When the face of chancellor Rishi Sunak is plastered all over the media, workers and businesses across the UK know the Treasury’s magic money tree is being shaken again. First it was the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme, then the Job Support Scheme and most recently its expansion in the wake of forced local lockdowns.

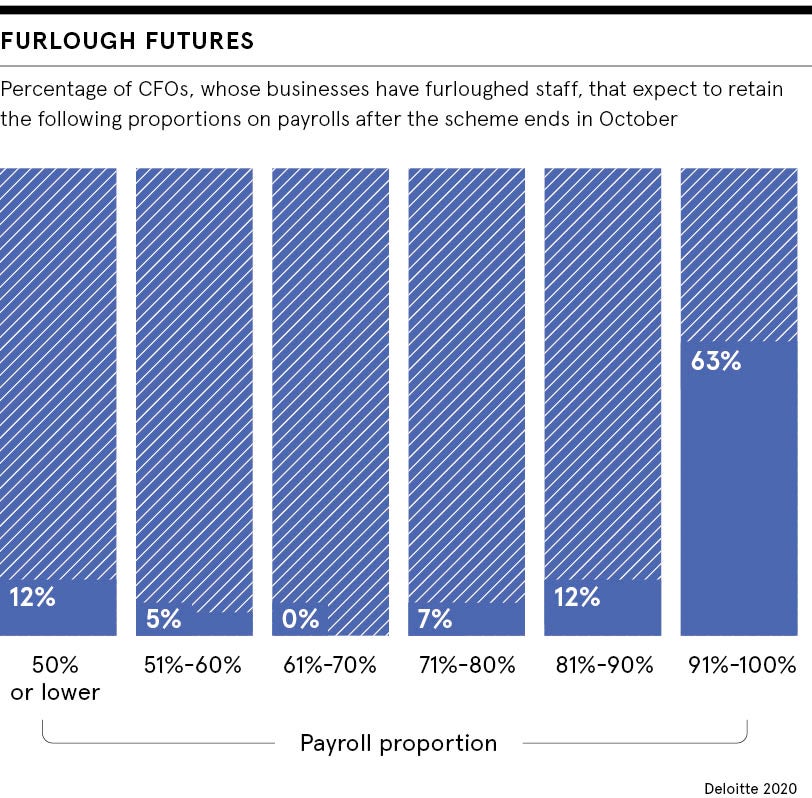

The economy-wide furlough scheme has cost an estimated £50 billion to date and has been an extraordinary intervention in the job market. Yet government support that paid up to 80 per cent of staff wages stops at the end of October. Beyond this, employers will have to shoulder a much higher share of the labour bill, if they want to keep staff on their books.

Incentivising employers to keep staff on

“The Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme was designed earlier in the year when there was talk of a V-shaped economic recovery and everyone thought it would be over by Christmas. The priority then was to keep the economy frozen so it could bounce back as quickly when the pandemic was over,” explains Xiaowei Xu, senior research economist at Institute for Fiscal Studies.

“Six months on, things are looking different. There has been a lot of talk about how the new Job Support Scheme, or JSS, does not incentivise employers to keep workers in jobs that don’t face demand right now, unless it would be more costly to replace them later. But this is not a design flaw, this is very much a design feature.”

Under the new scheme, starting in November for six months, the UK government’s contribution to pay packets falls sharply to 22 per cent, unless businesses are forced to shut by law due to COVID-19, then workers will get two thirds of their wages paid by the state. The chancellor has said the aim now is only to support viable jobs.

“The JSS assumes firms can afford to bear the cost of keeping workers on the payroll yet, with economic demand suppressed, the incentive for businesses to retain workers is reduced. With the existing system of ‘fire and rehire’, it’s likely firms will lay off workers rather than engage with the new scheme. There is now a real fear of rising unemployment,” says Professor David Spencer at Leeds University Business School.

The rise of the zombie economy

The Centre for Economics and Business Research has already raised its unemployment forecast, predicting 1.5 million more people could lose their jobs by Christmas, with the jobless rate climbing to 8.5 per cent. “We are currently in an unprecedented economic crisis; it’s hard to overstate the magnitude of the problem,” says Professor Michael Devereux, director of the Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation.

The ongoing pandemic is now driving structural change in the UK economy, with many firms waking up to the fact that a pre-COVID normal isn’t returning soon; think of those in the arts, hospitality or airline industries. Some jobs that were preserved by furlough are now obsolete. According to a think tank Onward, one in five UK businesses may well be “zombie companies”, marginally profitable firms incapable of dynamism or innovation.

We are currently in an unprecedented economic crisis; it’s hard to overstate the magnitude of the problem

“Supporting the illusion that everything is going to go back to normal fails to incentivise employers to make rapid decisions to restructure and delay necessary, as well as, painful adjustments until it’s too late to save a business. It makes workers less likely to agree to radical workplace changes in their existing employment or seek new jobs. By tying them to existing employment, the JSS may prevent workers from accessing retraining or moving to new sectors,” says Professor Len Shackleton, fellow at the Institute of Economic Affairs.

“The UK already has many zombie companies as a result of low interest rates, which are negative in real terms. Many will have fallen by the wayside during the pandemic, but this may have been offset by newly created zombie firms accessing government-backed loans and furloughing staff.”

Westminster must get serious about job creation

Earlier this year, the European Union proposed a “Marshall Plan” for economic reconstruction post-COVID, referring to the recovery led by America following the Second World War. The UK is going to need some similar policy grandstanding, as well as real action, if it’s not to be drowned by a tsunami of the jobless, as well as the media flotsam and jetsam, that’ll ensue.

“Westminster needs a plan for jobs, one that will facilitate a structural evolution, such as large-scale investments by the government in the public sector. There are real needs to be met in the economy and expansion of the public sector could help to create many socially useful jobs,” says Spencer at Leeds University Business School.

“There is also a need for bolder thinking around a Green New Deal and green technology investments. The government can borrow at low rates at the moment and could use public spending to pump-prime the economy, stimulating private sector jobs in the process.”

Making a path to a new job market

In many economic sectors, COVID-19 has been a catalyst for change, accelerating already existing trends by up to five years. The UK labour market is not immune to this, albeit stymied by furlough schemes.

“The trends which have been growing towards a totally flexible labour market, where individuals make themselves available for ‘gigs’ will be rapidly speeded up. As older workers retire or are forced out and a new generation enters the job market, they will demand work and pay, as well as flexible benefits that suit their lifestyles,” says Merrill April, partner at law firm at CM Murray.

“It is likely that some skilled workers will be lost, but they may exist in a ‘talent pool’ somewhere and be brought back although on much inferior terms or as self-employed freelance consultants.”

The United States, where firing and hiring is easy, has long supported unemployed workers through its benefit system. During the pandemic, the focus has been on generously giving money directly to workers instead of jobs tethered to firms. During COVID-19, this has allowed a much more flexible labour market to shift to where new demand has arisen, say from hospitality to online grocery deliveries.

“Enhanced redundancy packages, rather than continuing wage subsidy, makes better sense. Continuing support should be confined to a very narrow group of businesses where there is a strong expectation of future recovery, even in a world permanently changed by the pandemic,” says the Institute of Economic Affairs’ Shackleton.

“A fundamental shift to deregulation would help. There is no shortage of entrepreneurial talent in the UK, but we must ensure it is not helped by regulation designed for a different era. The focus has to be on jobs, jobs, jobs.”

When the face of chancellor Rishi Sunak is plastered all over the media, workers and businesses across the UK know the Treasury’s magic money tree is being shaken again. First it was the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme, then the Job Support Scheme and most recently its expansion in the wake of forced local lockdowns.

The economy-wide furlough scheme has cost an estimated £50 billion to date and has been an extraordinary intervention in the job market. Yet government support that paid up to 80 per cent of staff wages stops at the end of October. Beyond this, employers will have to shoulder a much higher share of the labour bill, if they want to keep staff on their books.