As it stands, buyers of new hybrid and electric cars in America can claim back a federal tax credit of up to $7,500 on their purchase. The offer is an Obama-era initiative, which was designed to get more environmentally-friendly vehicles on the road and stimulate the US car manufacturing economy.

But at a November 2018 press conference, National Economic Council director Larry Kudlow said President Trump planned to end the incentive “in the near future”. When pressed, he was reported to have mooted a 2020 or 2021 cut-off.

If the US wants to be manufacturing cars in 20 years, we need to get in front of electric technology

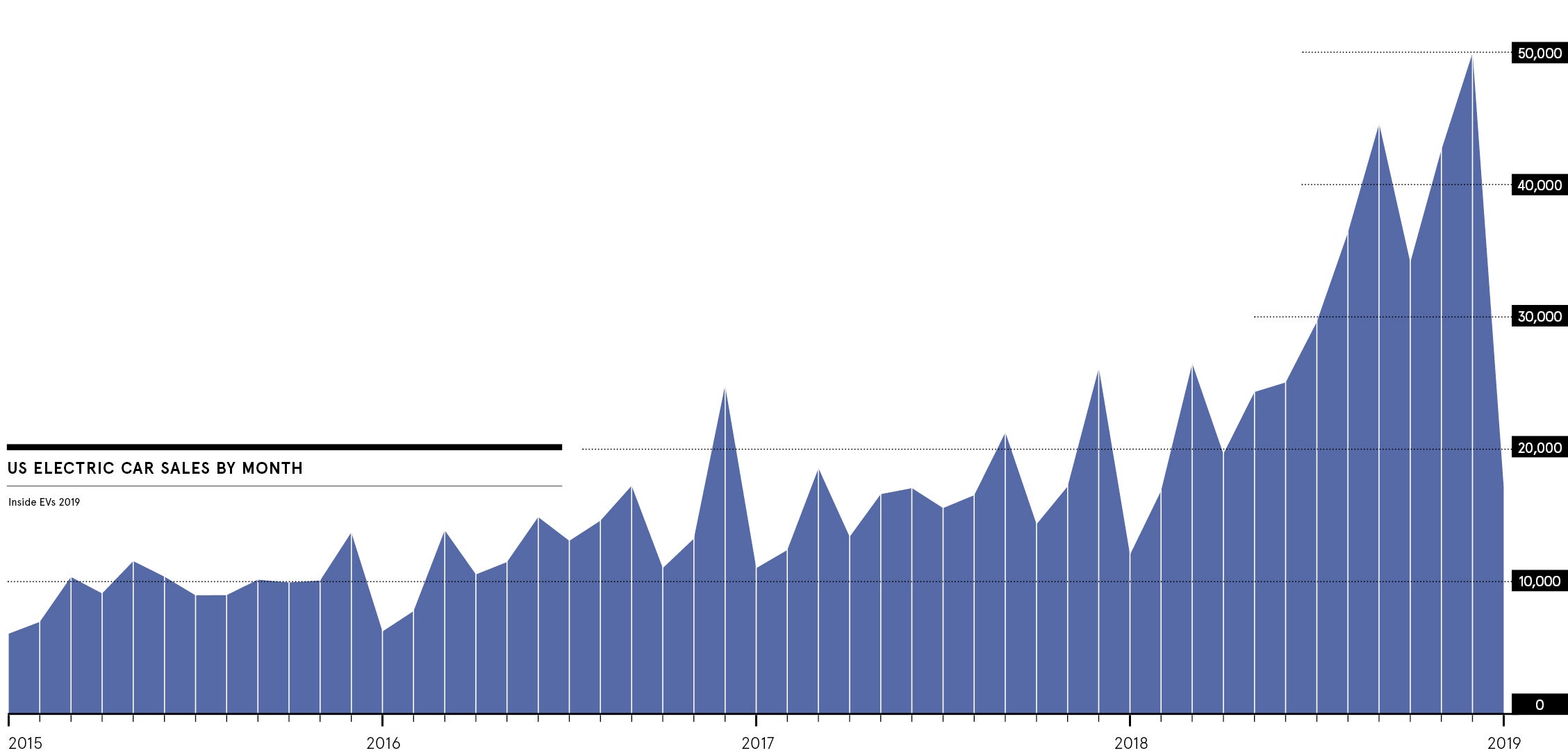

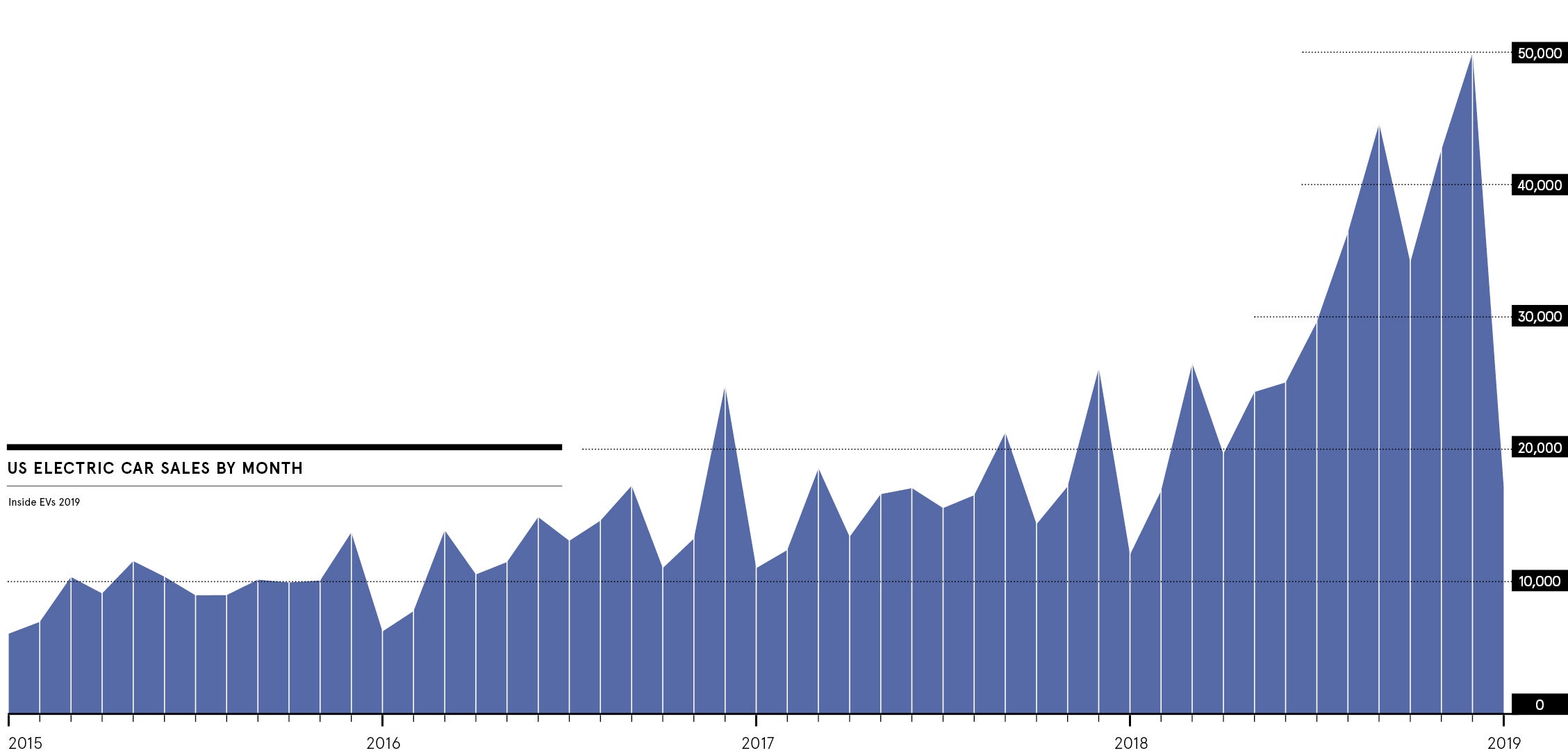

Currently, a maximum of 200,000 electric cars per manufacturer qualify for the deal. Tesla was the first to hit the cap in the autumn of 2018 and General Motors followed soon after in December 2018. Other manufacturers with electric vehicle (EV) offerings, including Nissan, Ford, BMW and Toyota, are thought to have tens of thousands of cars still to sell before they hit 200,000 units.

Will electric car manufacturers suffer without the levy?

Without the bait of a generous tax rebate to offer potential electric car converts, do these manufacturers stand to lose a lot of business in the coming years? Joel Levin, executive director of California-based EV advocacy group Plug-In America, says the future is uncertain. He is sceptical whether a ban on the tax credit could be enacted in the timeframe Mr Kudlow has indicated, if at all.

Mr Levin concedes that anti-subsidy sentiment is strong in some quarters on Capitol Hill. “There are a few members of Congress who would like to kill the tax credit right now. But I think that’s very unlikely,” he says, because axing the credit would probably require an Act of Congress to remove or amend existing law.

At the same time as the largely Republican-backed desire to end the tax credit, there is a Democrat-led movement to extend it to 2028. “That actually has a lot of interest in Congress. There’s a lot of political support for it,” says Mr Levin. Yet steering more electric cars on to America’s roads requires more than convincing lawmakers in the corridors of power. Getting the country’s voters of all persuasions on side will be just as important to future sales growth.

Without electric cars, US car manufacturing won’t survive

Making the business case for electric cars to consumers is key. Mr Levin says: “If the US wants to be manufacturing cars in 20 years, we need to get in front of electric technology. Otherwise, cars are going to be built in Germany and China because they’re both making vast, vast investments in EV. If we don’t, we’ll be buying our cars from them. When we talk to people from the Midwest – Ohio, Michigan – states, where there’s a lot of auto manufacturing, our argument is that this is the technology of the future for cars. No one really disputes that at this point.”

Even if the tax credits are cancelled, he points out that for the majority of the US EV market’s clientele, $7,500 represents small change. The most popular brand, Tesla, sells cars which are largely the preserve of the wealthy. The most basic model starts at around $35,000, but most cost upwards of $100,000.

Mr Levin says for consumers able to part with this kind of cash, “a $7,500 tax credit is nice to have, but it’s probably not going to be a core part of your decision”. Instead, a tax credit cull would have a greater impact on sales of the cheaper vehicles, hitting drivers on lower incomes. He says: “Look at Nissan’s Leaf EV model, which retails at about $30,000; if you can chop $7,500 off that price using a tax credit, that will make a big difference to your customer.”

Abolishing the levy will slow the market, not stop it

If the tax credit is axed, Mr Levin says: “It would hurt the industry, but I don’t think it would kill the US EV market; it would slow it down.”

Tom Wood, chief executive of used-vehicle database Cazana, says if the credit is cancelled, it could have the effect on ramping up sales of second-hand electric cars. This is a trend which is already playing out in the UK. Grants for buying a hybrid or all-electric vehicle were slashed in the UK last October and since then “the secondary car market is showing a rise in the pricing of plug-in hybrid vehicles”, he says.

As EV technology prices fall and uptake rises, Mr Wood believes the greater challenge lies in making sure the battery charging infrastructure is in place to support market growth. “I think tax credits are getting less important,” he says. “It’s a nice marketing thing to be able to use, but the economics of electric cars is stacking up on its own now. The problem in the US is that it is a big country and people drive long distances. That’s what the automotive industry now needs to crack: the infrastructure.”

Will electric car manufacturers suffer without the levy?

Without electric cars, US car manufacturing won't survive