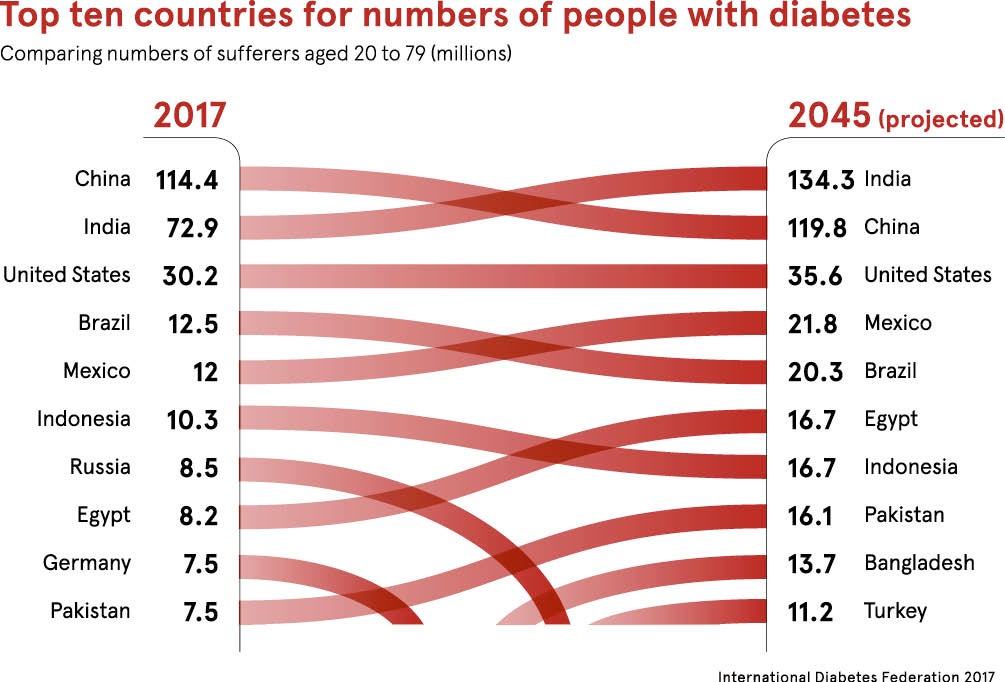

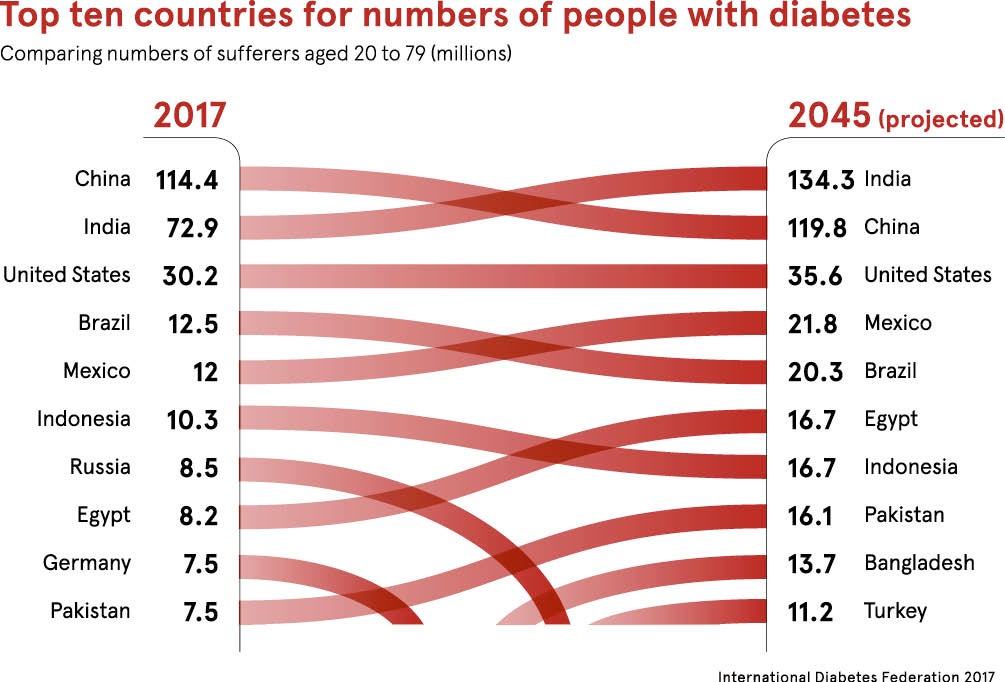

More than 420 million people worldwide have diabetes, four times as many as in 1980, according to the World Health Organization.

But this global figure – equivalent to six times the UK population – masks major difference between countries and regions, both in the prevalence and course of the disease, as well as in the problems associated with it.

Diabetes prevalence has been rising more rapidly in middle and low-income countries, but some poorer countries have much greater numbers of undiagnosed disease than Europe and America.

The scale of type-2 diabetes in south Asia is unprecedented

According to the 2017 Diabetes Atlas by the International Diabetes Federation, the highest diabetes prevalence in adults aged 20 to 79 is in North America and the Caribbean with a rate of 13 per cent, and the lowest in Africa with 3.3 per cent.

But the largest number of people living with diabetes is in the Western Pacific region with 159 million adults affected, making it home to 37 per cent of the total global diabetes population.

Different regions have different health issues

There are also wide regional differences in undiagnosed disease. According to the study, the highest percentage is found in Africa with 69.2 per cent of all cases estimated to be undiagnosed. The Southeast Asia and Western Pacific regions were estimated to have more than 50 per cent of cases undiagnosed, while the lowest proportions of non-diagnosed cases were in North America and the Caribbean (37.6 per cent) and Europe (37.8 per cent).

These differences mean that some areas have specific and unique issues. With south Asians, for example, type-2 diabetes develops at a younger average age and progresses faster than in other ethnic groups. As a result, many complications of the disease are more prevalent and at more advanced stages in south Asian countries than in other regions. This increased incidence adds to the growing burden of the disease putting substantial pressure on poorly developed health systems.

“The scale of type-2 diabetes in south Asia is unprecedented. Urgent attention is required by governments and international agencies to scale up prevention efforts and to provide a basic package of care – metformin, low-cost statins and anti-hypertensive medications – for many people from the point of diagnosis,’” says Professor Anoop Misra at the Centre of Excellence for Diabetes, Metabolic Diseases and Endocrinology, in New Delhi, and lead author of a new paper highlighting the issues in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.

Asia is a particularly problematic area for diabetes

A study from India, cited in the Lancet paper, shows foot examinations were carried out in only 15·1 per cent of patients with type-2 diabetes, compared with more than 90 per cent in high-income countries. The paper also cautions that doctors from south Asia delay insulin therapy and manage people with diabetes less aggressively compared with physicians from other countries.

The problems in Asia as a whole are being tackled in a project set up by Harvard University and the National University of Singapore. The Asian Diabetes Prevention Initiative includes a quick and convenient diabetes risk calculator to give users a personal estimate of their risk of developing type-2 diabetes.

“Much of the information on diabetes prevention on the internet focuses on Western settings, including foods commonly eaten in Western countries,” says Dr Rob van Dam, associate professor and co-editorial director of the project. “Our website takes into account risk profiles, and dietary and lifestyle habits that are common in Asia, and can thus provide more relevant information.”

The widespread cultural practice of walking barefoot can cause major problems in diabetes. Diabetic foot is a complication of diabetes that carries a high morbidity and mortality rate in Africa, and the Diabetes Africa Foot Initiative is aimed at improving care and preventing foot amputations. Health workers from 100 centres have been training in diabetes footcare and a distance learning programme about footcare has been established.

Global focus must be put on prevention

Prevention is a key strategy in most regions. In the United States, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention is working with the American Medical Association to provide doctors with an online toolkit that explains how to identify patients at high risk of developing diabetes, and encourages doctors to refer them to evidence-based prevention programmes in their communities. Those taking part have two goals to lose at least 7 per cent of bodyweight and increase physical activity to at least 150 minutes a week.

While some projects and programmes focus on high-risk groups, such as those of Aboriginal, Hispanic, south-Asian, Asian or African descent, others encourage broad societal changes, with many of them concentrating on diet, which is a key factor in diabetes.

The Outback Stores Initiative in Australia, for example, is designed to help remote indigenous communities to preserve and store fresh fruit and vegetables. The European Commission has also launched a programme to provide young pupils with free fruit and vegetables.

Several countries, have projects focused on reducing intakes of sugar and sweet drinks. According to the UK Treasury, a tax on soft drinks, announced in 2016 and introduced this year, has already resulted in more than half of manufacturers reducing the sugar content of drinks, a drop equivalent to 45 million kilos of sugar a year.

France was one of the first countries to introduce a sugar tax, in 2002, and within six months consumption had dropped by more than 3 per cent.

Different regions have different health issues