Until recently, staff at ClearScore, the credit checking firm that has grown from zero to 105 employees in just over two years, were so tightly crammed, desks were only 80cm wide to save space.

“We were packed,” admits founder, Justin Basini, who in February finally moved everyone to a larger, 8,500sq-ft office in Vauxhall. Although not perfect at first – he says “now it’s messier, more higgledy-piggledy and generally noisier” – this chief executive says he wouldn’t have it any other way.

“As a mission-driven business, our office is our congregation. We couldn’t create the energy and passion without it. We’ll continue to grow, but we’ll always have a central workplace; it just works,” he says.

While it may not seem it, in many ways this is a remarkable vote of confidence for organised workplaces. With UK plc languishing almost bottom among G7 countries for productivity, offices have suffered their fair share of ire; everything from them breeding distraction, less uninterrupted time and more presenteeism.

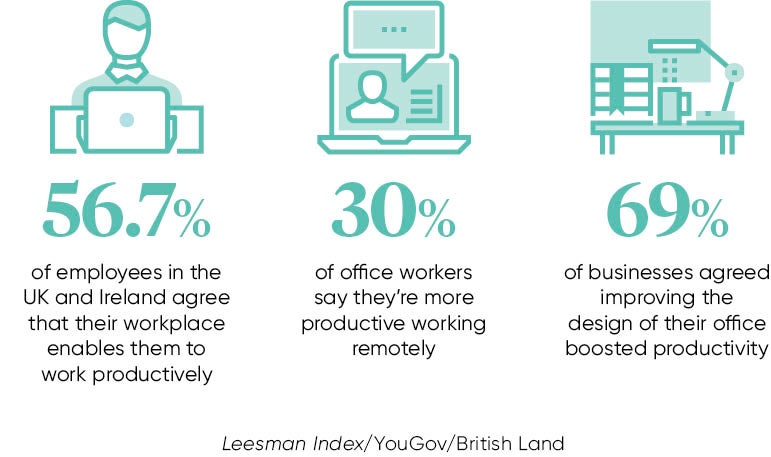

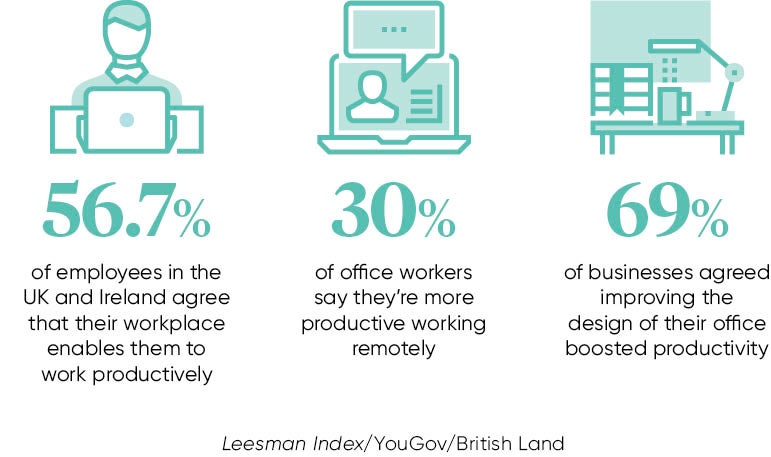

At the same time, studies point to greater happiness and productivity anywhere but the corporate headquarters. According to a YouGov poll last year, 30 per cent of office workers say they’re more productive working remotely. As such, some have chanted the office as we know it is dead. So why is it that with Mr Basini and many other bosses, the workplace still commands such authority?

The new workspace

“The ‘workplace’ is still very relevant,” argues Olly Olsen, co-chief executive at The Office Group, owner of than 1.2 million sq ft of office space in London. “Its purpose though, is changing. Where cost and location were king, now bosses are asking whether workplaces fit their brand, whether they reflect the people who are going to be there and whether they work for the community. The workplace is reinventing itself as a place where people enjoy working.

“Google’s plans for its upcoming London HQ really showcase this. I can’t remember a time when a workplace was written about purely as an exciting place to be.”

The flipside, however, is that this expanded purpose does make it even harder for workplaces to prove a return on investment (ROI), just when many claim the workplace needs to be scrutinised more by the C-suite. If firms are to accept a productivity dip by having all their people in one place, they need to know that their workplace really does create the tight culture and innovation, or attracts the best talent, that more than makes up for this.

“This is the conversation that still needs to happen,” says Dr Mark Batey, senior lecturer in organisational psychology at Alliance Manchester Business School. “Can organisations have a common purpose without a workplace? The answer is probably no, but my feeling is while the workplace still has a role, workplaces are trying to do too much. People don’t need to travel to a workplace just to do the procedural stuff, on their own.

“Workplaces should really be used for just one thing – collaboration and meetings. Employers setting aside 40 to 60 per cent of their workspace for ‘quiet’ areas aren’t using their space efficiently. This is the sort of conversation boardrooms need to start.”

It’s a view not all agree with. “The workplace isn’t dead, it’s critically important, and we believe workplaces should be designed to accommodate all types of work,” says Josh Krichefski, chief executive at media agency Mediacom. The agency actually launched flexible working for all last year, effectively rubber-stamping the fact that the office doesn’t need to be employees’ first destination.

The workplace is reinventing itself as a place where people enjoy working

But while some might argue this means Mr Krichefski is hedging his bets, he says not: “What modern workplaces need to offer is a choice about whether staff want to be at the office or somewhere else. But when they are here we must ensure it’s a place they want to be.”

In May, the British Council for Offices produced its Corporate Culture report which reiterated the then-findings of the Leesman Index that 53 per cent of staff did not yet think the workplace they’re in makes them productive. Reasons include noise, lack of variety of workspaces, such as breakout rooms, quiet areas and communal zones. However, if these were addressed, it said workplaces could boost productivity by up to 3.5 per cent.

So can they?

Well, what might change the conversation is new research that is beginning to question just how draining offices are and just how sustained the productivity of remote or homeworking is.

“Our research actually finds people are no more or less productive at home than in the workplace over time, because once homeworking is normalized, the novelty wears off,” argues Dr Esther Canonico, fellow at the London School of Economics’ Department of Management.

“We also find homeworking creates social exclusion and lack of promotion. Those who work at home or remotely aren’t given the opportunities office workers get, simply because they’re not there and are less visible.”

While employers do believe there is more to workplaces than just productivity, the good news is productivity is rising up the agenda. “Our research shows 75 per cent of businesses consider the productivity implications of their office,” says Joff Sharpe, head of operations at British Land. The same study found 69 per cent of businesses agreed improving the design of their office boosted productivity.

Planning how much overall space they’ll need though will become a growing ROI headache for employers who still want a destination workspace, but also want to promote flexible working.

And it’s still the case that other issues, such as having up-to-date technology, need tackling too. IDC recently found 34 per cent of staff were not satisfied with their at-work technology. If this does drive people away from traditional workplaces, they’ll be sure to miss the workplace culture and vibe.