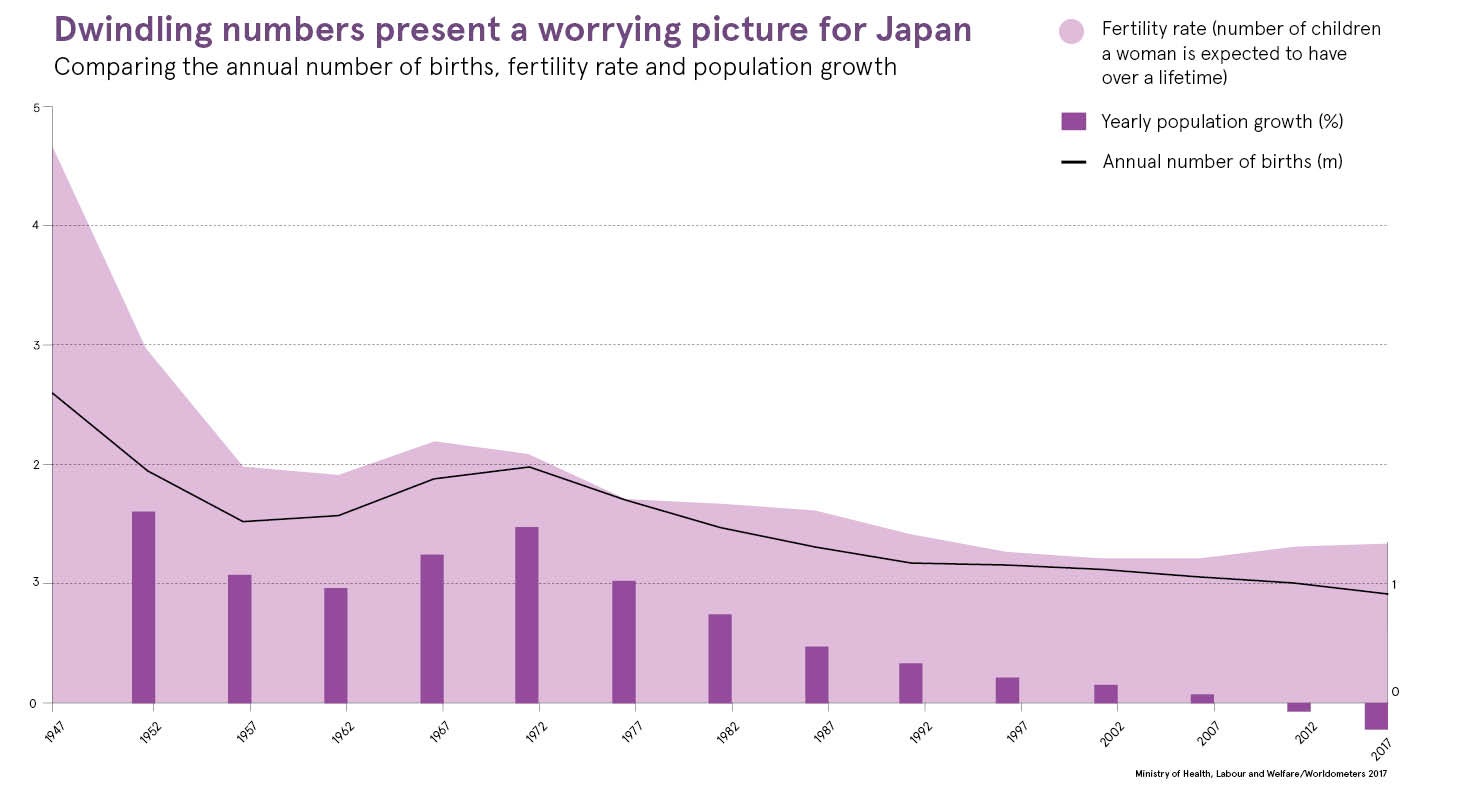

All is not well in the Land of the Rising Sun. Japan, a country whose gross government debt as a proportion of GDP rose to 253 per cent in 2017, faces the dual challenge of an ageing populace and dwindling births.

If left unsolved, these twin issues will squeeze Japan’s shrinking workforce with the burden of paying for the old and young. Combined with a low fertility rate of around 1.4, which represents the number of children that an average Japanese woman will have in her lifetime – a sustainable rate is 2.1 – Japan’s rising costs will have to be paid by an ever-smaller proportion of workers.

“There is a terrible labour shortage in Japan,” says Dr Randall S. Jones, head of the Japan and Korea desk at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). “Companies are starting to cut back their services, restaurants close early, delivery services won’t cover parts of the country.”

According to Dr Jones, if fertility rates do not improve, Japan can expect its population to fall from around 128 million at present to 98 million by 2050. As that happens, the proportion of elderly people aged over 65 will increase from about 26 per cent now to 45 per cent at the mid-point of the century.

Low fertility rates, coupled with ageing populations, are testing nations across the Far East

As a result of the country’s rapidly ageing population, April saw credit rating agency Moody’s warn of near-term and long-term credit challenges, as well as slower GDP growth, caused by lower household savings, a narrower tax base and rising welfare costs.

“We’re talking about losing 30 million people – the situation now is very dramatic,” Dr Jones says. “We’re not going to be able to stabilise the population for quite some time. It’s a very stark picture.”

Aware that time is of the essence, prime minister Shinzo Abe has focused considerable effort on persuading Japanese families to up their game when it comes to baby-making. While Japan has seen its fertility rate grow since a low of 1.3 in 2005, Mr Abe is going to have to hope he can persuade his citizens to get on board if the country is going to meet his fertility rate target of 1.8.

To facilitate this, Japan’s government has tried a number of different initiatives. Examples include the Plus One Proposal, which has tried to encourage Japanese families to grow by “plus one”, as well as the Angel Plan and the New Angel Plan, which were used to make having children easier and more attractive. Incentives included boosting the number of childcare places available throughout the country, with free childcare for infants aged three to five years old.

Japan has also doled out cash payments for new mothers. However, this can’t be extended to paying women to take care of their own children, as Japan still needs to address its impending labour shortage.

“Giving people money to have babies, like an allowance, makes women less likely to work,” says Dr Jones. “If they get money for having babies they don’t have to work, and the government wants them to work and have babies.”

Another thing that needs to be tackled to kickstart a baby boom is Japan’s culture of workaholism, which is so severe that karoshi – literally death by overwork – is now an infamous phenomenon. Dr Jones says the government is currently considering legislation that would cap the total amount of overtime a worker could do at 100 hours a month, limited to 720 hours a year. By reducing the number of hours that people can work, Japan is trying to improve work-life balance and free people up to spend more time with their families.

So far, initiatives to boost Japan’s fertility rate have had limited success, at least according to a case study published by the Centre for Public Impact. The organisation says that while Japan’s fertility rate has increased, it continues to lag behind the OECD average of 1.7.

What’s more, despite even limited success in growing fertility rates, the Centre for Public Impact also found that the number of women of child-bearing age leaving the labour force has increased; the exact opposite of what the Japanese government is hoping to achieve. With day-care waiting lists in the 20,000s, it is unlikely that returning to work for many young mothers will be an option any time soon.

One more side effect is that if the baby boom really does take off, the first two decades are going to see the working population come under immense pressure. “The first 15 to 20 years, if they did get a rise in the number of babies, would be even more difficult,” says Dr Jones. “That would be a short-term transition to a steady equilibrium, but would mean more spending on education.”

Whatever Japan’s future, the country is not alone in facing such problems. Low fertility rates, coupled with ageing populations, are testing nations across the Far East, including Taiwan and South Korea.