Not so long ago, it seemed as though normalising flexible working and slashing the nine to five were dismissed as welcome but unfeasible options for many employers, with one in three flexible working requests rejected in 2019, according to the TUC.

But as the government plans to end the furlough scheme in October and the country faces its worst recession since records began, rethinking the way we work is non-negotiable. It’s also become increasingly clear that working full time is neither preferable for everyone, nor a necessity.

That’s where job sharing comes in. Far from a new phenomenon, John Lewis, Lloyds Banking, the BBC and the Green Party are just a few of the organisations with leaders taking on joint roles on a part-time basis. As research shows that job-sharing schemes could be the key to saving millions of jobs lost in the coronavirus pandemic, is it time to make job sharing the norm?

How job sharing could save jobs

While the benefits of job-sharing schemes have been touted by economists, policy-makers and employees for years, the idea has still failed to become a reality for the majority of workers.

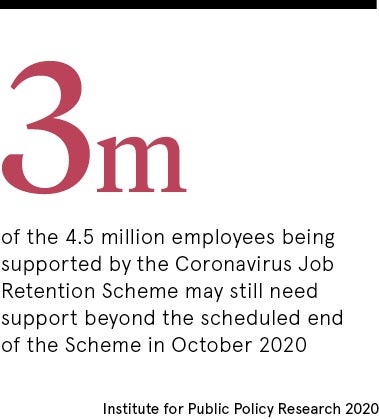

There’s a strong argument for why this should change. A report by the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) in August suggested that job sharing could be a lifeline for millions of employees at risk of losing their livelihoods as a result of COVID-19 as the furlough scheme winds down.

“The chancellor has said he will never accept unemployment as an unavoidable outcome. But by ending the Job Retention Scheme too early, and with no plan for protecting jobs in local lockdowns or a second wave, that is precisely what is happening,” says Clare McNeil, IPPR associate director for work and the welfare state.

“Up to two million jobs could be lost, not because business owners are not working hard or smart enough, but because of continuing social-distancing measures.”

[Job sharing] could pay for itself, as it keeps people in work… and so would sustain the economy’s productive capacity

In response, the think tank urged the government to introduce a coronavirus work-sharing scheme, through subsidising part-time work at a rate of 10 per cent.

Coupled with an overhaul of the universal credit system, IPPR’s report claims the move could save around two million jobs: “It could pay for itself, as it keeps people in work, helps support incomes, both now and in the future, and so would sustain the economy’s productive capacity,” says Carsten Jung, senior economist at IPPR.

Is job sharing better for work-life balance?

Beyond the immediate economic benefits, one of the more obvious draws towards job sharing is its potential to improve work-life balance.

The civil service, which launched an online portal to help its workforce into job-sharing schemes, noted that those with disabilities, people looking into partial or phased retirement, and those with caring responsibilities could all benefit from job sharing.

Sue Beaumont Sate, civil service senior policy adviser, found that working in a job-share scheme made it easier to keep on top of her workload as a parent and improved her productivity overall. “As a working mum with a long commute, I found working as part of a job share not only meant that I wasn’t coming back into work at the start of the week to an overwhelming inbox, but it also enriched the work I delivered and my job satisfaction,” she says.

“It definitely improved our productivity, creativity and commitment to success in that role. It also enabled us to balance a stretching job with caring commitments.”

Beaumont Sate is far from alone. The Timewise 2020 Power 50 list, which features leaders in part-time roles, included seven senior employees from sectors as diverse as banking, healthcare and media.

How sharing a job can widen its scope

Others are keen to emphasise that while job sharing can be incredibly rewarding, it shouldn’t just be seen as something that can improve work-life balance.

For Dr Jo Yarker and Dr Rachel Lewis, who are both academics at Birkbeck, University of London and directors of Affinity Health at Work, a research consultancy, job sharing allowed them to embark on portfolio careers and take on more challenging work.

They can also be super for people who want to work in different organisations and blend different skills

Yarker explains that it’s important not to pigeonhole job sharing as something that’s just taken on by women with caring responsibilities. “For us, we love our academic careers and our consultancy work, and we’re not keen to give either of those up. Typically, when we think of job shares, we’re largely thinking about women who want to spend part of their life with children,” she says.

“They can also be super for people who want to work in different organisations and blend different skills. It’s a chance to really enrich people’s careers. This could be relevant to millennials too, who have shown they’re keen to take up different areas of work.”

How can you ensure sharing schemes work?

While Yarker and Lewis have found they’ve been able to work together seamlessly, it’s easy to see how job sharing could be an altogether more daunting prospect for others. What if one person isn’t pulling their weight, for example? How can you tell your job partner that you’re not happy to answer emails at weekends?

Without careful planning and regulations in place, job shares could quickly descend into miscommunication and conflict, causing tensions in teams and a host of problems for human resources departments.

Open conversations about priorities and pressure points have both helped the two colleagues to make their working relationship a success, but much of it comes down to being able to trust each other. “The overriding thing is mutual trust. We both do a good job and have the same aims in mind, so even if we go about things in a different way, we both know we’re working in each other’s interests,” says Yarker.

Rather than job sharing creating problems, it seems like it could only exacerbate existing issues or strengthen working relationships that are already fruitful. And if the cracks in your team are starting to show, then isn’t it time to fix them?

Not so long ago, it seemed as though normalising flexible working and slashing the nine to five were dismissed as welcome but unfeasible options for many employers, with one in three flexible working requests rejected in 2019, according to the TUC.

But as the government plans to end the furlough scheme in October and the country faces its worst recession since records began, rethinking the way we work is non-negotiable. It’s also become increasingly clear that working full time is neither preferable for everyone, nor a necessity.