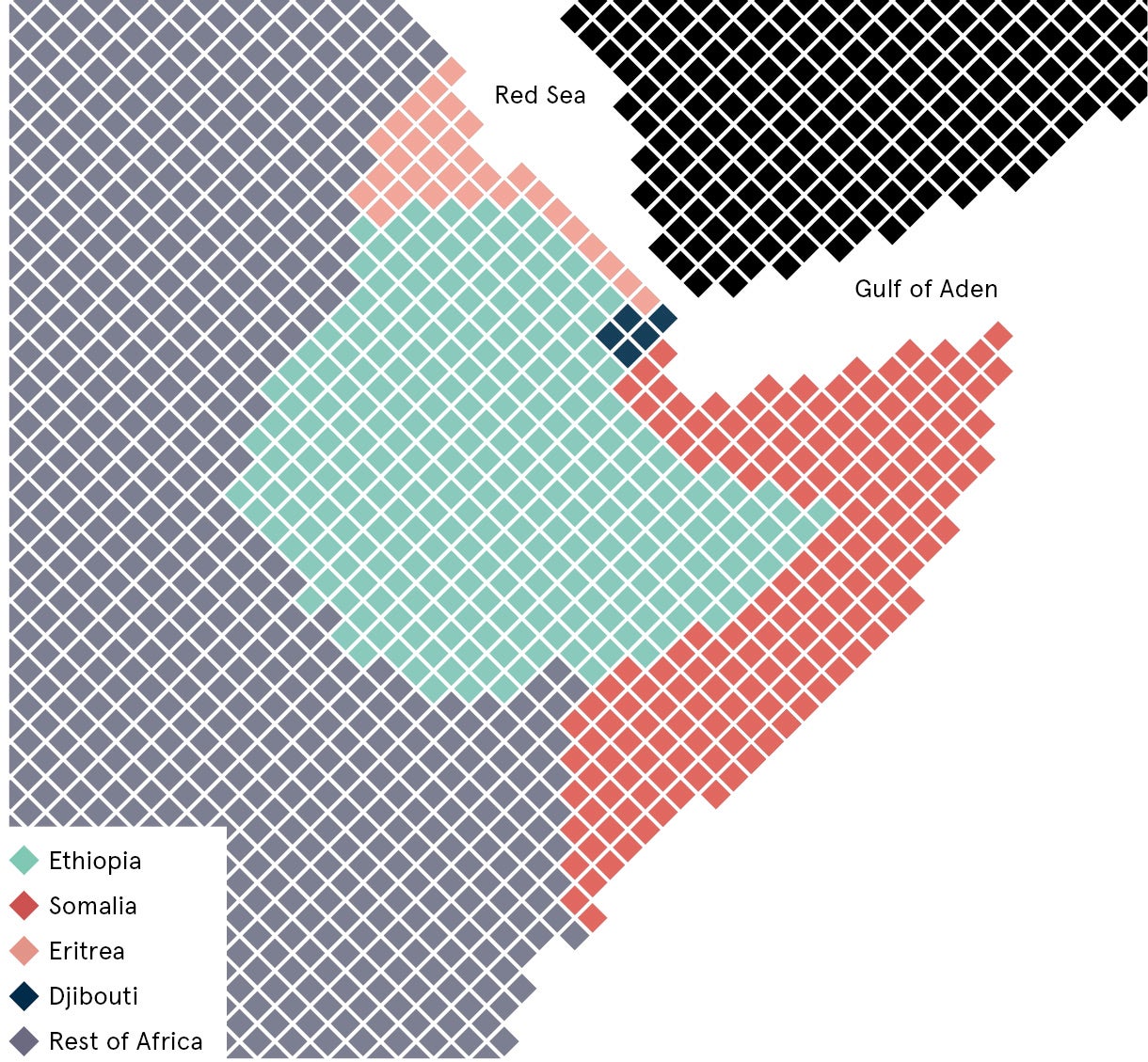

For decades it has been one of the world’s most fragile regions, plagued by armed conflict, poverty and periodic droughts. But in the 1990s, the Horn of Africa, comprising the states of Somalia, Eritrea, Ethiopia and Djibouti, became the focus of a somewhat surprising investor: DP World, a global port operator that is majority owned by the government of Dubai, part of the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

We are seeing a race between regional and global players to take advantage of big opportunities located in the region

From its headquarters in Dubai’s sprawling port of Jebel Ali, the maritime company and its Emirati owners saw in the Horn of Africa what many others didn’t: an area of vast economic potential and geostrategic importance.

In 2006, DP World won a contract to build the Doraleh container terminal in Djibouti, now the small nation’s biggest employer and source of revenue. Years later, in 2016, it signed a $442-million agreement with Somalia’s secessionist region of Somaliland, to manage and invest in the deep-sea port of Berbera. Both decisions proved prescient.

Middle-Eastern countries battle for space in the Horn of Africa

Today, the UAE is among a number of Gulf and Middle-Eastern countries scrambling for control of ports across the Horn of Africa, in a race that analysts say could benefit, but also potentially destabilise, the already fragile east-African region.

In recent years, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have become active in ports and military bases in Djibouti, Eritrea and Somalia, while Qatar and Turkey, who align with Saudi Arabia’s regional rival Iran, are building in the Somali capital, Mogadishu, and the Red Sea port of Suakin, off the coast of Sudan.

“We are seeing a race between regional and global players to take advantage of big opportunities located in the region,” says Camille Lons, programme co-ordinator at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

One reason for this scramble is commercial. The Horn of Africa is strategically located next to one of the world’s busiest sea lanes, with access to both the Red Sea and Indian Ocean. Every day around five million barrels of crude and petroleum products flow through the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, a neck of water bordered by Eritrea and Djibouti.

“It is one of most trafficked shipping lanes in the world,” says Olivier Milland, a political risk analyst at Allan & Associates.

Political rivalry meets commercial interest

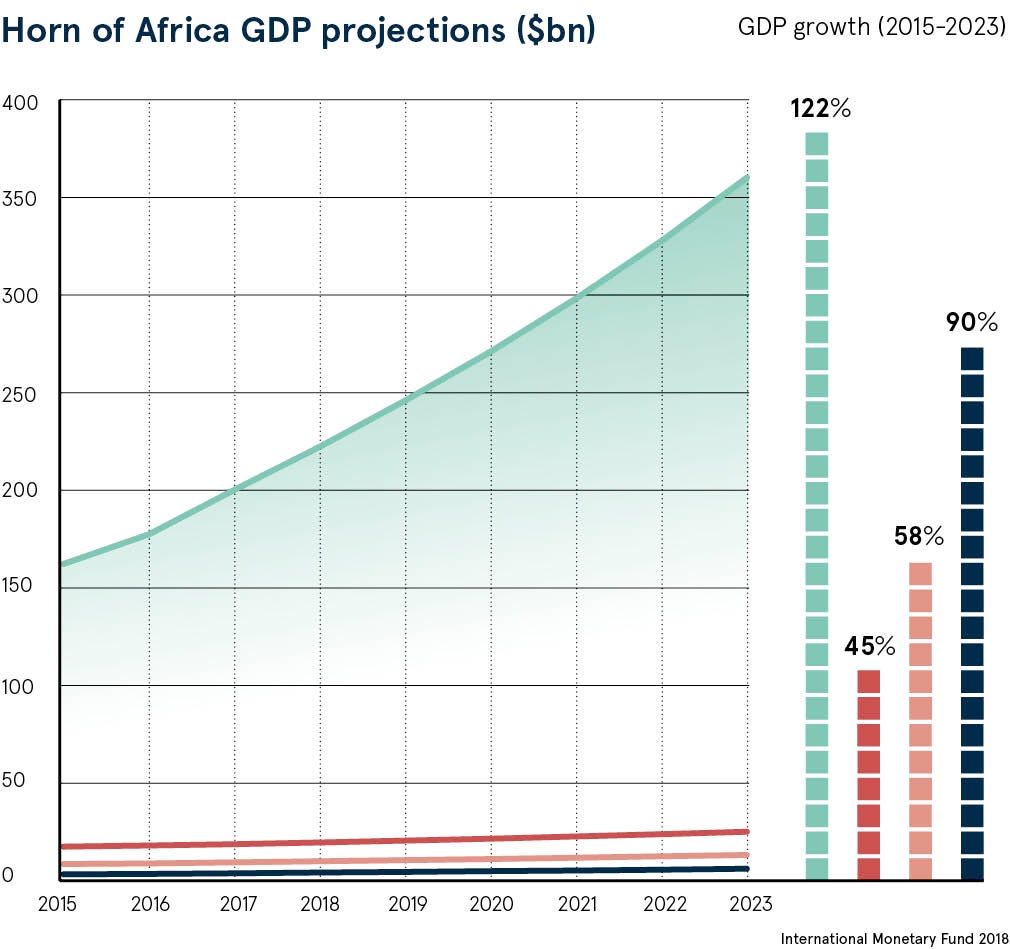

More ports and better infrastructure are also needed to handle growth in the Horn of Africa’s largest economy, Ethiopia, which is predicted to expand by 8.5 per cent this year, but is landlocked and therefore heavily dependent on Djibouti.

Since sweeping to power in April, Ethiopia’s new, reform-minded prime minister Abiy Ahmed, 42, has made port development a key priority, calling for investments across the region.

“It is very important for Ethiopia to diversify its trading streams,” says Mr Milland.

But Gulf interest in the Horn of Africa is also being driven by regional political rivalries, with different states seeking to secure strategic locations, especially in the context of the war in Yemen, where a military coalition led by Saudi Arabia and the UAE has been fighting Iranian-backed Houthi rebels since March 2015.

The UAE has been launching operations in Yemen from a military base around the Eritrean port of Assab and also has armed forces present in Berbera, a port in Somaliland.

Will tensions spill over to conflict in the Horn of Africa?

As geopolitical interest in the Horn increases, observers fear these regional Gulf rivalries could end up spilling over.

This was the case after the Gulf crisis of June 2017, when Saudi Arabia and its allies severed diplomatic ties with Qatar, which they accuse of supporting Iran, the Muslim Brotherhood and a form of political Islam which threatens the stability of their regimes.

During the crisis, the governments of Djibouti and Eritrea sided with Saudi Arabia and the UAE, causing Qatar to withdraw peacekeepers from a disputed border between the two Horn of Africa countries, where they had been patrolling since 2010.

Somalia’s breakaway region of Somaliland, which is not internationally recognised as an independent country, also chose the side of Saudi Arabia and the UAE, while the central government in Mogadishu, which is closer to Qatar and Turkey, stayed neutral.

Analysts say this has amplified dangerous divisions between Somalia and its regions, a divide that can be seen most clearly in Berbera, an ancient port town in Somaliland.

UAE and Somali rivalries meet and merge

Last year the UAE began constructing a military base in Berbera, which is 190km south of Yemen. In March this year, DP World also finalised a contract with the Somaliland authorities to develop and operate Berbera’s port, in which Ethiopia also has a 19 per cent stake.

The venture has the potential to turn Somaliland into a regional maritime hub, but has prompted a furious response from Somalia’s federal government which regards the region as part of its territory and says the secessionists have no right to sign international agreements.

“The deal has been perceived as a foreign intrusion by Mogadishu,” says Ms Lons.

On March 12, Somalia’s federal parliament took the step of banning DP World from operating in the country in a move Somaliland’s president Muse Bihi Abdi referred to as a declaration of war.

The crisis has since soured relations between Mogadishu and the UAE. In April, Somali security forces confiscated millions of “undeclared” US dollars from a UAE plane landing in the capital. The UAE responded by ending a military training programme it was running in Somalia.

Maritime agreements playing newly strategic role on global stage

Despite its long-standing involvement in the region, the UAE has also run into problems in Djibouti. In February, following years of dispute, the Djibouti government dramatically seized control of the DP World-operated and part-owned Doraleh Container Terminal.

The Djibouti government accused the company of poor performance and failing to expand the terminal as quickly as it had promised. It also claimed the company paid bribes to secure the original concession, a claim rejected by the London Court of International Arbitration.

You have the largest Middle-Eastern maritime logistics shipper DP World in an implicit, forward-looking contest with another global shipping alliance, which includes the Chinese - David Styan, Lecturer in politics, Birkbeck, University of London

With the UAE sidelined in Djibouti, analysts say other countries could step in and that Gulf nations aren’t the only ones in the running. Some have speculated that the Djibouti government may hand over Doraleh to investors from China, which is currently building a naval base in the country.

The involvement of China in the Horn of Africa’s ports adds “another dimension to an already complicated equation”, says David Styan a lecturer in politics at Birkbeck, University of London.

“You have the largest Middle-Eastern maritime logistics shipper DP World in an implicit, forward-looking contest with another global shipping alliance, which includes the Chinese,” Dr Styan adds.

But as different nations scramble for control of ports in the Horn of Africa, Mr Milland says it is worth remembering that the region is still prone to instability. Somalia is dealing with the threat of resilient al-Shabaab militants, Eritrea remains one of the world’s most repressive countries, and even Ethiopia, considered relatively stable, is currently facing widespread ethnic violence and displacement.

“The area has huge commercial potential,” Mr Milland concludes, “but there are still regional and country tensions that could put new investments at real risk.”

Middle-Eastern countries battle for space in the Horn of Africa