Your television is broken. You spend hours online and pop in and out of shops browsing for the best deal for a shiny new TV. But during this search it’s unlikely you spend any time thinking about how the product was made – the sourcing of raw components, the robotic and human processes needed for its manufacture, and how it ends up on the shelf or boxed up on your doorstep.

Manufacturing supply chains are complicated processes that have gone global over the last 30 years. The percentage of global manufacturing that takes place in South-East Asia has rocketed from 24 per cent in 1990 to 45 per cent by 2015. In the same time period, manufacturing in Europe has dropped by 16 per cent, according to United Nations data.

A reduction in tariffs and regulations since the Second World War has internationalised supply chain routes, while technology has made processes more sophisticated. Together, this has allowed trade to grow rapidly, economies to flourish and standards of living to increase.

However, the rise of protectionism across the world, notably the UK’s vote to leave the European Union and US President Donald Trump’s pledge to put America first, has brought both economic and political uncertainty. Manufacturers need to rethink production as potentially increased trade tariffs and regulations could spell disaster for global supply chains, and higher prices for end-consumers.

And global supply chains are even more complicated than you may think.

John Glen, economist at the Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply (CIPS), explains: “The notion that a particular part that goes into a car will travel from Germany into the UK and be put into the car isn’t true. In reality, that part will travel from Germany into the UK, then to France and back to the UK, and then to Belgium and back to the UK, before it ends up in the final product. So, it will cross the border multiple times.”

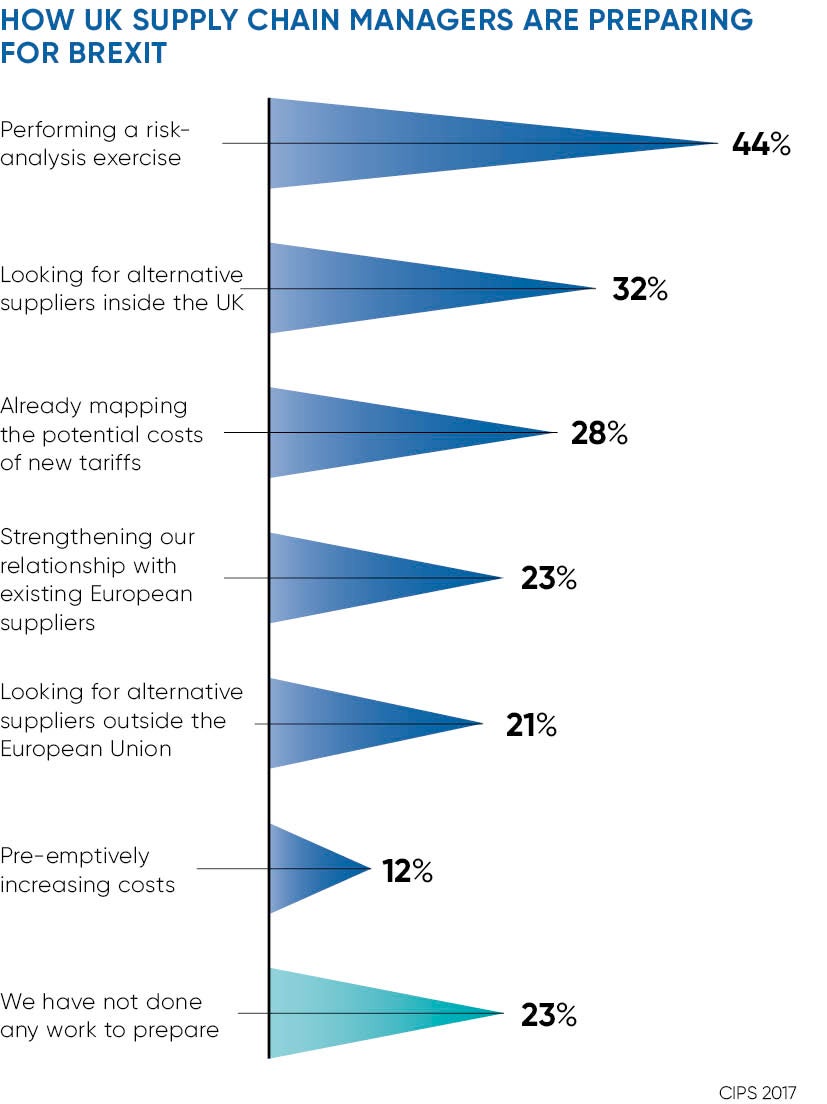

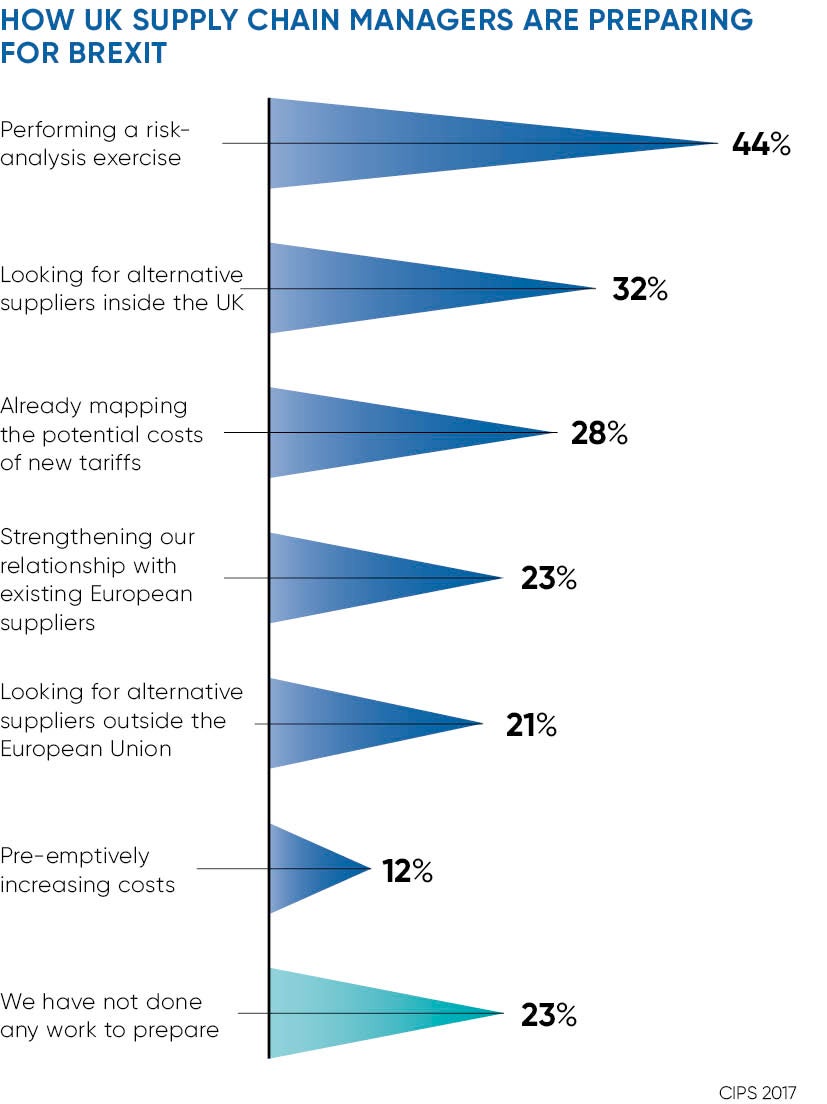

Brexit and a protectionist mandate throw a spanner in the works of supply chains like this. As a result, 32 per cent of UK businesses that use EU suppliers are now looking for British replacements. And it’s happening across the channel too, with 46 per cent of European businesses expecting to reduce their use of UK suppliers post-Brexit, CIPS research has shown.

Looking further afield, Mr Glen points out: “Everyone is holding out for this fabulous trade deal with Donald Trump. Don’t get me wrong, North America is an incredibly important nation for the UK. Approximately 16 per cent of our exports go there. So it’s not an insignificant market, but it will in no way make up for what we lose in Europe. It’s hard to imagine a better free trade deal in North America with a president who has said ‘America first’.”

In the short term, UK manufacturers are still in Brexit limbo. Without knowing the terms of the UK’s exit from the EU, companies can only attempt to be more economical to combat the fall in the value of the pound and work on a scenario basis to begin future planning.

Brexit and a protectionist mandate throw a spanner in the works of supply chains

Rob Williams, founder and logistics director of clothing manufacturer Hawthorn International, explains how his business has changed the way it works with raw materials because of Brexit. “We tried to minimise our losses with Brexit before it happened,” he says.

“A few months before we decided to bulk buy fabric which lasted seven months. However, from January this year we had to repurchase fabrics. Now we try to be more economical in our processes. Now we are paying more for fabric, but getting more items out of each piece to balance out the additional costs.”

Are there any long term gains?

Despite the new economic realities and continuing political uncertainties that in the short term have damaged, and even destroyed, some manufacturers, protectionism may allow these businesses to reap rewards in the longer term.

Many manufacturers hope breaking away from strict EU regulation could boost growth, as the government can help industry invest in innovative technology and support the export of goods. Martin Walder, vice president, industry at Schneider Electric, argues: “The one thing that can happen post-Brexit is that the government can help manufacturers invest in technology. We’re not doing as much as Germany, France and Sweden. That in itself will allow the UK to be more competitive on the global stage.”

On top of improved government support and funding, there are numerous ways for manufactures in the UK and United States to overcome the challenges protectionism presents, from implementing automation to cut money spent on wages, to onshoring previously outsourced suppliers to cut transportation costs and avoid increased border tariffs.

Ben Saunders, client principal at Contino, says: “Trump’s crackdown on H-1B [non-immigrant] visas will encourage ‘American jobs’, which will certainly stifle the influx of technology and engineering experts from low-cost geographies who can add real value. However, recalling that in-house technological capacity is the key to competitiveness, it will allow large organisations to invest in their own people, take ownership of their technology stacks and bring balance to their most-likely ageing workforces, by driving recruitment that focuses on hiring candidates in the 21 to 30 demographic.”

Yet, Jonathan Gibson, associate director at supply chain consultants Crimson & Co, warns: “[Re-onshoring] results in shorter supply chains potentially being more responsive to the local market, but also means that costs are likely to go up, either through the employment of higher priced local labour, or still importing but paying tariffs. The end result of this is likely to be an increased emphasis on automation in the re-onshored factories to try and reduce labour costs.”

Protectionism will also impact exports. Although the pound’s plunge is a good thing for UK exporters, if new trade deals aren’t quickly negotiated post-Brexit, exporters could be hit with high tariffs and tighter regulations.

However, Mr Walder sees this as a good opportunity for UK brands to find new customers in the global market. “The interesting thing is where we head with the broader economies around the world, especially the emerging economies. The size of the middle classes with spending income is growing rapidly in China, India and Indonesia. With that comes demand for consumer goods. UK manufacturers will be looking for the growth opportunities in these economies,” he says.

Yet, despite the opportunities protectionist policies can present in-country manufacturers, the Brexit vote and Trump administration are causing global economic uncertainty and business upheaval. This increases the complexity and cost of global supply chains, a price that will be passed down to consumers.

Will Lovat, vice president, Europe, Middle East and Africa, of supply chain experts LLamasoft, concedes: “There’s inevitably going to be pressure on prices caused by wage inflation and cost inflation of imported raw materials, and people are worried about that.”

Better buy that TV sooner rather than later…