Content creators, whatever their medium, should be wary of middlemen. Any entity producing something that consumers want to read, hear or watch should consider carefully whether it needs a third party to disseminate that material, as it may be better off performing that task itself.

Among other things, the absence of an intermediary enables a producer to retain control of the distribution process and develop a direct relationship with its target audience. This way, it can better understand the preferences of its customers through data-gathering and ensure that any messages it sends them won’t be diluted or misinterpreted.

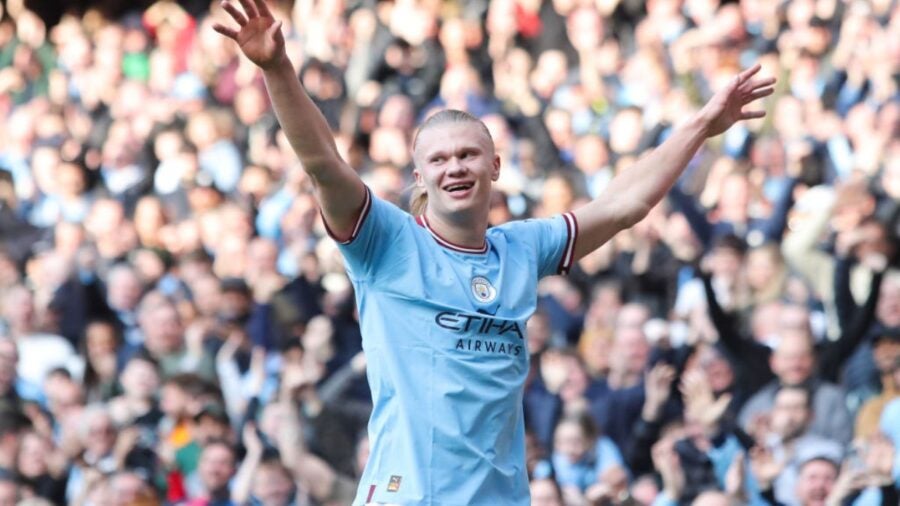

Premier League football is doubtlessly coveted content. It is the world’s most widely watched sporting competition, with 188 of the 193 sovereign states recognised by the UN offering coverage as of 2019. Broadcasting deals in many of these countries are worth billions of pounds.

Yet in the UK, multi-year TV contracts have translated to a premium-priced product that has, according to some observers, been underperforming. In a market where customisation is king and consumers are voting with their wallets, is there scope for something better to take its place?

The piracy problem

Illegal streaming has long been a thorn in the Premier League lion’s paw. It’s not hard to see why this is such a problem. Of the 380 matches played each season, only 200 are broadcast live (legally) on British screens. Sky Sports has 128 games, BT Sport has 52 and Amazon Prime has 20. Someone with subscriptions to all three services could pay up to £1,700 a year, depending on the packages they choose, and still only be able to watch fixtures selected by TV executives.

Nearly half of the Premier League’s fixtures are not available to watch live legally in the UK

Overseas viewers of the Premier League can watch every fixture live and even flick between those being played concurrently. But those in the UK must contend with broadcasters’ selection biases towards certain clubs and the so-called Saturday Blackout. This is the long-standing rule, established to protect the gate income of lower-league clubs, that no match kicking off the standard time of 3pm on a Saturday can be televised live.

Financial advisory website Finder.com has estimated that 4.5 million people in the UK watched live Premier League action illegally during the 2019-20 season. In the same period, Sky Sports had about 6 million subscribers and Amazon Prime had 15 million users, although it isn’t clear how many of the latter number subscribed specifically to watch football.

The advantages of subscription models

If the Saturday Blackout can be circumvented, the tech already exists for the Premier League to provide what Laura Martin, MD and senior media analyst at investment bank Needham and Company, calls “360-degree content”. This would meet the growing demand among consumers for highly personalised experiences.

She adds that, if the league were able to broadcast live fixtures and offer access to archive footage, that could open the door to a “Netflix-style” product, packaged more affordably to attract an even bigger audience.

For Tien Tzuo, the founder and CEO of payment tech firm Zuora, subscription models are a great way for businesses to generate “predictable revenue and stability, even in a tough economic climate”.

If handled with care, a subscriber relationship can represent ongoing value, adds Kate Hardcastle, an independent business consultant. It can “create a deeper understanding of the brand and, in a world of fickle customers, help to create something more lasting. The user data and modelling provide insights and, because a payment system is already in place, add-ons and sell-ups of new products and services can be added with ease.”

The logistics of ‘Premflix’

A source close to the Premier League, who prefers not to be named, reveals that talk of this prospect has “definitely happened” internally, but there are “many creases that would still need to be ironed out” for it to become a reality.

A subscription model would require a reliable platform on which to host the content, a user-friendly enrolment process and a secure payment system, among other things. The provider would also need a good understanding of the needs and wants of its target audience, the price that most members would be prepared to pay and the likely costs of customer acquisition and retention.

Subscription models can offer predictable revenue and stability

One way to make it work could be to bring on an expert. The Premier League has actually already done this for its international streaming service Premier League Productions (PLP), which is run on it behalf by IMG Media, a US firm. But, as long as the broadcasting deals with Sky, BT and Amazon are renewed and the Saturday Blackout persists, the source believes that there are no immediate plans to develop PLP’s operation in the UK.

“The relationships with the TV companies are pretty entrenched, so that’s the first hurdle,” they say. “Second, the Premier League is ultimately run by its member clubs. If you were to tell them that you want to sell the distribution rights at a lower price, albeit to more people, they would probably throw their hands up in horror.”

Before ‘Premflix’ could ever be rolled out in the UK, the source notes, the league would have to resist increased offers from existing partners that don’t want to lose a key product and also get the 20 clubs on board with the project.

“That could create a free-for-all in which the bigger clubs might declare that they’re going off to sell their streaming rights individually,” they say. “So you might end up with Arsenalflix, Liverpoolflix and so on. To convince them, you’d need to be sure that the subscription uptake would genuinely offer more than what they’re currently receiving.”

The success of Disney+ in a saturated market

While the Premier League may be locked into multi-year broadcasting deals, it’s worth bearing in mind that many people are experiencing “subscription fatigue”. That’s the view of Ben Cicchetti, vice-president of corporate marketing at data collaboration platform InfoSum.

He explains that consumers are becoming more selective about which streaming services they continue using as the cost-of-living crisis wears on, focusing on value for money.

Andrew Kitson is head of telecoms, media and technology industry research at BMI Country Risk & Industry Research, a business owned by Fitch Solutions. He cites Disney+, which is priced at £7.99 a month in the UK (without adverts), as a provider with a smart long-term strategy offering originality, exclusivity and affordability.

“By providing its own streaming platform, Disney takes full control of content monetisation,” Kitson says. “It has withdrawn much of its content from other platforms and linear TV services so that its revenue per price of content is not diluted.”

Disney, he adds, has successfully identified its most popular products and isolated these. In effect, it’s presenting consumers with a stark, albeit still relatively affordable, choice: subscribe or miss out.

In 2022, Disney, when also counting its Hulu and ESPN subsidiaries, officially surpassed Netflix as the world’s most popular video-on-demand provider. It reported 235 million subscribers across its platforms, having launched its first streaming service 12 years after Netflix in 2019.

Why ‘Premflix’ has potential

At the Financial Times’s 2023 Business of Football Summit in February, IMG Media’s president, Adam Kelly, told delegates that live sport was the one thing with the ability to “cut through the very fierce battle for attention” among streaming services.

In the same way that Disney has capitalised on its ownership of brands with massive loyal fanbases, such as Pixar, Marvel and Star Wars, the Premier League has a similar opportunity with its hugely popular product.

Disney has made sure that its revenue per price of content is not diluted

According to the Premier League’s own figures, 40% of the UK’s population (nearly 27 million people) watched live coverage during its 2020-21 season – and that’s just counting those who did so legally.

Also speaking at the FT event, Tom Burrows, executive vice-president for global rights strategy at DAZN Group, a digital sports steamer, suggested that it was time for sports TV coverage to move away from “purely transactional” models. Organisations such as the Premier League, he said, needed to work “collaboratively [with broadcasters]… and grow the value of the market – and that means for consumers, too. It can’t be a one-way system.”

Nick Swimer, who was previously Channel 4’s head of legal before joining law firm Reed Smith as a partner specialising in the media, agrees with this analysis.

“We’ve seen with music and movies in recent years that a well-priced offering can certainly disincentivise the use of pirate streaming sites,” he says. “Naturally, this is a good thing, given that those sites occupy a rather sinister position at the intersection of malware and ad fraud. With very low barriers to entry, they proliferate easily and are generally bad news for users.”

While the Premier League does have weapons it can use to counter piracy, Swimer points out that these aren’t always effective. “Pirates often sit behind layers of tech anonymity and operate outside the UK,” he says. “For instance, one based in Russia would not be targetable via litigation or other enforcement tools.”

Ultimately, if the Premier League wants to be the main beneficiary of its own product, it must take control. On top of all the investment and planning that this would require, it would also entail negotiating an end to the Saturday Blackout. But, if such efforts were to culminate in an effective ‘Premflix’ model, the organisation could achieve the rare balance of profitability and popularity, while also dealing a serious blow to the pirates.

Content creators, whatever their medium, should be wary of middlemen. Any entity producing something that consumers want to read, hear or watch should consider carefully whether it needs a third party to disseminate that material, as it may be better off performing that task itself.

Among other things, the absence of an intermediary enables a producer to retain control of the distribution process and develop a direct relationship with its target audience. This way, it can better understand the preferences of its customers through data-gathering and ensure that any messages it sends them won’t be diluted or misinterpreted.

Premier League football is doubtlessly coveted content. It is the world’s most widely watched sporting competition, with 188 of the 193 sovereign states recognised by the UN offering coverage as of 2019. Broadcasting deals in many of these countries are worth billions of pounds.