Today’s largest manufacturing country headed the output league table nearly two centuries ago before being ousted by Britain in the first industrial revolution.

China accounts for 20 per cent of global output, followed by the United States with 18 per cent, Japan 10 per cent, Germany 7 per cent and South Korea with 4 per cent, according to the most recent (2015) data from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. The UK is ninth with 2 per cent.

In the intervening centuries there have been sizeable shifts. China reclaimed its crown after 150 years by overtaking America during the past decade. Although it is early to make firm predictions about who might be winners and losers in the fourth industrial revolution, all will be trying to learn from

past experience.

The impact of a fourth industrial revolution will depend on geopolitics. A current backlash against globalisation threatens to limit the spread of benefits via trade

Britain took the lead during the first industrial revolution

China was a leader in many areas of industry for hundreds of years, responsible for technological breakthroughs including paper, clocks and cannon. Then Britain began to overhaul it with an explosion of innovations such as steam power and the factory system in the first industrial revolution from about 1760 to 1840, which simultaneously saw populations and living standards eventually rise.

Britain did not overtake China’s output until 1860, according to calculations by economic historian Paul Bairoch. Then Britain’s reign as top manufacturing nation lasted less than 40 years. By 1900 the US had overtaken it, with Germany rising fast too, during the second industrial revolution of 1870 to 1914, which saw widespread adoption of technologies such the telegraph, railways and electricity.

The third industrial revolution, from the 1950s to the present day, has been a digital age that includes personal computers, mobile phones and the internet, with industrial applications in areas such as robotics.

A nascent fourth revolution, which some see as a continuation of the third, includes technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), 5G telecoms, collaborative robots or co-bots, the internet of things, quantum computing, nanotechnology, biotechnology and 3D printing. What distinguishes it is a mingling of the physical, digital and biological spheres, referred to as cyber-physical systems.

The US has been the winner of the third industrial revolution

“For a lot of these technologies, we are still in the hype stage and some of the consequences in the longer term will take us by surprise when they finally happen,” says Diane Coyle, professor of public policy at the University of Cambridge.

Being first adopter of a technology does not necessarily guarantee competitive advantage, she adds, as sometimes a second adopter can capitalise on the first’s mistakes. “It also depends on the economic context. Incentives have to be in place for technologies to be used,” says Professor Coyle. Winners are likely to be those who make best use of technology, not necessarily those who invent it.

In the third revolution, the US has been the technology leader, with companies such as International Business Machines (IBM), Microsoft and Apple. But its share of global manufacturing shrank as production was offshored to cheaper locations. China and emerging economies benefited from a liberal trading regime coupled with new communications technologies.

Some see China’s further advance as likely, given the effort it is making to achieve leadership in technologies of the next generation of commerce and military equipment such as AI, robotics and gene-editing, a strategic concern for the US, which lies behind recent trade tensions.

On the other hand, developments such as 3D printing offer a chance for Western nations to bring some manufacturing home. There has been some reshoring already, though not enough to shift the overall balance.

Adoption of fourth industrial revolution tech is sluggish

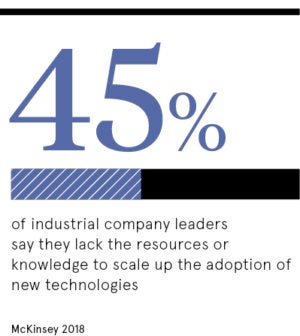

Adoption of fourth industrial revolution technologies globally has been “slow and limited across all industry sectors”, according to management consultants McKinsey: “More than 70 per cent of industrial companies are still either at the start of the journey or unable to go beyond the pilot stage.” A PwC study found that just 5 per cent of manufacturers in Europe, the Middle East and Africa are “digital champions”, compared with 11 per cent in the Americas and 19 per cent in the Asia-Pacific region.

Some companies are put off not only by the cost of investment, but by the need to reshape their organisation to benefit from it. Productivity gains in recent years have been slow. Economists such as Robert Gordon argue that innovations are less transformative than those in earlier periods, such as electrical power and powered flight.

Countries can help their case, however. Many have strategies aimed at the fourth industrial revolution, such as Germany’s Industrie 4.0, the UK’s Industrial Strategy, Made in China 2025 and Japan’s Society 5.0. Typically, efforts include steps such as building awareness, financial incentives, improving the legal framework and education programmes.

Geoff Mulgan, chief executive of Nesta, an innovation charity, points out that technologies such as driverless cars and drones are “very systemic in nature”, so they require government action on regulation and infrastructure as well as adoption by companies.

Geopolitics will decide the winner of the fourth industrial revolution

Also, the technologies question traditional concepts of manufacturing, for example people in future may buy mobility rather than cars, which requires a different type of service. “At the moment, most countries that are good at manufacturing are not so good at this,” he says.

Mr Mulgan advocates “anticipatory regulation” such as test beds in which innovations are developed in discussion with regulators, who can remove barriers or pre-empt threats that might lead to a public backlash. The UK, for example, has a £10-million Regulators’ Pioneer Fund. Similar approaches are being tried in Singapore, Canada, United Arab Emirates and Finland.

The impact of a fourth industrial revolution will depend on geopolitics. A current backlash against globalisation threatens to limit the spread of benefits via trade.

“It makes it hard to see macroeconomic conditions that mean markets are growing and there is going to be demand for new technologies,” says Professor Coyle. She is “long-term optimistic” about technology-led growth, “but short-term pessimistic because political and

social adjustments are always going to be challenging”.