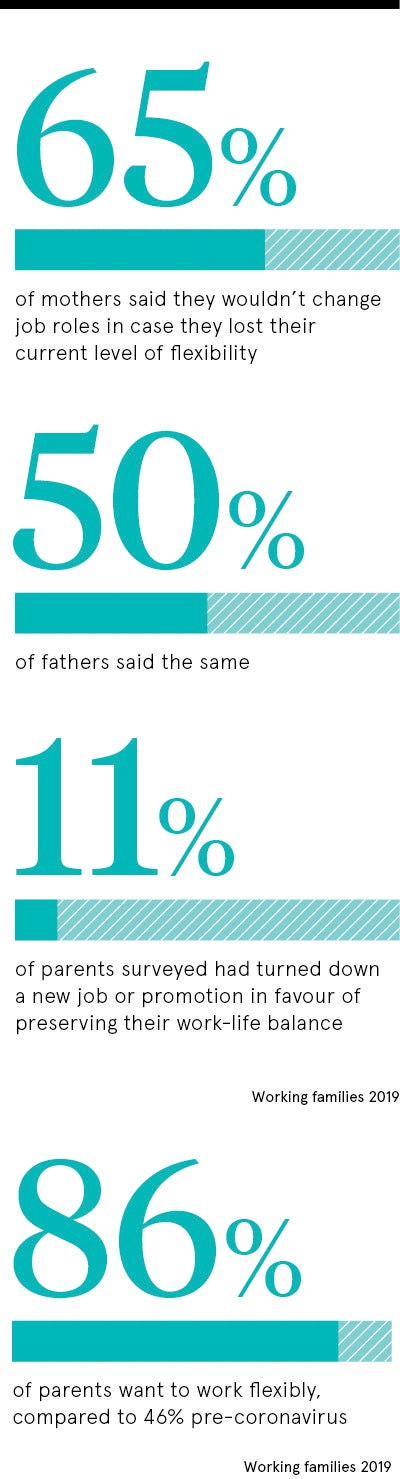

This situation isn’t great for fathers either as it can lead to dissatisfaction in the relationship. Where things appear to work best is when both working parents share the load at home and embrace flexible working. Chung’s research shows that when women work flexibly, with control over their start and finish times, they are twice as likely to keep the same working hours after having children.

At Kuoni, many of the senior management team have children. “Where both parents work full time they have found it difficult,” says Jones, who has encouraged his employees to work flexibly. “Some have started early, others work in the evenings.”

But, as everyone has taken a 20 per cent salary cut across the company, Jones has reminded staff he’s not paying them 100 per cent so if they need to take a day off to have proper time with the kids that’s fine. He reports that some men with young families have asked to be furloughed, not just women.

Chung believes part of the problem with flexible working is it’s still considered a policy for mothers. “But it’s actually a productivity policy and an employee wellbeing policy, and it’s now going to be a health policy too,” she says.

Forging a future flexible working model

Jones adds: “I find it hard to imagine going back to the old ways of working now.” His senior team have spent the last five years thinking about how to solve the problem of retail staff attrition when they have families. “These are people we’ve invested a lot in since their early-20s and now we could have the opportunity to keep them, but they work from home,” he says.

As we get more comfortable with video calls, Jones thinks customers could value travel appointments in the evening when stores have closed, as working parents may be happy to work once their children are asleep.

These conversations are going on in businesses everywhere. “It’s absolutely a reset button,” says Chung. “A wonderful opportunity to recalibrate our preferences around flexible working.”

Employers can see that many jobs they deemed impossible to do outside the office can be done and how productive their employees can be when they work from home. Plus, if they’re like this now, just imagine how efficient they’ll be once the government opens schools again and the children are out of the picture.

An enforced experiment, with added kids

Kids now appear at our meetings. We all know each other’s families quite well now; they were just names before