A colonial UK and Australia were once firm trading allies. It’s said that in the 1880s, less than 100 years after the British colonised the famed ‘land down under’, the UK was the source of 70% of Australia’s imports and the destination for up to 80% of exports.

The 20th century painted a different picture. Australia, keen to prove its independence, began favouring trade deals with the US and Asia, while the UK gravitated towards its European neighbours.

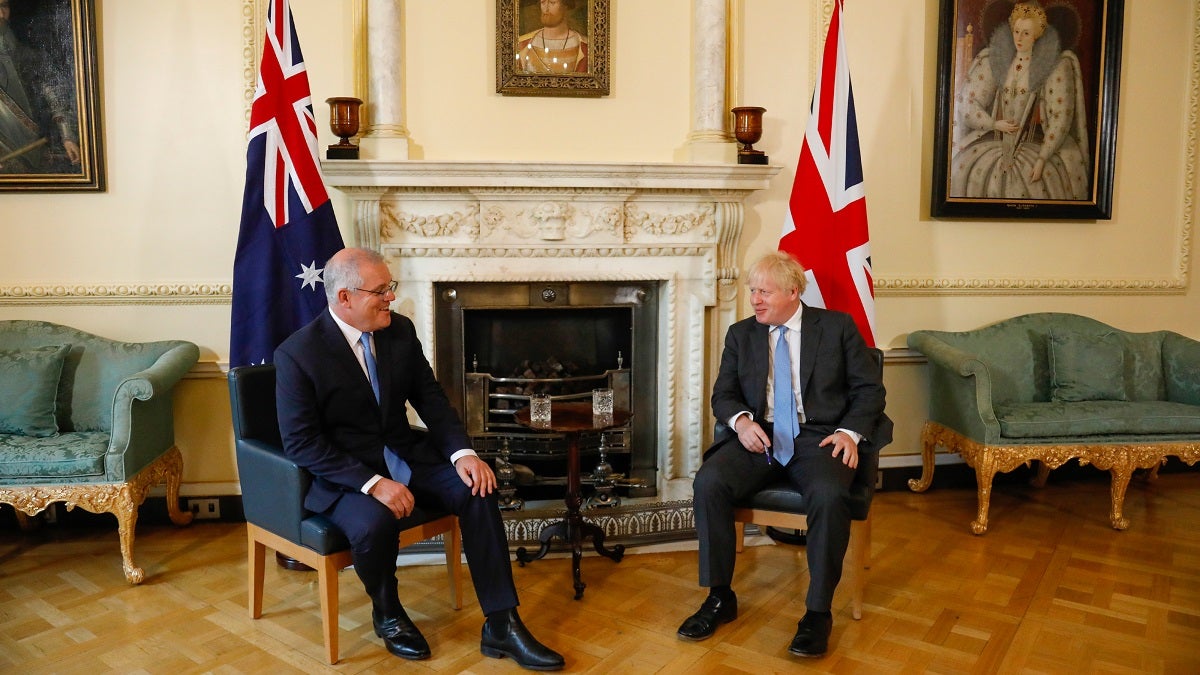

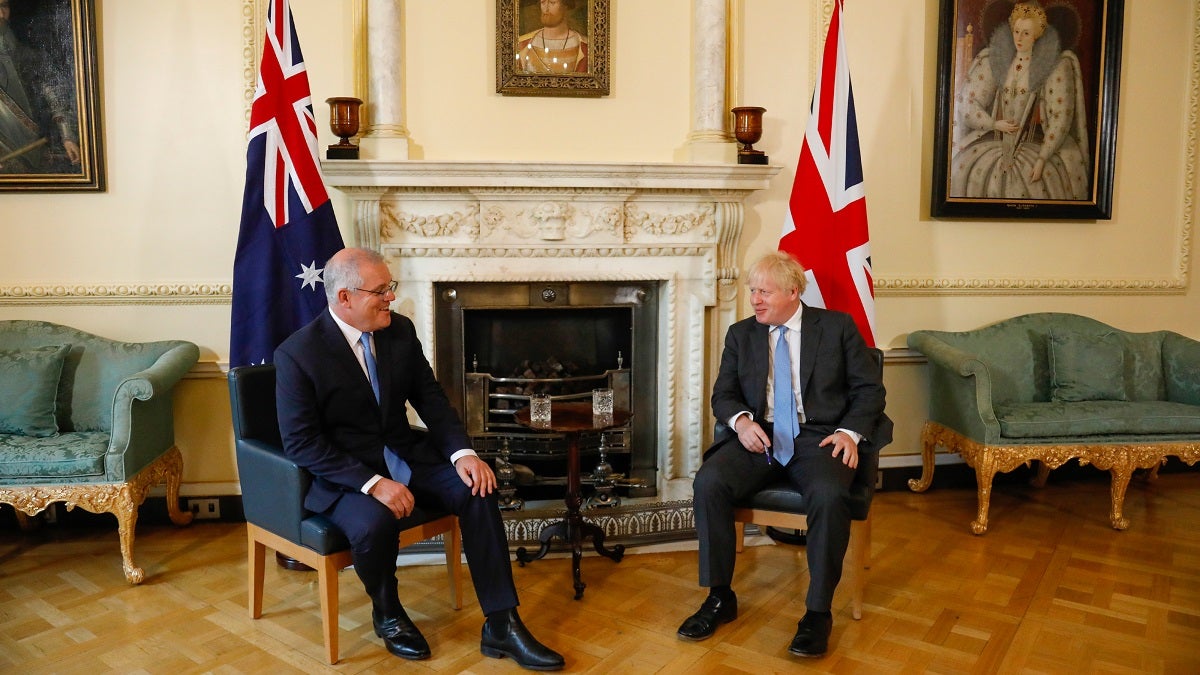

Yet 2021 saw this partnership revived, with the new UK and Australia deal becoming the UK’s first official new free trade agreement (FTA) since exiting the EU. The deal, which is expected to increase UK GDP by 0.08%, ushers Britain into a new post-Brexit era ripe for capitalising on the southern continent’s rich agricultural, mineral and energy resources – not to mention incentivising young Australian workers to help plug the former ‘mother country’s’ talent gap, in a period when job vacancies outnumber candidates.

It also paves the path to forge greater ties with Asia, while setting a precedent for the establishment of more bilateral agreements.

But how do these new opportunities stack up?

Tariffs averaged 2.8% for UK firms importing from Australia and 2.4% for Australian firms importing from the UK before the FTA was agreed, points out Ana Boata, global head of macroeconomic and sector research at Allianz Trade. The FTA removes these, Boata confirms, estimating that UK businesses can expect export gains worth up to £150 million a year.

“Those in the UK’s automotive, machinery and equipment, and agrifood sectors are set to be the biggest winners. Meanwhile, Australian exporters of precious metals and stones – as well as standard metals – are currently accounting for two-thirds of the UK’s imports,” she says.

Yet, before getting ahead of ourselves, Boata adds that the real rewards won’t be reaped until next year, as supply chain bottlenecks are expected to prevail until then.

Bilateral trade agreements can also lead to the homogenisation of standards and regulations that are much needed following the pandemic, says Irina Surdu, associate professor of international business strategy at Warwick Business School.

Many of the problems and delays experienced during the pandemic in industries such as medical device manufacturing and pharmaceuticals, she adds, have been related to red tape, as well as varying policies and legislation in the medical sector. A trade deal with Australia could also help safeguard the UK from the energy crisis spurred by Russian sanctions, by tapping into Australia’s resources.

The world economy increasingly centres on the Pacific region

“So, exchange of knowledge, technologies and expertise is most welcome and would reduce the costs of moving forward in these industries,” she says.

With the UK experiencing labour shortages in highly skilled industries such as financial services and technology, Australian talent could more easily plug the gap under the new FTA, Boata suggests.

Jonathan Beech, managing director at immigration law firm Migrate UK, outlines some of the new reciprocal options.

Australians on the Working Holiday Makers programme will have expanded rights and will be able to stay in the UK for up to three years with an increased cut-off age of 35, and vice versa for UK nationals going to Australia.

Also on the table are more straightforward sponsorship requirements, with UK companies able to sponsor Australian professionals under certain visas, without needing to prove that a UK national could have been hired instead. Professional qualifications will be better recognised across each market, with increased collaboration between accreditation and regulatory bodies.

Meanwhile, Australians interested in undertaking work in agriculture and agribusiness in the UK will benefit from more visa pathways.

“With the lack of restrictions and easy application process, plus potential to switch into a longer-term immigration status, the proposals look attractive,” Beech says.

Perhaps the most lucrative opportunity that the FTA between the two countries opens is the door for the UK to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Made up of Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore and Vietnam, it’s 10 additional markets for UK exporters to target.

The appeal is evident: according to McKinsey, Asia as a whole is forecast to account for 52% of the world’s purchasing power by 2040 and is economically currently worth £8.4tn, representing more than 500 million consumers.

The UK government has now reached the second phase of its negotiations to join the bloc, and, once in, with Australia’s support, it means many experts to member states will become tariff-free – a huge boon for UK businesses, Surdu says.

“UK businesses have taken a hit during the pandemic and desperately need to be able to find new market roots for their services. Most notably, the CPTPP has developed a manual for how digital trade should work effectively. This is an important step towards meeting the Global Britain vision that Brexit promised but is yet to deliver on,” she says.

This is tipped to lead to a £460 million uptick in annual export gains for British exporters, Boata estimates, thanks to the move not only increasing demand for UK goods but ensuring UK businesses are in a better position to expand their digital reach into CPTPP markets.

Meanwhile, new membership applications from China, Taiwan and South Korea mean the CPTTP is set to “emerge as an influential forum for the setting of international regulatory standards and rules in areas such as digital trade and cross-border data flows, that are relevant to an increasing amount of global trade,” a statement from multinational law firm Pinsent Masons notes.

Joining the CPTPP “puts the UK at the heart of a dynamic group of countries as the world economy increasingly centres on the Pacific region,” a UK government announcement also acknowledged.

As individual post-Brexit deals with New Zealand and Singapore have quickly followed that with Australia, precedent is being set for more deals of this nature to be negotiated.

It’s in the UK’s interest to do so, Surdu says, as industries such as renewable energy, military and civil technology, computing, artificial intelligence, as well as pharmaceuticals and medical equipment, are seeing a rise in vertical integration (supply chains becoming owned by one parent company) and reshoring, as national security requirements have heightened.

“In this context, trade agreements serve as routes to avoid trade barriers and share knowledge and expertise that may reduce the costs of doing business and growing new industries,” Surdu explains. “As countries seek to build country-specific advantages in certain related industries, such as digital, financial services, more of these bilateral agreements are expected between the UK and other nations.”

Whether the UK-Australia trade partnership has been renewed in light of or despite the two nations’ shared and often controversial history now seems irrelevant. Both countries stand to gain significantly from creating space between the partners they came to rely on in the recent past, forging a new future together.

A colonial UK and Australia were once firm trading allies. It’s said that in the 1880s, less than 100 years after the British colonised the famed ‘land down under’, the UK was the source of 70% of Australia’s imports and the destination for up to 80% of exports.

The 20th century painted a different picture. Australia, keen to prove its independence, began favouring trade deals with the US and Asia, while the UK gravitated towards its European neighbours.

Yet 2021 saw this partnership revived, with the new UK and Australia deal becoming the UK’s first official new free trade agreement (FTA) since exiting the EU. The deal, which is expected to increase UK GDP by 0.08%, ushers Britain into a new post-Brexit era ripe for capitalising on the southern continent’s rich agricultural, mineral and energy resources – not to mention incentivising young Australian workers to help plug the former ‘mother country’s’ talent gap, in a period when job vacancies outnumber candidates.