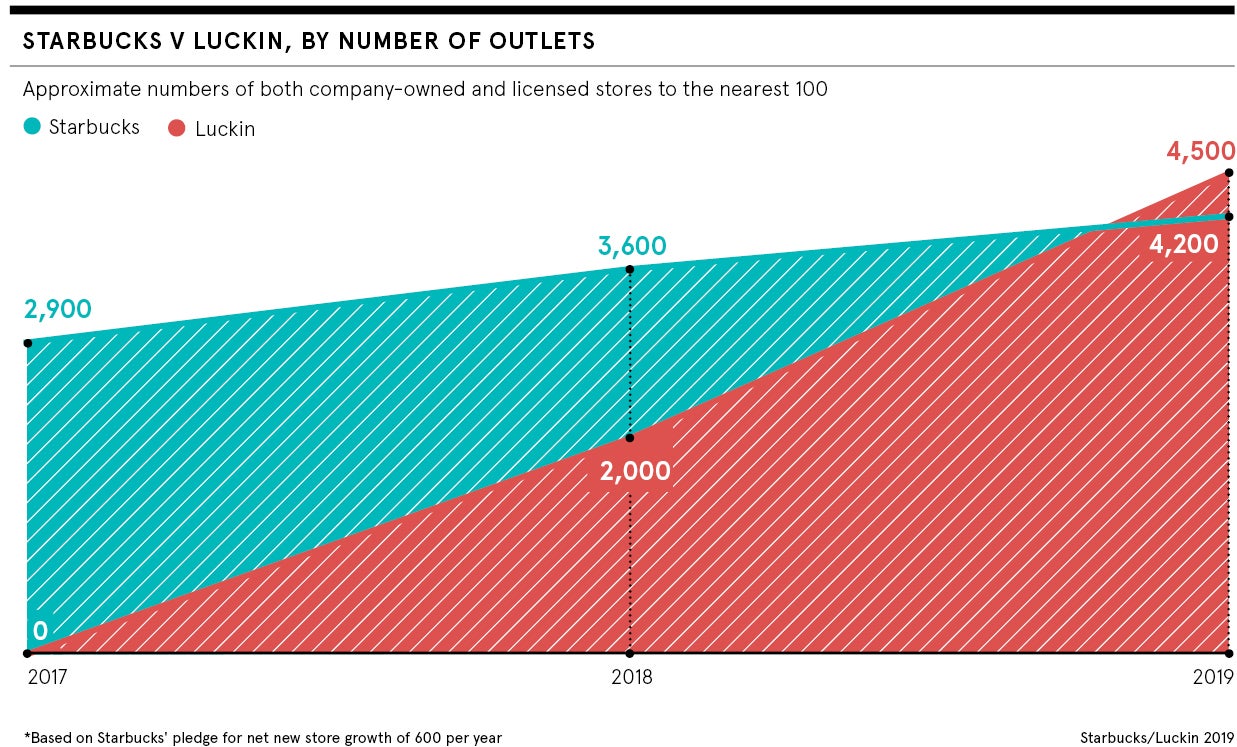

Chinese startup Luckin Coffee has a mission: “To defeat Starbucks in China,” according to chief operating officer Qian Zhiya. It’s already making good headway, last year opening its first 2,000 branches in China, while Starbucks has 3,600. The company has since announced plans to open a further 2,500 outlets in 2019.

Luckin’s success lies in its innovative business model; most of its branches are take-away only, reducing operational costs, and customers order via a dedicated app rather than visiting a store.

“Food and beverage is getting seriously disrupted by digital in China,” says Professor Jeffrey Towson of Peking University. “Delivery on demand is common.” But until last year, Starbucks didn’t offer delivery, which Professor Towson describes as “almost a crime in China”.

Luckin Coffee challenging with low prices, easy takeaway and bulk offers

Criminal or not, it meant Starbucks was missing out on a $37-billion take-away industry until last August when it partnered with the Chinese tech giant Alibaba to offer delivery. Luckin Coffee is also beating Starbucks on price. A latte from the American chain costs $4.28 compared with Luckin’s $3.54.

The sudden popularity of Luckin Coffee has won it a spot on the fast-growing list of Chinese unicorns; despite recording a loss of $116.34 million last year, it closed 2018 with a $200-million funding round that took its valuation to $2.2 billion.

According to chief marketing officer Yang Fei, the multi-million loss was in line with the company’s expansion goals. “What we want at the moment is scale and speed,” he says.

The real challenge for Starbucks and Luckin is not to steal customers from each other, but to expand the consumer base of coffee drinkers

Rebecca Zhang, 34, a travel agent in Beijing, orders Luckin Coffee on a weekly basis with her colleagues; the coffee company offers discounts for bulk orders, making it popular with office workers. For Ms Zhang, value is the main appeal. “The price is cheaper than Starbucks,” she says. “If the quality is fairly similar, why wouldn’t you choose something cheaper?” But she is also motivated by patriotism. “This is a local brand and we are supposed to support local brands,” she adds.

Starbucks may suffer from US-China trade war

Some analysts have speculated that Starbucks will be a victim of the fallout from the trade war between China and the United States. Chinese consumers have a history of boycotting foreign companies; in 2017, the South Korean conglomerate Lotte was forced to close nearly all its supermarkets in China after outrage at the installation of a US missile-defence system on Lotte-owned land in South Korea. Although aimed at North Korea, China believed the move made Chinese military secrets vulnerable.

Starbucks has so far escaped such a fall from grace, but ongoing tensions could jeopardise the American coffee chain’s second-biggest global market. Starbucks hopes to have 6,000 stores in China by 2022.

Professor Towson argues that the real challenge for Starbucks and Luckin Coffee is not to steal customers from each other, but to expand the consumer base of coffee drinkers. “Increasing consumption in China is the mother of all coffee opportunities,” he says.

Is the Starbucks “boutique” brand enough to keep it in China?

But most consumers do see there being a choice between the two. Despite Luckin Coffee’s homegrown appeal, some remain unconvinced. Jasmine Xie, 23, runs a creative talent and production company in Beijing. She thinks the Starbucks brand is still more “cool” than Luckin Coffee. “We all know Starbucks coffee isn’t great, but the cups have already become a kind of fashion accessory,” she says. “It’s cool to walk around with a cup of Starbucks; we also spot it in street-style shots of celebrities, models, fashionable people.”

Ms Xie appreciates the atmosphere of Starbucks’ drink-in branches. “The [Starbucks] store feels almost like home and you know the quality of the space is going to be good,” she says.

While drink-in café culture lags behind ecommerce in coffee retail, there is a growing taste for boutique destinations, especially in China’s metropolitan hubs. Starbucks opened its biggest branch in the world, styled as an artisan roastery, in Shanghai in late-2017.

Luckin Coffee could lose out by not being eco-friendly

But there has been some fallout from ecommerce’s seemingly inexorable rise in China’s food and beverage sector in its impact on the environment. According to The Economist, 65 million meal containers are discarded every day in China. A Luckin Coffee delivery comes with at least two layers of disposable packaging, whereas Starbucks sells reusable coffee cups. There is also the resource cost of sending deliverymen on mopeds around the city to deliver single coffees to thirsty customers.

Ms Zhang is among those who believe there should be a system of recycling the packaging. “It is a common problem with all kuaidi [delivery] services,” she says. “On the one hand, you have to make your products look nice and professional, but on the other, it’s hard to keep it environmentally friendly.”

China is still a relatively coffee-light nation. Per capita consumption averages only three cups a year, compared with 250 cups in the UK and 363 cups in America. However, it is a market that is rapidly expanding; it has grown eight times faster than the world average, according to the International Coffee Organisation. With millennials accounting for 40 per cent of coffee-drinking, there are no signs of the taste for caffeine abating, and for most retailers environmental concerns will be secondary to cashing in on this golden opportunity.

Luckin Coffee challenging with low prices, easy takeaway and bulk offers

Starbucks may suffer from US-China trade war