When companies in regulated industries wrote their business continuity plans, nobody imagined a scenario where all their offices would be shut at the same time and nearly all employees would be working from home.

While many organisations had already started exploring the potential for remote working before the coronavirus hit, regulated businesses have found it more of a challenge, given compliance controls mean some roles are not naturally suited to home working.

“Regulatory regimes definitely introduce a whole additional overlay of things that businesses need to worry about,” says Peter Bevan, global head of Linklaters’ financial regulation group.

“Financial services are subject to detailed regulation by the Bank of England and the Financial Conduct Authority, and it gives rise to two separate sets of issues. One is that working remotely can make it difficult to comply with specific regulatory requirements and second it introduces new types of risk into your business which you might not have previously accepted.”

An issue for investment banks, for instance, is maintaining effective supervision of traders, such as monitoring for market abuse and recording certain types of communications, he adds.

In other regulated industries, such as insurance, a challenge around remote working is protecting customer data. Danielle Harmer, chief people officer at Aviva, says this has meant ramping up risk-mitigation measures.

“In an ideal world, would you have colleagues speaking to customers over the phone at home, probably not. But you have to make decisions about risk,” she says. “From a mitigation perspective, we’ve said no paper can leave the office with any data on it and we’ve found new ways of making sure we can approve things remotely.”

Tackling risk management concerns

Law firms have a similar issue. Susan Bright, managing partner of Hogan Lovells for the UK and Africa, says client confidentiality is key.

“People have to think about their home-working environment like they would the office in terms of what can be seen on computers and destruction of documents and so forth after you’ve been using them,” she says.

Regulated industries that handle customers’ money are also finding remote working a challenge. Danny Cox, head of communications at investment service Hargreaves Lansdown, says some clients still send cheques through the post.

“You still need to have people in the office to be able to open post and bank cheques,” he says. “If we had to go to full quarantine measures and nobody was allowed in the office at all, then we’d have to rethink how we deal with cheques remotely and I don’t think anyone in the industry has really got an answer for that yet.”

While much of the shift to remote working has meant regulated industries have had to invest heavily in technology, some human resources experts believe tech limitations are not the main reason why organisations were slow to roll out flexible-working programmes prior to the COVID-19 crisis.

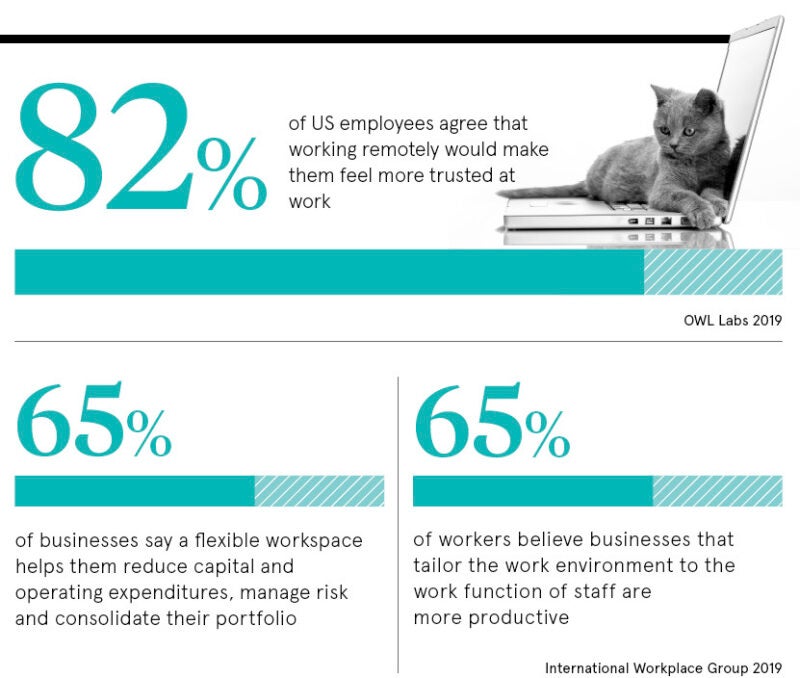

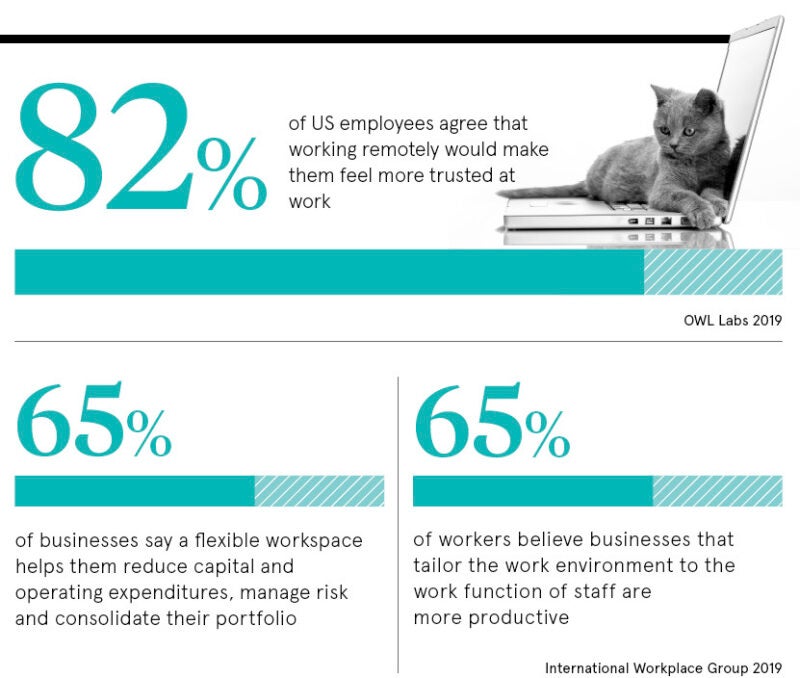

“Typically, what drives decisions around employee requests for flexibility is the extent to which there is trust embedded in that relationship and managers on the whole have preferred to reject claims for flexibility,” says David Wreford, partner in Mercer’s workforce and careers business.

“What the COVID-19 situation has done is force organisations to trust their employees to work from home, so this is a massive pilot study questioning some of the attitudes that have historically existed and driven a reluctance to allow people to work remotely.”

Embracing working from home

For some businesses in regulated industries, however, the pandemic has helped speed up a transition to more flexible working patterns. Rose Thomson, chief HR officer at Standard Life Aberdeen, says her firm has been talking about flexible working for the past 18 months. In part, this is because the company recognises people are more engaged and committed when they are allowed to work in a way that suits them, but also because it can help support diversity and inclusion.

“This has probably accelerated maybe two years’ work from an HR perspective to getting people more used to working from home and to understand presenteeism isn’t necessary to get work done,” she says.

Harmer believes attitudes will also change at Aviva now people have seen many of the firm’s roles can be performed remotely.

“Our starting point has always been that we will consider any job to be worked flexibly, be it part time or from a different location, but people will be a bit more alert now to the art of the possible,” she says. “Some parts of it you might want to unravel, but some of it you might want to reinforce. We don’t need to demand people are in an office every day.”

Hogan Lovells has had a global agile working policy in place for the past four years, though Bright says its acceptance has varied across offices globally, something she expects will now change.

“We are in the middle of a project to find new premises for Hogan Lovells in London from 2026. We’ve shortlisted a number of buildings and I am pleased we haven’t signed on the dotted line because I think we may take the opportunity to think further about how we want to work, and the amount and type of space we need,” she says. “I see a potential for a seismic change in the way businesses may choose to operate going forward.”

Tackling risk management concerns