China may be the world’s second largest economy, trailing the United States, but it’s by far the globe’s biggest manufacturer of every type of product you could imagine from artificial Christmas trees to shoes or solar cells.

Take more than 500 types of industrial product and China ranks first for 220 of them, globally. Yet Beijing isn’t satisfied with just being the world’s factory for cheap goods.

More than a third of the country’s 800-million workforce produce biblical amounts of stuff, generating $3 trillion annually, but China’s position is slipping. It’s political and economic leaders know the country can’t rest on its laurels for long. There are more than a few rivals nipping at its heels, but it has a plan.

On one side, there’s increasing competition from developing countries. China’s wages are on the rise, especially on its eastern seaboard, its workforce is ageing and there’s an oversupply of some goods. At the same time, the five Asian nations of Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, India and Indonesia, known as the Mighty Five, are starting to look like a new China in terms of low-cost labour, favourable demographics, market growth and agile manufacturing capabilities.

It’s a warning sign that the country’s manufacturing industry needs a makeover

On the other, more advanced countries have either moved production back home or are outpacing China when it comes to high-end manufacture, innovation and technology. For instance, the US is expected to overtake the Asian giant and assume the number-one position in the Global Manufacturing Competitiveness Index in the next three years.

“Germany also averages more than 300 industrial robots per 10,000 industry employees, China only averages 19. China’s manufacturing industry needs a push to take it to the next level and avoid being squeezed,” says Ricky Tung, China industrial products and services leader at Deloitte.

China’s leaders lament how its manufacturers are heavily reliant on core components developed by Western corporations and that so much of the added value for iPhones, laptops and other devices resides overseas, while the low-grade assembly goes on in Guangdong or Sichuan. US President Donald Trump hasn’t helped by threatening tariffs on imported Chinese goods and pestering companies such as Apple to stop making products in China.

Rising costs are also reducing manufacturers’ profits, causing capital to flow out of China’s real economy and into the property market. Its evolving middle class don’t want to sweat it out on low-grade production lines. It’s a warning sign that the country’s manufacturing industry needs a makeover.

“Economies that change and move up the value chain have delivered better working and living standards across the world since the industrial revolution,” says David Martin, director of the China-Britain Business Council.

The plan

Therefore, Beijing has hatched a plan. It’s banking on an industrial blueprint called Made in China 2025 (MIC2025), inspired by Germany’s Industry 4.0 and the United States’ Industrial Internet of Things, to breathe new life into the sector. It aims to shift China towards higher value, advanced manufacturing dominated by automation, robotics, big data and cloud computing. The key aim is to boost productivity.

This plan has even greater impetus as China now hits the middle-income trap, with GDP per capita at roughly $8,000 a year. This term refers to countries who find it difficult to catch up with high-income economies as wages rise and they lose their competitive edge exporting manufactured goods. There’s a belief that new technology invested into warehouses from Chongqing to Tianjin could give China the shot in the arm it needs.

“Traditional drivers of growth such as investment in infrastructure are losing steam. China has to go for a new growth model driven by innovation,” says Jost Wübbeke, head of program economy at the Mercator Institute for China Studies.

“China’s challenge is to incentivise an industry that’s used to low-end manufacturing. It now needs to design and produce cutting-edge tech. It will also need to upgrade facilities by using advanced production technology, especially smart manufacturing tools and processes.”

The goal of MIC2025 is to boost ten industrial sectors from aerospace to electric vehicles, robotics to medical equipment. It sets out growth targets, research and development priorities and China’s future global market share. This scheme from Beijing’s ruling elite is both prescriptive and specific in the targets it sets.

There are new opportunities for UK expertise to partner with China

The Made in China concept is not just about branding the country, but about giving its people the toolset and the capabilities so it can thrive in certain sectors. For instance, MIC2025 expects Chinese suppliers of high-tech to reach a domestic market share of 70 per cent within the next eight years.

“The fact that China is attempting to move its manufacturing up the value chain is inevitable; its near neighbours have developed in a similar path,” says Mr Martin. “MIC2025 is important in terms of changing the competitive environment and the challenges of doing business with the country. There are also new opportunities for UK expertise to partner with China.”

Whether state-driven policy can dictate innovation, which is usually a bottom-up, organic process, remains to be seen. However, the country is in a unique position. Already three out of the top five smartphone makers globally are now Chinese corporations in terms of the volume of shipments, according to the International Data Corporation.

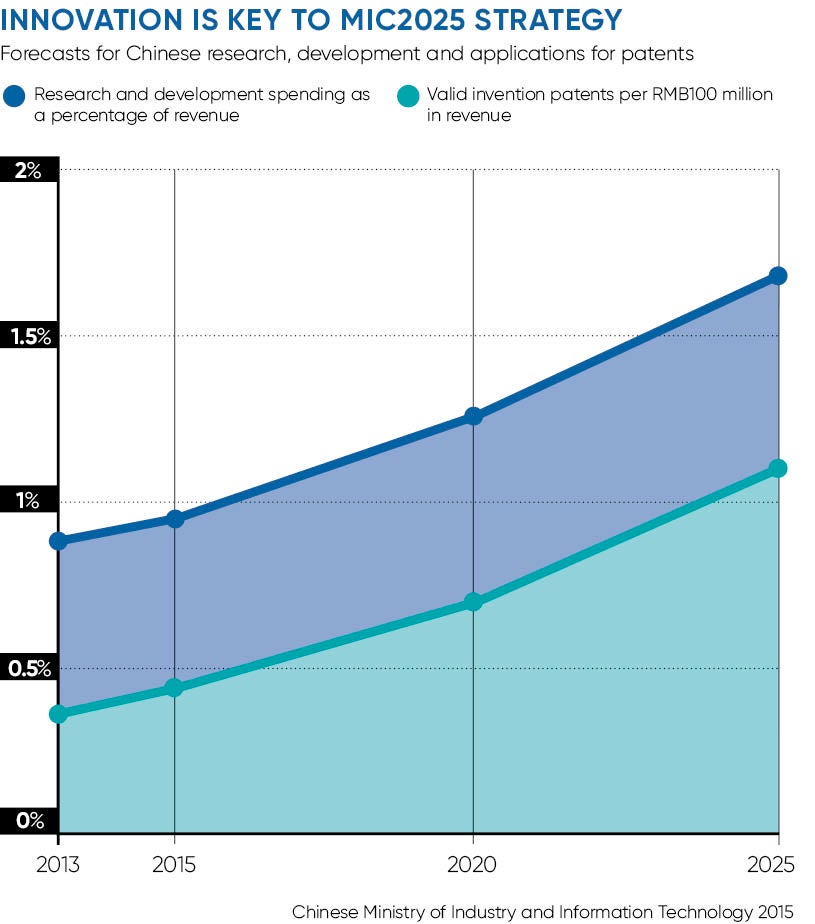

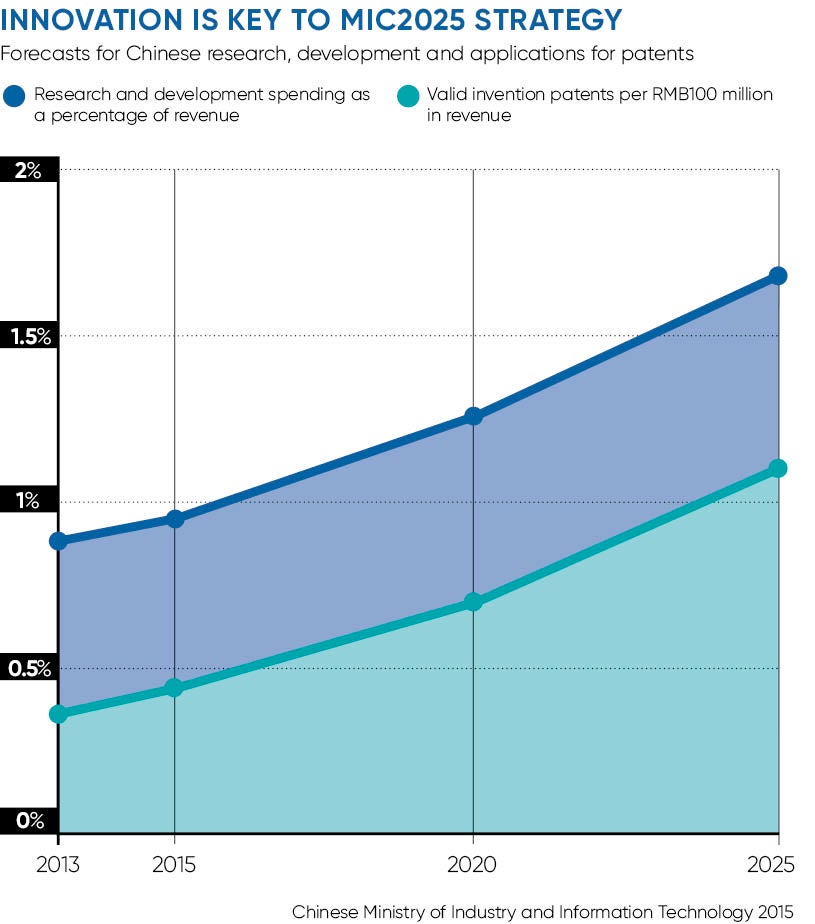

China has also broken the patent application record, with more than a million domestic submissions, according to the World Intellectual Property Organisation, more than the US, Japan and South Korea combined.

One option could be for China to continue to buy up know-how overseas. For example, mainland enterprises have already gobbled up Bio Products Laboratory in the UK for $1 billion, London’s Black Cabs and Weetabix.

“China is relatively cash rich, therefore looking at international companies with an eye for mergers and acquisitions is the quicker route to moving up the value chain and to leveraging both the skills and brand reputation of the international company,” says Mr Martin.

This could also help address the technology gap. Chinese manufacturers still lag behind many leading enterprises from across the globe. Take high-performance six-axis and welding robots; they must still be imported to work on China’s shopfloors, as are many other core components for industrial robots.

“Foreign brands represent nearly 70 per cent of the market share of the Chinese robotics market,” says Mr Tung. “There is also a lack of talent. This makes it very difficult for many Chinese enterprises to install and use high-end manufacturing technologies.”

That’s because complex IT processes and computerised machines require detailed expertise in various fields of automation, engineering and software. There is still a question whether the labour force in China can reskill itself. Herein lie many opportunities for overseas corporations.

Another issue that’s not been fully addressed is that increased productivity and automation in China’s manufacturing industry as MIC2025 takes hold could mean fewer jobs on the shopfloor. However, a record-breaking eight million students will graduate from Chinese universities this year, twice as many as graduate in the US, and there’s also been an explosion in engineering graduates.

“The potential loss of workforce due to automation is not yet a major issue for the [Chinese] government. However, sooner or later, China will have to face this challenge,” says Mr Wübbeke. “The future of work is not only a Chinese issue. Digital transformation, changing social values and worker expectations will be disruptive in China and globally.”

What is certain is that the world will see more Chinese corporations entering and shaping global markets. There’s no doubt that the Made in China label still has as a firm future.

The plan