You wait ages for one and then, like metaphorical London buses, two come along at the same time.

The February announcement that Norton Rose Fulbright and New York-based Chadbourne & Parke were to merge came just three weeks after Eversheds announced plans to join forces with Atlanta’s Sutherland Asbill & Brennan.

The alliances will leave Norton Rose Fulbright (the Chadbourne name has been dropped) with 4,000 lawyers located in offices in 32 countries and Eversheds Sutherland with 2,700 lawyers in 36 offices worldwide.

So, is this just coincidence or are we about to see a whole raft of transatlantic law firm mergers floating into view?

Tony Williams, principal of legal management consultants Jomati, suspects not. “I think we may see a few,” he says, “but I’m not expecting a rush.”

History suggests he will be proved right. Those with long memories can cast their minds back to the excited predictions that followed Clifford Chance’s merger with New York firm Rogers & Wells in 2000. It was a deal The Observer newspaper equated to The Beatles arriving in New York in 1964, setting the scene for a British invasion. Things didn’t quite turn out like that, however. The deal famously failed to live up to expectations, with issues over remuneration and partnership structures to the fore.

While a successful merger between a magic circle firm in the UK and a major New York-based firm could be a game-changer, it remains decidedly unlikely. Such highly profitable firms would need to find pressing reasons to overcome the inevitable issues of conflict and integration.

But the idea of transatlantic alliance might look considerably more appealing to those a little further down the legal pecking order.

A lawful alliance

Mr Williams explains: “Quite a number of US firms can see the benefit of allying with an international partner because it widens their own client base and attracts international clients into the United States. A lot of US firms have been in London for quite a long time, but have had very little impact. If they can find a suitable merger that could be very beneficial, but the number of suitable merger candidates is quite small.”

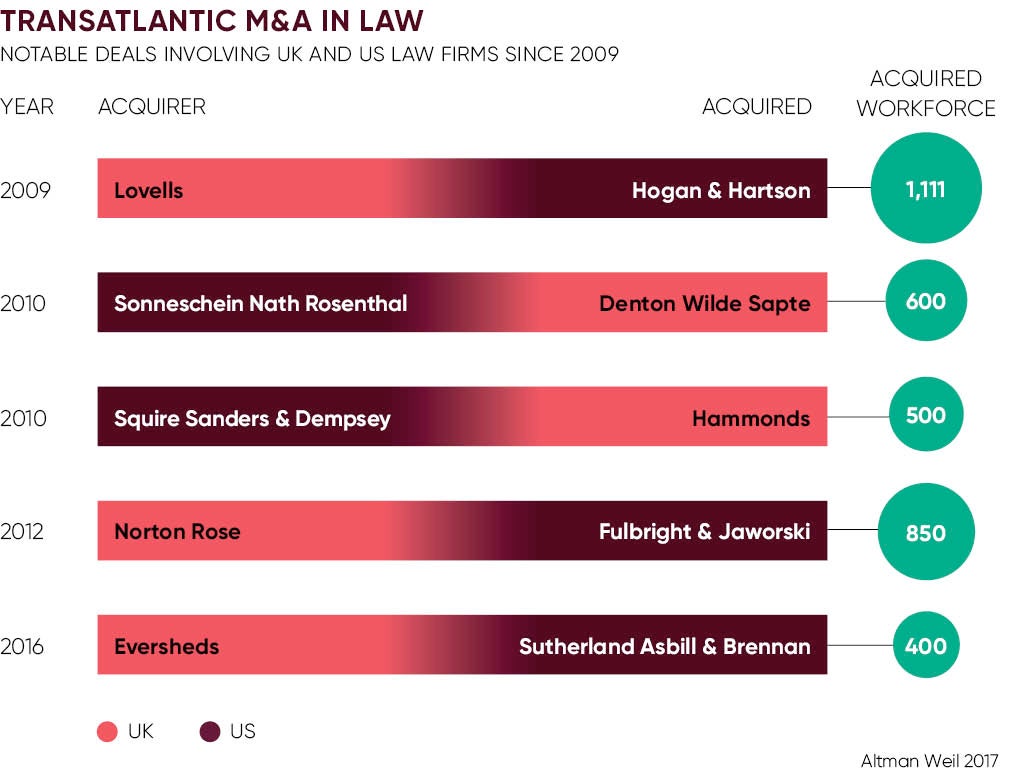

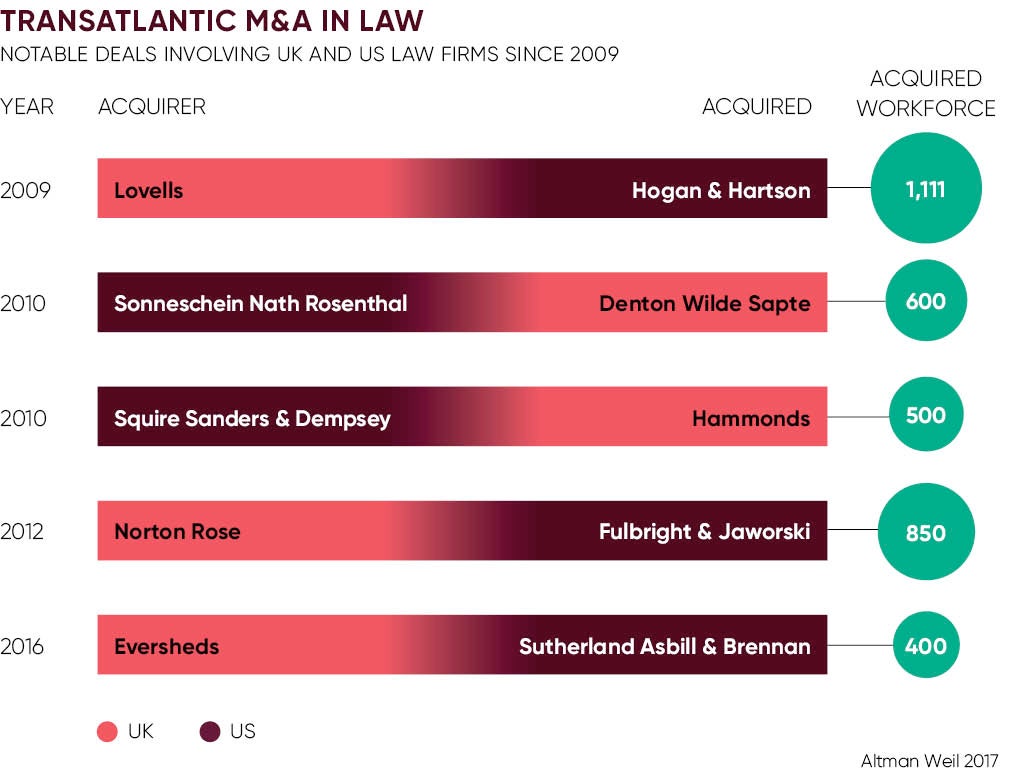

One reason for this dearth is the number of firms that have already merged, particularly since the financial crisis of 2008. According to legal consultancy Altman Weil, there were 85 deals that involved at least one US law firm with two or more lawyers in 2016 alone, slightly slightly down from the record 91 in 2015.

Tom Clay, a principal at Altman Weil, is another who believes February’s merger announcements will have set law firm partners pondering on both sides of the Atlantic.

Quite a number of US firms can see the benefit of allying with an international partner

“In the US these mergers may be viewed as an accelerator,” he says. “Other, similar firms to Sutherland, for example, will start to look around and wonder if they are now disadvantaged and whether they should be thinking about doing something similar. From that perspective I think it has generated a good deal more strategic thought.

“Sutherland’s competitors may be looking on with interest and a little envy. That was a really good, old-line law firm and now all of a sudden it’s part of a behemoth. I think we will see more people taking a serious look at that kind of strategy.”

Why merge?

Partners will be thinking about issues such as securing market access that they could never achieve through organic growth, locking in clients by avoiding referrals, and adding elusive market share worldwide. Mr Clay suggests all these factors would appeal to a tranche of US firms that, while they may feel they are doing well at the moment, do not want to become complacent.

They will also be aware that transatlantic tie-ups can flourish; witness Hogan Lovells, formed in 2010 by Lovells and Washington-based Hogan & Hartson.

Richard Tromans, a London-based legal profession analyst, says there’s plenty to be learnt from that deal. “It was a very carefully put-together merger,” he says. “Hogan & Hartson was international, but it didn’t have a huge collection of international offices. It was a win-win. The deal didn’t create any cannibalistic impact between the two firms. Yes, there were some differences in profitability, but those have been steadily addressed.

“Both parties understood very clearly what the benefits were and they fitted together well. They weren’t elite firms, but they were very good firms and they had a cultural similarity. They both did a lot of litigation and regulatory work, but there wasn’t a huge overlap.”

Jomati’s Mr Williams agrees that having defined goals is vital to making a success of a merger, especially one that spans the Atlantic. He concludes: “It can be difficult for those involved to understand the differences, from the approach to clients, to remuneration, to culture. All these factors need to be worked through and the firm needs to be very clear about what it’s offering to clients that others aren’t. More and more firms have developed US-UK capability, so you have to be able to achieve something that is compelling.”