The coronavirus pandemic has turned work on its head with millions swapping everyday office life for working from home, but how long can this new working pattern last?

During the summer, the UK government made a strong attempt to persuade employees in England to return to work if the right COVID-secure protocols were in place. Just weeks later it abandoned a follow-up ad campaign as cases of Coronavirus began to rise.

Then just last week, in an address to Parliament, Boris Johnson was forced to return to the advice given early in the pandemic, telling “office workers who can work from home to do so”. However, he also added: “In key public services – and in all professions where homeworking is not possible, such as construction or retail – people should continue to attend their workplaces.”

Confusion over return to work messaging

Such conflicting messaging has led to confusion among employers and employees, not least those fearing for their jobs and livelihoods as the prospect of redundancies grows. This is now compounded by Chancellor Rishi Sunak’s unveiling of the new Job Support Scheme to replace the current furlough scheme on November 1, something described by him as “to support only viable jobs”.

Now in the face of the current second surge of COVID-19 cases, many employees remain fearful about social distancing when commuting or working close to colleagues.

In all four nations of the UK the advice is now to work from home if possible, something that had always been the case in Wales. In fact, the Welsh government had previously tweeted its longer-term hopes for such an ideal saying: “We think this is an opportunity for a permanent change. Our aim is for 30 per cent of workers to work from or near home. This will reduce traffic, support local businesses and provide flexibility.”

A number of major companies were still embracing home working anyway, including Google and NatWest, while across professional services, such as the legal, accountancy and financial services sectors, others had continued to encourage it given many people saw personal benefits to their lifestyles.

So where does this new approach leave bosses and workers in the short, medium and long term? How viable is it to keep the return to work on hold and instead focus on remote working?

Government advice “misses the point”

Chris Herd, chief executive of Firstbase, a platform for companies to supply and manage physical equipment for remote teams, says a third of companies he speaks to are getting rid of the office entirely, with others expecting employees will work from home two to four days a week.

A Twitter thread he wrote about the 2020s being the “remote work decade” went viral with thousands of likes, and Herd insists government advice is focused on the wrong future. He says: “Workers everywhere have thrived during the most difficult conditions imaginable. The government should be looking at remote work as an opportunity for mass benefit: better work-life balance, closer relationships with family and friends, reduced pollution through the reduction of commuting, and increased inclusivity, diversity and accessibility of opportunity.

“The economy will likely redistribute to wherever remote workers happen to operate from, leading to a renaissance of smaller cities and towns. Remote work isn’t just about the future of work, it’s about the future of living.”

This view is backed by Opinium Research on behalf of Ricoh Europe, which found 53 per cent of the public believed the traditional office space would no longer exist in ten years; in September 2019 it was 24 per cent. Seven in ten also thought remote and flexible working terms will be written into more contracts in the future.

But Nicola Downing, chief operating officer of Ricoh Europe, believes a blended approach would eventually be logical, where staff can choose how to return to work, splitting their working time between the office and elsewhere. She explains: “I’ve fully appreciated the extra time with family and lack of commute, but we must remember not everyone has had the same experience. For most people, the office is undoubtedly the place where they’re at their most social, spontaneous and effective.

“Leaders must equip them with the right technologies and processes so they can be connected, productive and dynamic from anywhere.”

A full return to the workplace appears unlikely

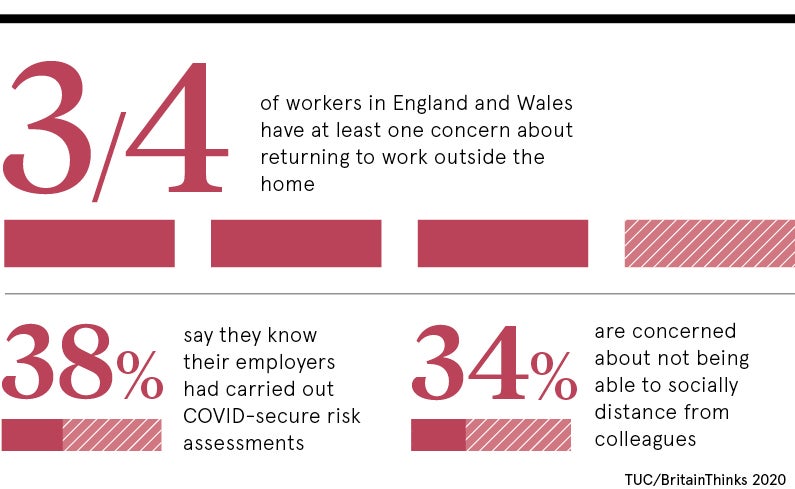

However, even before the government’s latest guidance, a poll by the TUC released in early-September showed how three quarters of workers had at least one concern about returning to the workplace, with 34 per cent citing social distancing as a factor.

Meanwhile, a separate study by TUC and BritainThinks found that just 38 per cent of workers said they knew their employers had carried out COVID-secure risk assessments ahead of the return to work.

When speaking to Parliament on September 22nd, the prime minister appeared to give one indication of countering this on a wider scale. He explained how retail staff would have to now wear masks and that Covid-secure guidelines within retail, leisure, tourism and other sectors would become a legal obligation.

Steve Vatidis, executive chairman at Smartway2, a smart buildings company helping organisations to adapt workplaces, believes ensuring workplaces are safe, clean and adhering to guidelines can be possible with the right technology in place. He said: “The new normal may be easy for a small office of ten, but for offices with over a thousand staff, multiple floors and various meeting rooms, it’s a logistical nightmare.

“Understandably, some employees will feel wary of returning. Businesses need safety nets of advanced monitoring to ensure social distancing, hygiene and contact tracing of staff, which can help workers feel comfortable to venture into the workplace.”

Taking vulnerable people into account

However, with the Ricoh Europe research also showing 26 per cent of people had felt pressured to return to work at the office, Jason Braier, an employment and discrimination barrister from 42 Bedford Row Chambers, explains there are legal risks in adopting a “come back or there will be consequences” approach.

He says: “Older employees and those with disabilities may be most resistant to returning to the office out of fear of catching the virus. Dismissing them, or subjecting them to detriment for refusing to return, places the employer at risk of various discrimination claims.

“Statutory protections are also in place for employees who genuinely fear being at work would place them in danger of catching coronavirus and arguably for those whose refusal to attend stems from fears they might catch the virus when commuting.

“Employers should treat concerns with sympathy and work together with staff to reach an acceptable solution rather than taking drastic action they might later come to regret.”

The coronavirus pandemic has turned work on its head with millions swapping everyday office life for working from home, but how long can this new working pattern last?

During the summer, the UK government made a strong attempt to persuade employees in England to return to work if the right COVID-secure protocols were in place. Just weeks later it abandoned a follow-up ad campaign as cases of Coronavirus began to rise.