-

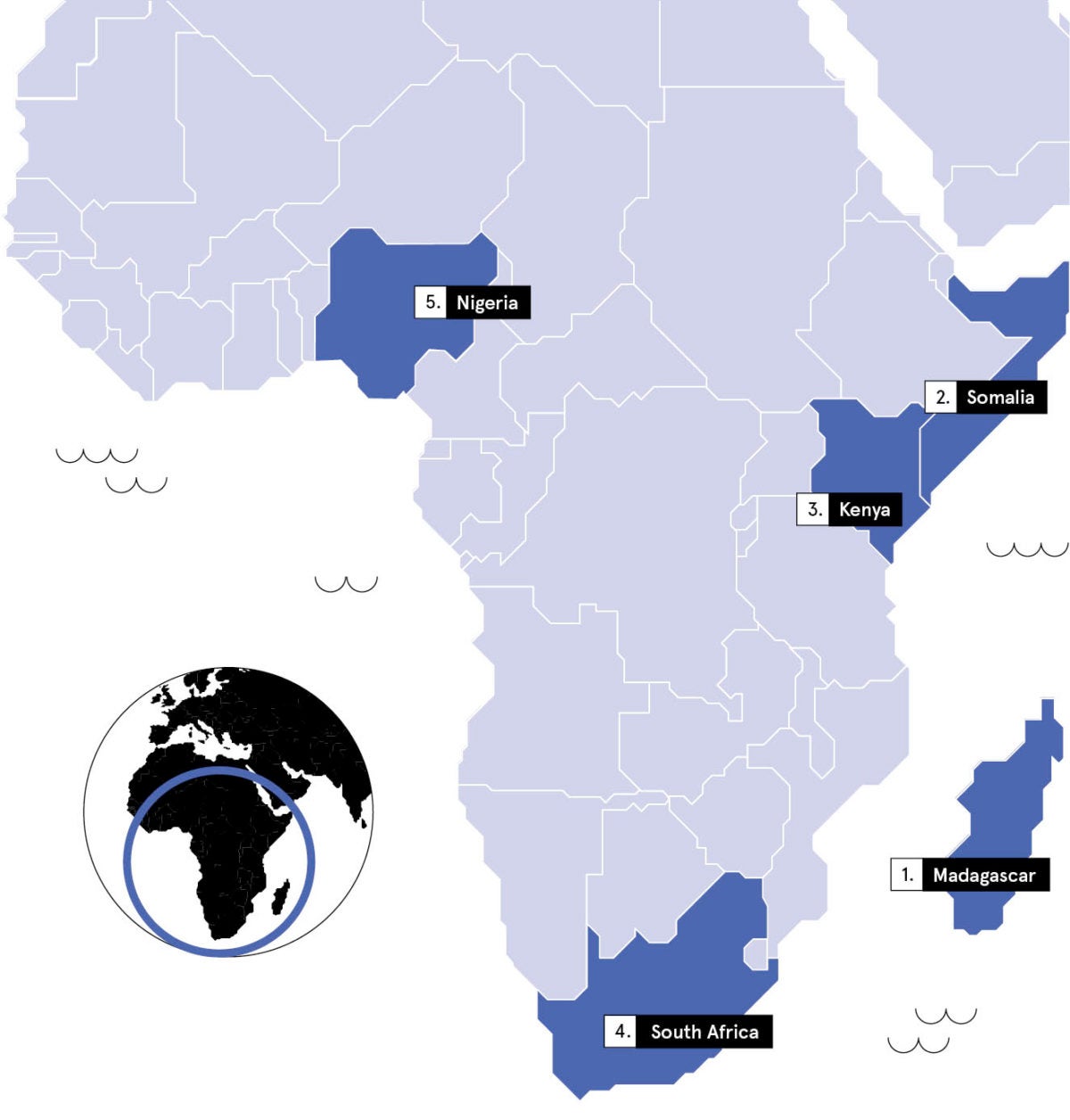

Madagascar

With a 5,500-kilometre coastline, Madagascar’s potential to benefit from a blue economy is huge. This was identified by the Malagasy government in 2015 when it determined that a clearly defined set of blue-economy principles could be the way to jumpstart economic development in the country.

Historically, the majority of the population has focused on agriculture to earn a living, but the island is perfectly placed to profit from maritime transportation as it sits in a prime position on the Indian Ocean trade route that links Australia, Asia and the Middle East.

From shrimp fisheries in the West to deep-sea ports, mining and container shipping in the East and South East, the potential in the world’s fourth biggest island has recently been identified by Chinese investment, which has pledged $2.7 billion to projects that range from shipyards and fisheries to aquaculture.

The latter industry is of particular interest to many investors and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) as it’s a way to work with coastal communities to develop sustainable sources of income.

A good example of this is the seemingly humble sea cucumber which is found in abundance in the waters around Madagascar and has a market value of around €860 a kilogram, particularly in China where it is seen as a delicacy when processed and dried.

With the help of British NGO Blue Ventures, 700 local people have been trained to work as sea cucumber farmers in the waters around the island’s Bay of Assassins. Thousands have been bred, farmed and sold, which has not only allowed locals to raise their standard of living, but also ease the pressure on other marine species and increase the island’s blue-economic growth further.

-

Somalia

“Somalia potentially stands to gain the most from a robust and sustainable blue economy,” President Mohamed Abdullahi Farmajo claimed last year.

The president’s positive forecast is surely based on the fact that Somalia boasts approximately 3,000 kilometres of coastline and an ocean territory that stretches around 120 kilometres off shore.

Thanks to monsoon winds which enrich Somali waters with nutrients and food, the country’s ocean resource is bountiful. However, the threat of piracy has curtailed a booming ocean economy as many foreign vessels, from industrial longliners to rillnetters, have been forced to avoid Somali waters.

But an increased international naval response and presence off the Horn of Africa means Somalia’s fisheries-based economy is on the increase and proving to be one of the country’s most prominent blue-economic resources.

And there appears to be plenty of room for sustainable growth, according to the One Earth Future Stable Seas Maritime Security Index, as long as the focus switches from top-of-the-food-chain fish, such as sharks, tuna and marlin, and concentrates on the smaller pelagic fish, like the Indian oil sardine.

The index predicts these shoals could be harvested at four times the current rate. This is backed up by the Secure Fisheries’ report Securing Somali Fisheries, which says there are plenty of opportunities to take advantage of the export market for these fish species.

Crucially for the country, the Maritime Security Index also reveals that Somalia is in a very strong position when it comes to sustainability and resilience to climate change, which means the country is free to invest in its ocean economy without having to worry about first undoing the damage caused by years of overfishing.

-

Kenya

Somalia’s southerly neighbour has a blue economy that currently contributes only 2.5 per cent to its GDP, but there are untapped resources in the country’s expansive 200,000-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

Kenya lies within the lucrative tuna belt and it’s estimated that there are between 150,000 and 300,000 tonnes of fish swimming throughout the EEZ, which is why one of the most pressing blue-economy principles of the Kenyan government is increased investment in the sustainable development of its tuna resources.

Encouraging Kenyans to eat more fish is also vital for food security and a healthy ocean economy as currently the average Kenyan eats just 4.6 kilograms of fish a year, well below the African average of 10 kilos annually. However, with a concerted effort concentrating on availability and education, it is hoped the country could boost this average well beyond current consumption and compete with the global average of 20 kilos a year.

In addition, Kenya has the option to look inland to blue-forest habitats, such as mangrove forests, where carbon is stored and there is a unique financial gain to be had as blue-carbon markets offer economic incentives to manage these resources sustainably. The Blue Carbon Project in the southern part of Gazi Bay is expected to generate up to 3,000 tons of CO2, which would inject almost $12,000 a year into the local community in the form of carbon credits sold on the voluntary carbon market.

-

South Africa

Phakisa means hurry up in Sesotho, one of the official languages of South Africa, so it’s no surprise that the strategy put in place by the South African government to grow a sustainable blue economy is called Operation Phakisa.

The initiative is targeting four key areas of blue-economic growth: marine transport and manufacturing; aquaculture; offshore oil and gas; and, ultimately, marine protection. The government estimates the oceans bordering South Africa on three sides, giving it a coastline almost 4,000 kilometres long, have the potential to add R177 billion (£9.6 billion) to GDP and create more than one million jobs by 2033.

These ocean economy estimates are primarily predicated on the growth of domestic shipping, as the country sits on one of the busiest trade routes in the world. However, from the approximately 13,000 trade cargo ships that visit South African ports every year to deliver imports and export local produce and minerals, only a handful are registered under the South African flag.

This means the local economy isn’t benefiting from the healthy and profitable shipping industry right on its doorstep, which is why moves are being made to grow the country’s domestic ship registry. But the number of South African-flagged ships is only expected to reach half a dozen by the end of the year.

However, this will have some knock-on effects on maritime employment. Most notably it will enable South African-born seafarers to complete the cadetship berths they need to receive their qualifications and start benefiting from the ocean economy. Operation Phakisa is also providing training for these ratings and officers that will see the number of South African-born seafarers swell to 12,000 by the end of the year.

-

Nigeria

Of the blue-economy sectors available to the Nigerian government, including aquaculture, deep-sea development and seafarer training, it is perhaps shipbuilding and repair yards that have the potential to provide employment for millions, as well as food security and GDP growth.

Lack of investment in shipbuilding and repairs has forced Nigerian maritime operations to look elsewhere for these services, and the country’s blue economy has been haemorrhaging capital and lost labour potential to foreign nations for years.

Developing new infrastructure like this, as well as investment in deep-sea ports and intermodal transport, has become one of the most pressing blue-economy principles of the federal government in an attempt to drive growth in the ocean economy.

However, there is a booming demand in Asia for the scrap metal that shipwrecks provide and recovered vessels are fetching healthy sums on the international market. A concerted marine salvage programme would not only begin to provide fresh revenue, but would also kickstart the process of cleaning up the coastline.

More capital is being lost because foreign carriers, who are benefiting from Nigerian oil production – Nigeria is the world’s 16th-largest oil producer – dominate the country’s shipping industry. This is why government programmes are underway to establish a national carrier, funded by the private sector, which will ensure oil export revenues stay in the country and are not lost with every foreign ship that leaves a Nigerian port.

Madagascar

Somalia